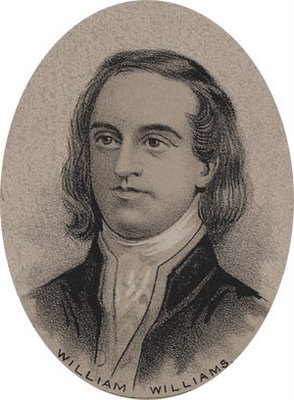

William Williams of Connecticut: Signer of the Declaration of Independence, Pinch Hitting for the United States of America

Rick Miller, playing for Boston Red Sox, holds the 1983 American League record for the highest batting average in a season by a pinch hitter at .45714. Miller, however, is not New England’s greatest pinch hitter.

That title goes to a signer of the Declaration of Independence, the redundantly, patronymically named William Williams. Williams, a successful soldier and merchant of Lebanon, Connecticut, was elected to represent Connecticut on July 11, 1776, seven days after the Continental Congress voted to approve the Declaration of Independence.

Oliver Wolcott had cast the vote on behalf of Connecticut, and Williams’ turn at bat came because the Declaration of Independence, although adopted on July 4, 1776, had to be prepared by clerks and circulated by messenger for signature later. The original Declaration of Independence thus bears William Williams’ name in addition to Oliver Wolcott’s.

Williams came from a good state. Connecticut is known as the Constitution State, and it gets that name due to the “plebesbyterian” genius of the early Puritans. Thomas Hooker, a Puritan contemporary of John Winthrop, Roger Williams, and John Cotton, led the adoption in 1639 of the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut in Hartford as a charter for the Connecticut River towns. The Fundamental Orders were the first charter government that did not refer to the authority of the King of England, but rather to the authority of God through the people.

As Hooker put it – fifty years before John Locke penned his Second Treatise on Government in 1689 – “the foundation of authority is laid, firstly in the free consent of the people … the choice of public magistrates belongs unto the people by God’s own allowance.”

Thus, the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut, animated by Hooker’s thought, anticipated by more than one hundred years the Declaration of Independence, which of course draws its authority from the laws of Nature and Nature’s God, the principle of equality, and the consent of the governed.

Williams came from a good family too, and married into an even better one. Williams was educated at Harvard, graduating in 1751 at age 20. In 1755, Williams volunteered for the militia in the French and Indian War, and served in the Lake George area. Following the war, Williams spent his time in trade and government, rose to prominence, and in 1771, at the age of 40, married 25-year-old Mary Trumbull.

Mary was the daughter of Jonathan Trumbull, also a graduate of Harvard and Governor of Connecticut by royal appointment of the King of England. It is hard to imagine a better-connected New Englander than William Williams of 1771.

The signers of the Declaration of Independence all pledged “our lives, our fortunes and our sacred Honor” to the success of the Revolution. Many paid dearly with the first two, though all in time gained honor. Williams, when he signed the Declaration, had achieved a great deal as a pre-Revolutionary American and had much at stake.

Williams had built and continued to build a record of daring for an established man. He was a member of the Sons of Liberty, a society which fought for the rights of Americans and against British taxation, until it was outlawed by the Stamp Act in 1765. Forced underground, the Sons of Liberty popularized the practice of tarring and feathering for the punishment of officials and loyalists, and were sponsors of the Boston Tea Party.

In 1774, Williams published a pseudonymous letter to the King of England from America, on the subject of the Coercive Act. Williams’ need for a pseudonym is a reminder that a telltale symptom of tyranny is the suppression of speech. In any event, Williams had crossed a line in his letter, accusing the King of England of the most wicked intentions to oppress the American people.

There was never a doubt then, when William Williams got his turn at bat, he would swing for the fences.

William Williams, pinch hitter and American hero, died in Lebanon Connecticut on August 2, 1811.

Eric Wise is an attorney practicing in New York.

Eric Wise is an attorney practicing in New York.

Podcast by Maureen Quinn.

Podcast by Maureen Quinn.

Click Here for Next Essay

Click Here for Previous Essay

Click Here To Sign up for the Daily Essay From Our 2021 90-Day Study: Our Lives, Our Fortunes & Our Sacred Honor

Click Here To View the Schedule of Topics From Our 2021 90-Day Study: Our Lives, Our Fortunes & Our Sacred Honor

Join the discussion! Post your comments below.

Your feedback and insights are welcome.Feel free to contribute!