LISTEN ON SOUNDCLOUD:

When John Jay, in Federalist No. 2, said he had often noted with pleasure that “Providence has been pleased to give this one connected country to one united people—a people descended from the same ancestors, speaking the same language, professing the same religion, attached to the same principles of government, very similar in their manners and customs, and who, by their joint counsels, arms, and efforts, fighting side by side throughout a long and bloody war, have nobly established general liberty and independence,” he was half right. He recognized that the peoples of the states that declared their independence in 1776 were overwhelmingly Christians and Protestants. Yet he was certainly wrong about them being “one united people,” and about them having a purpose to establish “general liberty and independence,” for as the colonies’ Declaration makes clear, they fought to make each colony, under God, a free and independent state.

The Americans of those colonies had an overwhelmingly Christian background extending through English and Western history to the Old and New Testaments.[1] Their theological background was dominantly Calvinistic, but with diverse expressions. Of the 3,000,000 Americans in 1776 about

900,000 were of Scotch or Scotch-Irish origin, 600,000 were Puritan English, and 400,000 were German or Dutch Reformed. In addition to this the Episcopalians had a Calvinistic confession in their Thirty-nine Articles; and many French Hugenots also came to this Western world. Thus…about two-thirds of the colonial population had been trained in the school of Calvin.[2]

These colonies were the most thoroughly Protestant, Reformed, and Puritan commonwealths in the world. Puritanism provided the moral and religious background of 75 percent of the people who declared their states’ independence in 1776.[3] Ahlstrom says that “If one were to compute such a percentage on the basis of all the German, Swiss, French, Dutch, and Scottish people whose forebears bore the ‘stamp of Geneva’ in some broader sense, 85 or 90 percent would not be an extravagant estimate.”[4]

American culture when our early state constitutions were framed was clearly Protestant, with local variations in each state according to its ethnic, denominational and theological heritages. Education, law, legal thought and legal education were overwhelmingly Protestant—before, during, and long after our first states framed their fundamental laws.[5] These were deeply Christian, with theological presuppositions, philosophies, histories, and precedents reaching back through British and Western history and legal thought beyond the Reformation and the medieval period to the Bible.[6]

Although the peoples of the English colonies were basically one in their commitment to Christianity, the Christian basis of their ethical, political, and legal thought, and their desire to be free of England’s rule, they were not one but many in many other ways. They were many in their theologies, ecclesiastical doctrines, and denominational affiliations. Theologically, they were Calvinists and Arminians, Protestants and Roman Catholics. Denominationally, they were Presbyterians, Congregationalists, Reformed, Episcopalians, Baptists, Methodists, Evangelicals, independents, Lutherans, German Reformed, Dutch Reformed, Hugenots, Quakers, Mennonites. Most were from England, but some were from Scotland, Ireland, Northern Ireland (Scots Irish), France (Hugenots), the Netherlands (Dutch Reformed), or Germany (Reformed, Lutheran, Mennonite). Though most were from England, they spoke different dialects. As Phillips noted in The Cousins’ Wars, those who settled the various colonies were from different parts of England, had fought against each other in the English Civil War (1640s), and would, to some extent, fight against each other again in the colonies’ War for Independence, and later in our misnamed “Civil War”.[7] As was obvious to the colonists, the New England colonies were heirs of the Puritans, quite different from colonists of the more diverse Middle Colonies, and even more different from the more traditional Anglican, Presbyterian and Baptist colonies of the South.

Nor were they one in their economic interests and endeavors. Farming was dominant in every region. But New England’s economy focused on mercantile activity, manufacturing, fishing, and whaling. The Middle Colonies’ focus was on mercantile activity. The South was dominated by agriculture and an agrarian philosophy.

The cultural difference between the people of the North, particularly New England, and of the South was deep. Page characterized it as producing “(t)wo essentially diverse civilizations”,[8] and eventually (1861-1865) our most destructive war. The differences were religious, economic, cultural, and political. Religiously, the South was more Anglican or low-church Episcopalian, Presbyterian, and traditional; the North, especially New England, was Puritan (Calvinistic Congregationalist). Culturally, the South was individualistic, traditional, and conservative; the North was more community-centered, authority-centered, and church-centered. The tyranny of the British king-in-Parliament, not cultural or political convergence, brought the two peoples together for their common defense.[9]

The colonies had different modes of government: in New England the township; in the South the county; in the Middle Colonies a mixture of the two. The New England township was more overtly democratic than the Southern colonies’ governments, but had oligarchic aspects and exercised more power over the individual than Southerners would have tolerated. Southern government was formally more aristocratic, yet substantively much more influenced by the “plain folk” than most historians admit.

The colonies had diverse histories. Each section had been settled by somewhat different groups of people, from different places in England and Western Europe. Though slavery existed in almost all the colonies, it was more successful in the South, so the Southern colonies had larger slave populations, and more diversity in that respect than the other two sections. Peoples of the New England states had more in common with those of the Middle states than they did with the peoples of the Southern states. Moreover, each colony had its own unique history and regional and local differences within its borders.

The relations of the colonies to each other clearly indicate that they were not one people. They were all under the authority of the British Empire, but each was connected to Britain by its own charter. They were not bound only by laws of a common sovereign to them as a whole, for each had its own government. They owed no reciprocal obligations to each other and had no common political interests or duties.[10] As Upshur explains:

The people of one colony owed no allegiance to the government of any other colony, and were not bound by its laws. The colonies had no common legislature, no common treasury, no common military power, no common judicatory….There was no prescribed form by which the colonies could act together, for any purpose whatever; they were not known as “one people” in any one function of government….even in the action of the parent country, in regard to them, they were recognized as separate and distinct. They were established at different times, and each under an authority from the Crown, which applied to itself alone. They were not even alike in their organization. Some were provincial, some proprietary, and some charter governments. Each derived its form of government from the particular instrument establishing it…, without any connection with, or relation to, any other.[11]

The nature and extent of the powers exercised by the Continental Congress did not make the people of all the colonies a “de facto nation” or “one people.” That Congress was not a true civil government: it could only consult, deliberate, pass resolutions, and advise, not legislate.[12]

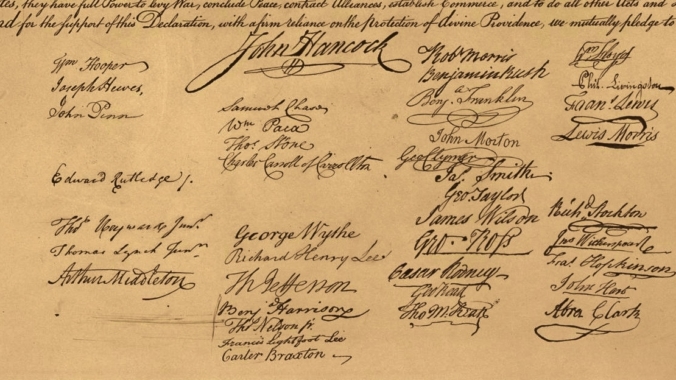

The Declaration of Independence did not “bring forth a new nation”; it brought forth thirteen new independent nations. The Congress that produced that Declaration then acted only upon the authority of the consent and acquiescence of the several states—not upon any authority of a new nation consisting of all the people of the states as a collective entity. It was then a de facto government that, in its ordinary business, relied on the belief that its actions would be approved and confirmed by their states.[13]

In no Continental Congress did the states’ representatives act as representatives of one people. No wonder, for the standard estimate of the loyalties of the colonists is: one-third for independence, one-third against it, and one-third undecided. Every recommendation to send representatives to a general Congress was addressed to the colonies as such, not to “the people.” Each colony acted for itself in the choice of those deputies; none acted in the name of the whole “American people.” The colonies after their Declaration acted as equals, not as areas having a certain percentage of the whole people of a “new nation.”[14] However a state’s representatives were chosen, they were chosen in each particular state for itself alone, certainly not for any “nation.”

The Continental Congress exercised de facto a power of legislation in many cases, but never had that authority de jure by any grant of power from the colonies or from “the people” of “the nation.” Congress’s acts only became valid by the states’ subsequent confirmation. During the course of the war the people

“…never lost sight of the fact that they were citizens of separate colonies, and never, even implicitly, surrendered that character, or acknowledged a different allegiance. In all the acts of Congress, reference was had to the colonies, and never to the people. [Its] measures were adopted by the votes of the colonies as such, and not by the rule of mere numerical majority, which prevails in every legislative assembly of an entire nation.[15]

Acts of the “revolutionary government” were consistent with the independence and sovereignty of the states…. The Continental Congress did not have “exclusive” power to wage war; the independent states used their own sovereign authority to wage their war for independence.[16]

The people of the colonies were not one people before they joined to declare the independence of their states; uniting to form the Declaration did not make them “one people.”[17] The Congress that declared their independence was appointed by each colony separately and distinctly. They deliberated and voted as separate colonies—with only one vote per colony—not in proportion to each colony’s population, as they would have if their collective vote were intended to represent the will of the “national majority.” They did not declare the independence of a new union, but of their thirteen respective states.[18] The delegates signed the Declaration not as random individual representatives of the whole people of the states, but in groups according to their respective states. Foreign countries, in treaties, recognized the distinct sovereignty of the states.[19]

The states’ framing and ratification of the Articles of Confederation did not presuppose or create one people. The Articles’ wording explicitly refutes such an idea: plainly announcing that “each State retains its sovereignty, freedom and independence, and every power, jurisdiction and right, which is not by this confederation expressly delegated to the United States, in Congress assembled.”[20]

Clearly, the states’ framing and ratification of the Constitution did not presuppose one people. Providence gave this geographically united country to the divided peoples of thirteen separate states. Their different colonial histories—in 1776, seven well more than a century, four more than a century, one, more than ninety years, and one, four decades—gave the people of each state a separate identity.

The Constitution did not create one people. It was framed by representatives of the states, whose legislatures chose the delegates they sent to what turned out to be the Constitutional Convention: not by “the people” of the United States as a whole. In Philadelphia each state had only one vote. The states were not allotted votes on the basis of population. They were represented as equals because they were equally free, independent states. The Constitution was ratified by elected representatives of each individual state—the state’s legislature or specially elected ratification convention—not by a popular vote of the people of the state, much less by a national plebiscite.

Each state that ratified the Constitution acted on the basis of its own debates and its own representatives’ decision. In doing so, each state’s representatives determined that the new Constitution and its federal government would not be a threat to its own particular Christian constitution, declaration or bill of rights, governmental system and laws.

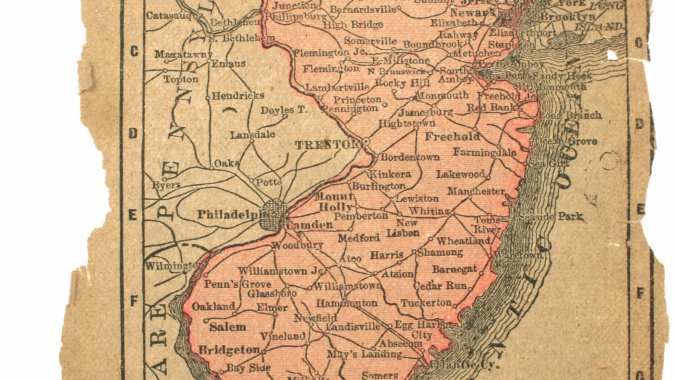

The Christian theory of resistance to tyranny that the colonies followed in resisting the king-in-Parliament continued long after the framing and ratification of the Constitution of the United States (and its Bill of Rights). At least six states—New Hampshire, Maryland, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Massachusetts—stated this right explicitly in their fundamental laws, and thereby implied the right of the people to use all the legitimate means of resistance endorsed by that tradition. Article IV of Maryland‘s Declaration of Rights (1776) phrased it pointedly: “The doctrine of non-resistance, against arbitrary power and oppression, is absurd, slavish, and destructive of the good and happiness of mankind.” Where this doctrine was not stated, it was implicit in the constitutions and declarations of all of the states—which owed their existence to the exercise of precisely such a conviction.

At least three states—Virginia, New York, and Rhode Island—made it plain in their ratification documents that to defend their people’s inherited rights and liberty against central government injustice or tyranny they had the right to secede from the Union established by the Constitution, to take back the powers their people had delegated to the central government whenever it should become “necessary to their happiness.” Some other states’ ratification documents made it clear that each state retains all powers it had not explicitly delegated to the central government, and that these powers remain with each state—as the Tenth Amendment, voicing a common concern of the people of each state, later made explicit.[21] Unquestionably, in God’s providence, the peoples of the respective states intended to remain so.

Archie P. Jones, Ph.D., Teacher, Librarian, Author of The Gateway to Liberty: The Constitutional Power of the Tenth Amendment

[1] Russell Kirk, The Roots of American Order (LaSalle, Illinois: Open Court, 1974), 11-392.

[2] Loraine Boettner, The Reformed Doctrine of Predestination (Philadelphia: Presbyterian and Reformed Publishing Co., [1932] 1972), 382-383.

[3] Sydney E. Ahlstrom, A Religious History of the American People (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday and Co., Image Books, 1975), vol. 1, 169.

[4] Ahlstrom, 169.

[5] Archie P. Jones, “Christianity in the Constitution: The intended meaning of the religion clauses of the First Amendment ” (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Dallas, 1991), 79-144.

[6] Russsell Kirk, The Roots of American Order; Harold J. Berman, Law and Revolution; The Formation of the Western Legal Tradition (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1983); John Eidsmoe, Historical and Theological Foundation of Law, 3 vols., (Powder Springs, Georgia: American Vision Press, Tolle Lege Press, 2012); and Jones, “Christianity in the Constitution,” 145-230.

[7] Phillips has in mind the Puritans who settled New England and the Anglicans who settled the South. Our War Between the States was not a “civil war” because it was not fought for control of the national government but over the right of a state to secede from the union established by the Constitution.

[8] Thomas Nelson Page, The Old South; Essays Social and Political (Chautauqua, New York: The Chautauqua Press, 1919), 259.

[9] Page, 260.

[10] Abel P. Upshur, The Federal Government: Its True Nature and Character; Being a Review of Judge Story’s Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States; With an Introduction and Copious Critical and Explanatory Notes by C. Chauncey Burr (New York: Van Evrie, Horton & Co., 1868). [Reprinted by St. Thomas Press, Houston, Texas, 1977], 35. Upshur’s 242-page point-by-point refutation of Joseph Story’s claim that the Constitution was intended to be based on the national majority will destroys the arguments of multitudes of Fourth of July orations, books, and lectures. It should be required study for any analysis of the Constitution.

[11] Upshur, 36-37.

[12] Upshur, 44-50.

[13] Upshur, 57.

[14] Upshur, 58. The states’ argument in their Declaration of Independence refutes the concept of a binding perpetual union, for the laws of nature and of nature’s God that the Declaration invokes as the standard by which one people is justified in terminating its relationship with another are prior in authority to all unions of peoples.

[15] Upshur, 61.

[16] Upshur, 64, 65.

[17] Upshur, 77, 78.

[18] Upshur, 79-81.

[19] Upshur, 90.

[20] Upshur, 94. This is an obvious forerunner of, and is better worded than the Tenth Amendment.

[21] Archie P. Jones, The Gateway to Liberty: The Constitutional Power of the Tenth Amendment (Powder Springs, Georgia: American Vision Press, 2010), 47-53.

Click Here for the next essay.

Click Here for previous essay.

Click Here to have the NEWEST essay in this study emailed to your inbox every day!

Click Here to view the schedule of topics in our 90 Day Study on Congress.