Guest Essayist: Gary R. Porter

LISTEN ON SOUNDCLOUD:

If it be asked, What is the most sacred duty and the greatest source of our security in a Republic? The answer would be, an inviolable respect for the Constitution and Laws — the first growing out of the last.[1]

Alexander Hamilton goes on to point out that: “The instruments by which [government] must act are either the AUTHORITY of the laws or FORCE. If the first be destroyed, the last must be substituted; and where this becomes the ordinary instrument of government there is an end to liberty!”[2]Where there is no respect for the law, where it has no authority, liberty ends — slavery begins.

“A Republic, if you can keep it,” cautioned Mr. Franklin. A key ingredient of this “keeping,” if Hamilton is to be believed, must certainly be a uniform respect for and obedience of the law. Said another way: the Rule of Law is the bedrock of our society.

But what does “Rule of Law” really mean? Would we know it when we saw it operating? Wikipedia answers: “The rule of law is the principle that law should govern a nation, as opposed to being governed by decisions of individual government officials.”[3]

“[A] government of laws, and not of men,” is how John Adams put it.[4] But the phrase “Rule of Law” presumes we understand what law itself is. Do we?

“…[L]aw and liberty cannot rationally become the objects of our love” (or our respect, we might add) “unless they first become the objects of our knowledge,” states Founder James Wilson of Pennsylvania.[5] So as we begin this discussion of “The Meaning of the Rule of Law and its importance to the functions of Congress in representing the American people,” we should first examine what “law” itself is; what does it encompass? The answer is not as simple as some might suppose.

Noah Webster provides this founding-era definition of law: “A rule, particularly an established or permanent rule, prescribed by the supreme power of a state to its subjects, for regulating their actions, particularly their social actions.”[6] Many authorities point to the Code of Hammurabi (1754 B.C.) as one of the oldest written systems of law, predating even the Ten Commandments (~1513 B.C.), but “Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it,” God’s first oral commandment to man in Genesis 1:28, predates them both.

Even earlier came the Law of Nature. As Sir William Blackstone explains:

“For as God, when he created matter, and endued it with a principle of mobility, established certain rules for the…direction of that motion; so, when he created man, and endued him with freewill to conduct himself in all parts of life, he laid down certain immutable laws of human nature, whereby that freewill is in some degree regulated and restrained, and gave him also the faculty of reason to discover the purport of those laws.”[7]

As Blackstone argues, the Law of Nature should have been discoverable by reason and inquiry. Should have been. But man quickly showed a propensity for “missing it.”[8] God took action.

“[D]ivine providence… in compassion to the frailty, the imperfection, and the blindness of human reason, hath been pleased, at sundry times and in diverse manners, to discover and enforce its laws by an immediate and direct revelation. The doctrines thus delivered we call the revealed or divine law, and they are to be found only in the holy scriptures.”[9] Ergo, the “Laws of Nature and [the Laws of] Nature’s God.”[10] Finally, along came civil laws, such as those of Hammurabi.

So there are three systems of law – natural law, revealed law and civil law — the last deriving its authority from the first. But is all civil law, “good” law? Does it automatically deserve our respect and obedience simply because it has been created by our duly elected representatives? What if in promulgating civil law a conflict is created with natural or revealed law? Frederick Bastiat answers:

“No society can exist unless the laws are respected to a certain degree, but the safest way to make them respected is to make them respectable. When law and morality are in contradiction to each other, the citizen finds himself in the cruel alternative of either losing his moral sense, or of losing his respect for the law—two evils of equal magnitude, between which it would be difficult to choose.”[11]

“Bad laws are the worst sort of tyranny,” said Englishman Edmund Burke.[12] The Roman historian Tacitus expressed a similar sentiment: “Formerly we suffered from crimes. Now we suffer from laws.” “[I]f the public are bound to yield obedience to laws to which they cannot give their approbation, they are slaves to those who make such laws and enforce them,” complained “Candidus” in the Boston Gazette on January 20, 1772. Finally, a civil law which contravenes natural law is either “spoilt law” (Thomas Aquinas)[13] or of “no validity” (Blackstone).[14] Clearly, not all laws are created equal.

Which brings us to Congress. We know from Article 1, Section 1, that the Constitution gives all legislative power to Congress. According to the separation of powers doctrine put forth by Charles-Louis de Secondat, Baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu (the most quoted philosopher of law at the Constitutional Convention), law-making is thus the legitimate purview of neither the Executive nor Judicial branches of government. That’s not the way things work today, but more on that later.

Congress, representing the people, makes laws for the government of the people. But it stands to reason that they should only make laws which reflect the will of the people and which are in the people’s best interest. That also does not always happen today.

Finally, Congress does not have the constitutional authority to make any old laws. According to James Madison, their legislative jurisdiction is (or was) limited “to certain enumerated objects.”[15]

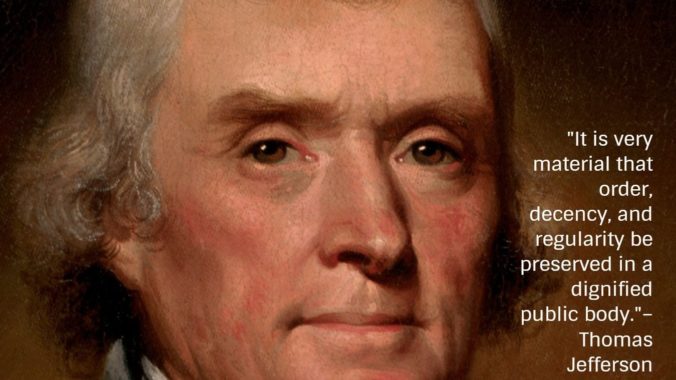

The process by which Congress and the President turn a bill into a law is pretty well-known and will not be repeated here. I should point out, however, that one feature of that process, whereby a bill passed by both houses of Congress automatically becomes law unless vetoed by the President (in all but one circumstance), is a direct result of one of Jefferson’s complaints in the Declaration of Independence: “[The King] has refused his Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good.”[16] Today, we no longer need the assent of the “King” before a “wholesome and necessary” bill becomes law, it does so automatically at the end of ten days,[17] with or without the President’s signature.

Earlier I inferred that all was not well with our law-making process under today’s Constitution. Since that is an integral part of the Rule of Law, let’s take a closer look.

Despite the clear wording of Article 1 Section 1, Congress is today not the exclusive legislative body in the federal government. Executive branch agencies have been given the authority to promulgate “rules” which have the force of law. That they are called “rules” rather than laws is simply cosmetic: if you break a rule you will likely go to jail or be fined just as though you “broke the law.” This improper law-making does not take place in a dark alley somewhere, outside the cognizance of Congress; Congress in fact authorizes it. But this delegation of Congress’ law-making authority runs counter to this principle expressed by John Locke:

“For [the legislative power] being but a delegated Power from the People, they, who have it, cannot pass it over to others. . . . And when the people have said, We will submit to rules, and be govern’d by Laws made by such Men, and in such Forms, no Body else can say other Men shall make Laws for them; nor can the people be bound by any Laws but such as are Enacted by those, whom they have Chosen, and Authorised to make Laws for them.”[18]

This delegation of legislative authority to unelected government bureaucrats was challenged in 1989.[19] The Supreme Court, in an 8-1 decision (Justice Scalia was the lone dissent!), stated:

“… our jurisprudence has been driven by a practical understanding that in our increasingly complex society, replete with ever changing and more technical problems, Congress simply cannot do its job absent an ability to delegate power under broad general directives. Accordingly, this Court has deemed it “constitutionally sufficient” if Congress clearly delineates the general policy, the public agency which is to apply it, and the boundaries of this delegated authority.” (emphasis added)

So Congress passes a skeleton of a law, containing some broad “general policy ,“ and says to the Executive Branch: “fill in the details.”

To guard against the equivalent of President John Adams’ “midnight judges,”[20] Congress gave itself the authority to overturn rules promulgated in the waning days of an outgoing administration; but they must use this authority within a certain “window of opportunity.”[21]

These rules are no small matter. They have bloated the Code of Federal Regulations to more than 175,000 pages and it has been calculated that they add more than $2Trillion to the annual cost of business in America[22] — a cost that is simply passed on to “we the consumer,” a consumer, it should be clear, who is oblivious to this breach of the separation of powers doctrine. Unless the Supreme Court one day overturns Mistretta, Executive Branch law-making is here to stay.

If the Executive Branch can make law, why not the Judiciary? Enter “judge-made law.” “Judge made laws are the legal doctrines established by judicial precedents rather than by a statute. In other words, [the] judge interprets a law in such a way to create a new law. They are also known as case law. Judge made laws are based on the legal principle “stare decisis” which means to stand by that which is decided.”[23] Judge-made law suffers the same defect as delegation to the Executive Branch: law created by other than our elected officials; law created by men and women unaccountable to the people.

“[T]his Court is not a legislature. Whether same-sex marriage is a good idea should be of no concern to us. Under the Constitution, judges have power to say what the law is, not what it should be. The people who ratified the Constitution authorized courts to exercise ‘neither force nor will but merely judgment’….The majority’s decision is an act of will, not legal judgment. The right it announces has no basis in the Constitution or this Court’s precedent.”[24]

Judge-made constitutional law would not be much of an issue if all Justices had a respect for originalism and the intent of the Framers and Ratifiers. Sadly, such Justices are in the minority.

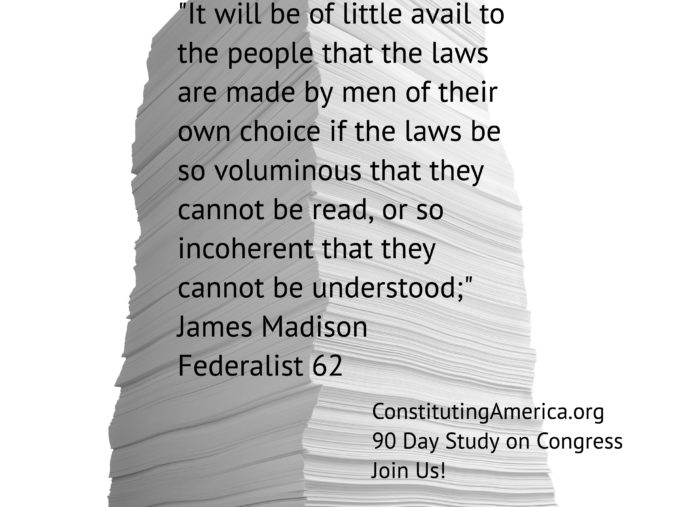

Turning now to whether laws passed by Congress reflect the will of the American people we can point to the example of The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA). The PPACA, nicknamed Obamacare, was passed in 2010 by a Democrat-controlled Congress without a single Republican vote, and was triumphantly signed by President Obama. Public polls of the time consistently showed 60% or more of Americans opposed to the measure yet the 2000+ page bill was rammed through the Congress and became law through an act of pure partisan power. While subsidizing the cost of health care for some Americans who could previously not afford it, the poorly contrived bill, admittedly intended as a step towards a single-payer health-care system, has resulted in higher insurance premiums for most other Americans.

James Madison foresaw this situation:

“It will be of little avail to the people that the laws are made by men of their own choice, if the laws be so voluminous that they cannot be read, or so incoherent that they cannot be understood; if they be repealed or revised before they are promulgated, or undergo such incessant changes that no man who knows what the law is today can guess what is will be tomorrow. Law is defined to be a rule of action; but how can that be a rule, which is little known, and less fixed?”[25]

Gary Porter is Executive Director of the Constitution Leadership Initiative (CLI), a project to promote a better understanding of the U.S. Constitution by the American people. CLI provides seminars on the Constitution, including one for young people utilizing “Our Constitution Rocks” as the text. Gary presents talks on various Constitutional topics, writes a weekly essay: Constitutional Corner which is published on multiple websites, and hosts a weekly radio show: “We the People, the Constitution Matters” on WFYL AM1140. Gary has also begun performing reenactments of James Madison and speaking with public and private school students about Madison’s role in the creation of the Bill of Rights and Constitution. Gary can be reached at gary@constitutionleadership.org, on Facebook or Twitter (@constitutionled).

[1] Alexander Hamilton, “Tully No. 3,” published in the American Daily Advertiser, August 28, 1794, found at https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-17-02-0130.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Found at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rule_of_law.

[4] John Adams, Novanglus No. 7, found at: https://thefederalistpapers.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/The-Novanglus-Essays-by-John-Adams.pdf.

[5] James Wilson, Lectures on Law, 1768, found at: http://www.constitution.org/jwilson/jwilson.htm.

[6] Noah Webster, American Dictionary of the English Language, New York: S. Converse, 1828.

[7] Sir William Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England, 1765, Clarendon Press, Oxford, England. Introduction.

[8] See Genesis 4:8, for starters.

[9] Ibid. Book 1, Chapter 2.

[10] Thomas Jefferson, Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1776.

[11] Frederick Bastiat, The Law, found at https://americanliterature.com/author/frederic-bastiat/book/the-law/.

[12] Speech at Bristol, England, 6 September 1780.

[13] Saint Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, I–II q. 95 a. 2.

[14] Sir William Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England, Book 1, Chapter 2.

[15] James Madison, Federalist No. 14, 1787.

[16] Thomas Jefferson, Declaration of Independence, 1776.

[17] Not counting Sundays.

[18] John Locke, Second Treatise on Government, 1690.

[19] Mistretta v. United States, 488 U.S. 361 (1989).

[20] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Midnight_Judges_Act.

[21] For more on the Congressional Review Act, see: https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R43992.pdf.

[22] See: http://www.nam.org/Data-and-Reports/Cost-of-Federal-Regulations/Federal-Regulation-Executive-Summary.pdf.

[23] https://definitions.uslegal.com/j/judge-made-laws/.

[24] Chief Justice John Roberts’ dissent in Obergefell v. Hodges (2015).

[25] James Madison, Federalist no. 62, February 27, 1788.

Click Here to have the NEWEST essay in this study emailed to your inbox every day at 12:30 pm Eastern!

Click Here for the previous essay.

Click Here for the next essay.

Click Here to view the schedule of topics in our 90 Day Study on Congress.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patrick_Henry#/media/File:Patrick_Henry_Rothermel.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patrick_Henry#/media/File:Patrick_Henry_Rothermel.jpg