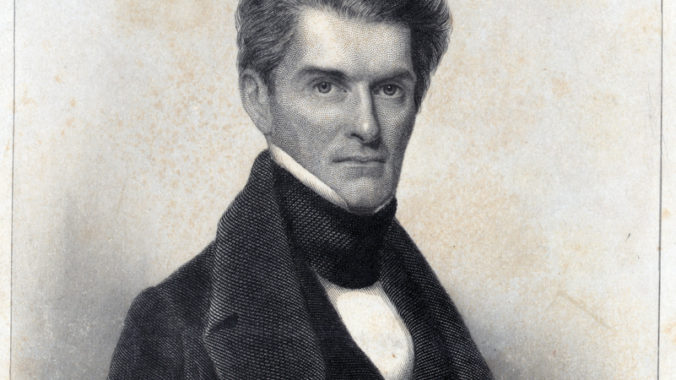

John C. Calhoun (1782-1850) – Seventh U.S. Vice President, South Carolina House & Senate Member, Part 2

LISTEN ON SOUNDCLOUD:

Relying primarily on the Virginia and Kentucky resolutions of 1798 and 1799 against the federal Sedition Act, Calhoun defended the right of a state to interpose itself between its citizens and federal authority and, as Thomas Jefferson had made plain, to nullify the law within its territory. Echoing sentiments that had been expressed by many others since the debates over the ratification of the Constitution, Calhoun posited that the charter was a compact among the states. Addressing the argument that the Constitution had been adopted by the people of the United States, Calhoun pointed out that it had been the people in conventions in their respective states, and that the ratification by the people in one state bound only them. The general government was not a party to the compact, but its creature. Therefore, it could not be the judge of its own powers, whether done through the agency of the Congress, the President, or the Supreme Court. The general government had the character of a joint commission that oversaw and administered the collective interests of the states.

Significantly, Calhoun incorporated the major contribution of 18th century Americans to political theory, the role of the constitutional convention. An act of such foundational character as nullification cannot proceed from mere legislative action. Sovereignty lies in the people, not the government, and an ultimate act of political association or disassociation requires action by them. Since it is not realistic for the people as a whole to gather, such action has to be undertaken by a special body elected and assembled for only that purpose. If the people’s convention votes to nullify the law, the legislature might enact an ordinance of nullification. It is then incumbent on the general government to resolve the conflict peaceably by referring the matter, “as in all similar cases of a contest between one or more of the principals and a joint commission or agency … to the principals themselves,” that is, to a constitutional convention as provided in Article V of the Constitution. If that convention and the subsequent vote of the states supports the nullifying state, fine; if not, that state then, on further reflection, can rescind its nullification or vote to secede from the Union.

It is important to note that a state has no right to secede simply because it changed its mind about belonging to the Union. The Union is more than a contract, it is a political partnership with an existence outside the individual partners. However, if there has been an alteration of the compact, to which the state has not consented, “constitutional secession” is permitted. That was the extent to which Calhoun justified secession. Beyond that lay revolution. As historian Marco Bassani has explained, at that point, “secession would not be impossible, but would amount to a Lockean appeal to Heaven; such cases would arise, not from the nature of the Union, but from the right of self-government of all communities of free human beings. In essence, a ‘pre-political’ right of secession exists, shading over into the right of revolution; there are no significant differences on this point between Webster, Calhoun, Jackson, and the entire American tradition. Institutionalization of power does not eliminate the people’s right to rebel against a despotic government.” Webster himself characterized the address as “the ablest and most plausible, and therefore the most dangerous vindication” of the nullifiers’ argument.

Ultimately, the political application of Calhoun’s nullification theory played itself out in the Henry Clay-crafted compromise over the tariff and the political theater between President Andrew Jackson and the South Carolina state government. The South Carolina convention’s nullification vote over the Tariff of Abominations was followed by Jackson’s threat to use the military to insure compliance with federal law as authorized in the Force Act, which was followed by the convention’s rescission of its tariff nullification after Clay’s compromise, which was followed by its nullification of the Force Act. The tariff issue was allayed, but many understood that to be merely palliation of a symptom, not cure of the ailment. Jackson wrote that the real issue was disunion and that the next symptom would be the struggle over slavery. Calhoun, the moderate, and Rhett, the fire-eater, concurred.

After service as Senator from 1832 to 1844, an abortive campaign for President in 1844, and an interlude as Secretary of State from 1844 to 1845, Calhoun returned to the Senate from 1845 until his death in 1850. He devoted considerable time to further systematic development of his political theory in the Disquisition on Government and the Discourse on the Constitution and Government of the United States. As other political theorists had done, Plato and Cicero coming to mind, Calhoun delved into theoretical exploration of the nature of man and society in the former and into more concrete and empirical application of his theory to American political experience in the latter.

As death approached, Calhoun roused himself once more to a defense of his culture and class. He wrote a blistering speech against Henry Clay’s Compromise of 1850 and the admission of California. Too frail to deliver the speech himself, his friend Senator James Mason of Virginia read it for him. The valedictory’s topic was somber and brooding, a rhetorical reflection of Calhoun’s physical appearance portrayed in contemporary drawings and photos: The stronger (North) would not be deterred from its subjugation of the minority (South); compromise was no longer possible; secession was in the air. He assured the North, “[W]e shall know what to do, when you reduce the question to submission or resistance.” To a friend, he predicted that disunion would follow within twelve years.

Calhoun died shortly thereafter, on March 31, 1850. Because of his strong defense of slavery–he went so far as to describe it as a positive good–and the historical current of nationalism over the past two centuries, Calhoun’s works have not resonated in public debate. Still, his has been described as the only authentic and systematic American political theory, a sentiment that readers of Senator John Taylor of Caroline’s examination of American agrarian republicanism might challenge. It is fair to say, however, that Calhoun’s approach to consent of the governed, as expressed through concurrent majorities of the whole and of its affected constituent minorities, presents a relevant model for peaceful resolution of fundamental political questions that well preserves both “Liberty and Union” in a large, diverse, and divided country.

An expert on constitutional law, and member of the Southwestern Law School faculty, Professor Joerg W. Knipprath has been interviewed by print and broadcast media on a number of related topics ranging from recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions to presidential succession. He has written opinion pieces and articles on business and securities law as well as constitutional issues, and has focused his more recent research on the effect of judicial review on the evolution of constitutional law. He has also spoken on business law and contemporary constitutional issues before professional and community forums, and serves as a Constituting America Fellow. Read more from Professor Knipprath at: http://www.tokenconservative.com/.

Click Here to have the NEWEST essay in this study emailed to your inbox every day at 12:30 pm Eastern!

Click Here for the previous essay.

Click Here for the next essay.

Click Here to view the schedule of topics in our 90 Day Study on Congress.

Join the discussion! Post your comments below.

Your feedback and insights are welcome.Feel free to contribute!