Happy Birthday, James Madison! March 16, 1751 – Federalist Papers 51 & 53: How The American People Hold Congress Accountable

LISTEN ON SOUNDCLOUD:

Federalist 51 is part of a series of essays in which James Madison addressed the principle of separation of powers and its relation to the preservation of liberty and prevention of tyranny. Federalist 53 discusses the significance of the length of service of the House of Representatives to competent republican government.

In preceding essays, Madison examines various suggested mechanisms by which government might be constrained and liberty preserved. Drawing on the Americans’ experience with the British government as well as their own state governments, he rejects all as insufficient. Thus, formal declarations in state constitutions of the legislative power being vested in the legislature, the executive in a chief officer, and the judicial in the courts, are “a mere demarcation on parchment of the constitutional limits of the several departments” and would not suffice to prevent dangerous concentration of power. That is especially true as those same state constitutions had other provisions that allowed members of the legislative branch to exercise executive power. For similar reasons, a mere formal listing of discrete substantive powers to be exercised by each department would be insufficient, because of the tendency of the legislative branch to rely on its connection to the people and its power of the purse to expand its domain and intrude into the affairs of the other branches.

In his Notes on the state of Virginia, Thomas Jefferson proposed “that whenever any two of the three branches of government shall concur in opinion each by the voices of two thirds of their whole number, that a convention is necessary for altering the constitution or correcting breaches of it [Emphasis as written by Madison in Federalist 49], a convention shall be called for that purpose.” Madison criticizes that proposal as at once too weak to prevent combinations by two branches against the third, and as too politically risky because constitutional conventions are prone to stir up the entire body politic. Recourse to the people through conventions would result in the exercise of passion rather than reason. Madison recognizes that his position as a defender of the new constitution and as a member of the convention that had brought it into existence would leave him open to charges of hypocrisy for these remarks. Accordingly, he demurs, “Notwithstanding the success which has attended the revisions of our established forms of government…the experiments are of too ticklish a nature to be unnecessarily multiplied.”

The solution, then, was to “[contrive] the interior structure of the government, as that its several constituent parts may, by their mutual relations, be the means of keeping each other in their proper places.” This required both assuring the independence of each branch from usurpations by the others (separation) and tying them together in exercising the powers of government (blending and overlapping of functions). Further support lay in the division of power in the “compound republic of America…between two distinct governments,” federal and state.

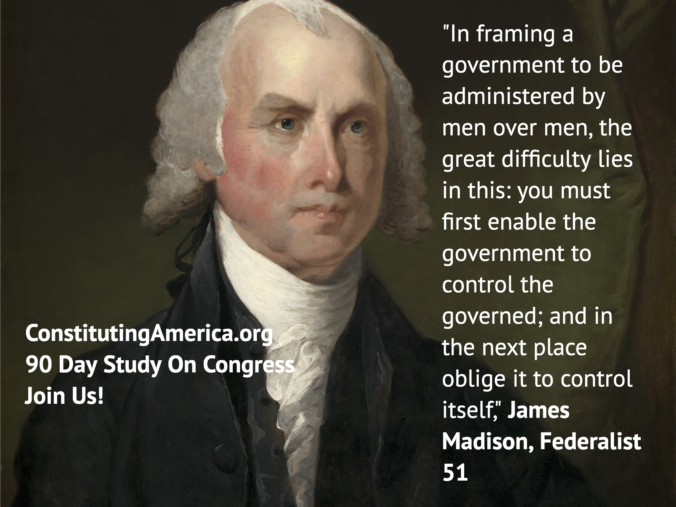

Most important, the structure must harness human nature, especially that of homo politicus, to the task. In the most famous passage of Federalist 51, Madison declares:

Ambition must be made to counteract ambition. The interest of the man must be connected with the constitutional rights of the place. It may be a reflection on human nature that such devices should be necessary to control the abuses of government. But what is government itself, but the greatest of all reflections on human nature? If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary. In framing a government to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself. A dependence on the people is, no doubt, the primary control on the government; but experience has taught mankind the necessity of auxiliary precautions.

These “auxiliary precautions” are particularly needed in a republic, due to what the Framers saw as the inevitable predominance of the legislative branch. Thus, Congress had to be divided. While the chambers have a common function of legislating, they must be elected differently–the House by the people, the Senate by the state legislatures–and operate under different principles, presumably based on the smaller number and longer terms of Senators versus Representatives.

The rest of the essay concerns itself with an issue already thoroughly explored in Federalist 10, the problem of an entrenched majority faction that tyrannizes a defenseless minority. Madison explains that there are only two ways to prevent this evil. One is to “[create] a will in the community independent of the majority.” By that, he means a hereditary system, which he rejects. The other method to prevent factional domination is “by comprehending in the society so many separate descriptions of citizens, as will render an unjust combination of a majority of the whole very improbable.” The requisite diversity of interest groups and the beneficial instability and impermanence of their self-interests is more manifest in the large United States than in its smaller component states and districts.

Running through Madison’s discussion is a questioning of the classic republican faith in a virtuous people selecting virtuous rulers and of the assumption that republics can only work as long as the people retain that virtue. His skepticism reflects the classic liberal approach rooted in 18th century pragmatism that private vices and interests motivate human action, and that it is best “to divide and arrange the several offices in such a manner as that each may be a check on the other; that the private interest of every individual may be a centinel over the public rights.” A virtuous people and, more pointedly, virtuous rulers, are to be welcomed and fostered, but reliance on virtue is neither necessary nor sufficient to guarantee the success of the American experiment. For the republic to endure requires the new constitution’s Newtonian machinery of separated, yet blended, powers.

Not all were convinced. As with other essays of The Federalist, Madison was responding to critics of the new constitution, who saw the document as the product of a self-appointed aristocratic elite that threatened republican self-government. One such attack was a pamphlet by the pseudonymous Aristocrotis. In a slashing and sarcastic tone, its writer assumes the persona of an aristocratic “defender” of the constitution, but one who lampoons the balancing of powers in the Constitution as a contrivance made devoid of substance by the document’s oligarchic artifices. He begins with a back-handed endorsement of the “self-evident truth” that there are those who by nature are designed to rule (such as Thomas Jefferson’s “natural aristocracy”). Examining the separation of the Congress into two chambers, he finds the Senate “agreeable to nature,” but the House as resting on a “most dangerous power”—election every two years by the people. Fortuitously, however, that power is blunted by “proper checks and balances.” Aristocrotis sees those checks in a rather creative distortion of Congress’s constitutional power over federal elections, which members could use to perpetuate their position and to “exterminate electioneering entirely.”

According to Aristocrotis, another check on the people and self-government is Congress’s power to tax individuals directly, which can be used two-fold. First, taxes laid by states will impede the collection of federal revenues and thus be found unconstitutional under the Supremacy Clause. The states will be “deprived of the means of existence, [and] their pretended sovereignties will gradually linger away.”

Second, the people will have to labor to pay the taxes, which “will make the people attend to their own business, and not be dabbling in politics—things they are entirely ignorant of; nor is it proper they should understand.” If the “refractory plebeians” should refuse, because “(such is the perverseness of their natures)…to comply with what is manifestly for their advantage,” Congress has the power to fund the army to enforce its will.

Finally, in that critic’s view, the House will control the election of the president. Thus, Congress can reward an obedient president with re-election. “[T]hough the congress may not have influence enough to procure him the majority of the votes of the electoral college, yet they will always be able to prevent any other from having such a majority.” Then the process will move to the House for the selection of the president. “The congress having thus disentangled themselves from all popular checks and choices…will certainly command…obedience and submission at home.”

Another political axiom for republicans was that legislators must be responsive to their constituents’ wishes, lest the government become oligarchic. One aspect of this was the length of legislators’ terms. Such term limits (as the Americans then understood the concept) were often set at one year or less. Six-year terms of Senators and two-year terms for the House caused wide-spread concern about accountability to the people.

Madison in Federalist 53 attempts to disarm the critics. He notes that terms for the lower houses of the state legislatures vary greatly, though for most it was one year. To be an effective legislator, though, requires not only honest intention and sound judgment, but knowledge. State legislators deal with local matters, with which they tend to be quite familiar by virtue of residing there. Congress attends to diverse national and international matters. As to those, acquiring proper knowledge requires more time and greater exposure to the experiences of Congress’s other members. To the critics’ objection that delegates under the Articles of Confederation served annual terms, he notes–somewhat disingenuously–that they were re-elected almost as a matter of course.

A related principle was “rotation in office,” what today is called term limits. The Articles of Confederation limited a delegate’s service to no more than three years in any six, yet the new constitution lacked such protection. The Constitution is silent on the point. In a clever, perhaps too-clever-by-half, discussion, Madison argues both in favor of the potential of long legislative service and of biennial elections as a constraint on the dangers from extended service. A few members will, due to their superior talent, be frequently re-elected and be “thoroughly masters of the public business.” On that basis, they might seek to gain advantage for themselves. If the bulk of the body were elected only to annual or shorter terms, those novices would not have the requisite knowledge to resist “fall[ing] into the snares that may be laid for them” by the veterans.

The Articles of Confederation had also recognized the states’ power to recall their delegates. No such safety valve existed under the new plan. A South Carolinian Antifederalist writing under the name Amicus pleaded for an amendment to the Constitution that would allow the citizens to recall those who, “so wise in their own eyes,…would if they could, pursue their own will and inclinations, in opposition to the instructions of their constituents.” Such an amendment would not be forthcoming, however.

In 2010, the New Jersey Supreme Court opined that an attempted recall of Senator Robert Menendez through a provision in the New Jersey state constitution would violate the United States Constitution. Combined with the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in U.S. Term Limits v. Thornton (1995), which found an Arkansas state constitutional term limits provision unconstitutional as applied to the Senate and House of Representatives, these cases leave only the process of regular elections at two- or six-year intervals as the means of popular control. To many today, these terms in office may appear just fine, or even too short for the House, given that politicians have to spend much time campaigning for re-election. To many Americans of the early republic, however, such long terms, the absence of both compelled rotation in office and recall of “unfaithful” representatives, and the modern evolution of the position as a full-time occupation, rather than a “second calling,” would demonstrate the oligarchic nature of the system and the people’s inability to heed Benjamin Franklin’s admonition to keep their republic.

An expert on constitutional law, and member of the Southwestern Law School faculty, Professor Joerg W. Knipprath has been interviewed by print and broadcast media on a number of related topics ranging from recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions to presidential succession. He has written opinion pieces and articles on business and securities law as well as constitutional issues, and has focused his more recent research on the effect of judicial review on the evolution of constitutional law. He has also spoken on business law and contemporary constitutional issues before professional and community forums, and serves as a Constituting America Fellow. Read more from Professor Knipprath at: http://www.tokenconservative.com/.

Click Here to have the NEWEST essay in this study emailed to your inbox every day at 12:30 pm Eastern!

Click Here for the previous essay.

Click Here for the next essay.

Click Here to view the schedule of topics in our 90 Day Study on Congress.

Term limits could be revisited on the basis of “qualifications” of the most numerous branch where a disqualifier may be having served to long. But they could be “rotational term limits” that permits officials to return to office after a recess of a term. Such prospects may then help dissuade lame duck behavior where the elected facing a hard term limit may act contemptuously for no longer having to be accountable to the people and make egregious votes on bills.

And yet another informative, enjoyable, wonderful essay. Booyah!

The “Anti-Rats” assertion that the House would elect the President is not without some historical basis. I’ve read that several of the Framers at the Federal Convention were convinced that a majority of elections of the Executive would fall to the House as the last minute, back room contrivance to have Electors picked by the States to select the President [Electoral College] would fail to garner the requisite votes for a clear selection. [is that one long, ugly sentence or what?] :{(

I agree with Ralph that rotational term limits makes a lot of sense. It forces the rulers to live with the ruled and regain some sense of reality. But also allows the experience of learning to run government to be exploited. No more than 3 consecutive terms by the House and two by the Senate with a minimum one term [2 years for House and 6 for Senate] hiatus before being allowed to serve in the same house. If a Senator does not want to wait they can run for a House seat in two years. Although unlikely, a Senator could run for a House seat if they did not want to wait 6 years. It is possible that a legislator would run for Governor. That could be valuable for both the citizenry and the politician if they ever run for House/Senate again.

They didn’t miss many, but I think the framers missed this one.

PSD