Articles Of Confederation – What The Founders Thought Of The Articles Of Confederation And Why They Did Not Last

LISTEN ON SOUNDCLOUD:

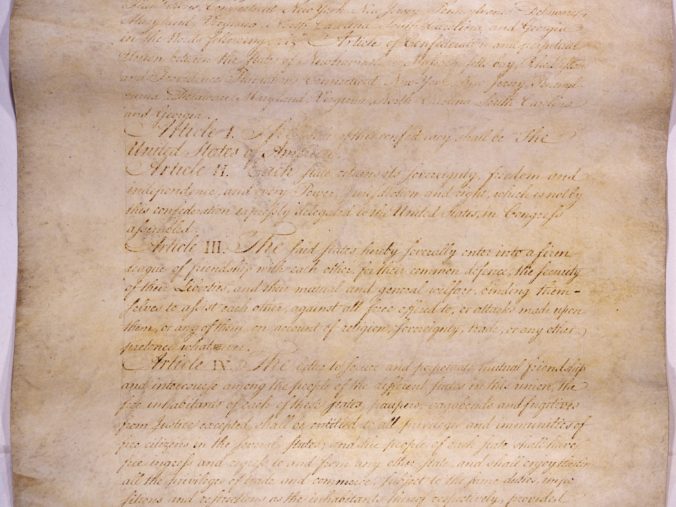

The Articles of Confederation provided America’s first form of government structure, in effect during the years immediately following independence from Britain and ending with the adoption of the U.S. Constitution in 1789. The Articles created a very weak national governing structure, which resembled more of a loose confederation of the different states than a single, unified sovereign entity.

The impetus for this confederation-style of government came in part from the American colonial experience. The Revolutionary War had been driven by the abuses and injustices committed by a distant and tyrannical British government. Colonists equated the centralized power of English rule with the deprivation of their liberties. Therefore, once Americans gained independence, they did not want to risk replicating such an abusive and oppressive central government.

At the same time, Americans trusted their state governments, which had been established under individual state constitutions enacted largely during the Revolutionary period. These state constitutions were highly democratic in form, reflecting as they did the new American enthusiasm for a kind of democracy unknown and unused in the world at that time. This enthusiasm provided another reason that the states were given supremacy in the governing structure of the Articles of Confederation.

Further contributing to the weak and secondary powers given the national government under the Articles was that the states did not want to relinquish their power and autonomy to some central authority. Because the states differed greatly in their interests and identities, they mistrusted how other states might join together through a national government to jeopardize those interests.

The problems and inadequacies of the Articles of Confederation quickly became apparent during its brief tenure. The weak national government proved inadequate to carry out the tasks necessary for it to perform. The Articles essentially allowed the states to go their own way on most issues. The government did not have the power to restrict liberty, but it likewise did not possess the power to unify the states on matters of national interest. Under the Articles, for instance, the government lacked taxing power, struggled to repay the war debt, and had no executive or judicial branches.

Because of these problems and shortcomings, and after the lesson of Shay’s Rebellion, political leaders began debating and designing a new government structure. The resulting U.S. Constitution, implemented in 1789 and in effect today, created a strong national government of three different branches. To supporters, this structure was needed to govern the United States as a nation and not just as a collection of states, each with their own identities and agendas. But a stronger central government also renewed fears of creating the kind of abusive government the colonists had experienced under British rule.

Although the Articles had demonstrated the need for a stronger national government, the primary threat to liberty was seen as emanating from such governments. Therefore, the preeminent debate of the time involved how to limit the new federal government so as to prevent it from having the power to commit the kind of abuses once committed by the British government. Liberty was to be protected by a system of limits on government power, not simply by the absence of government power.

The debate about whether and how the proposed Constitution contained sufficient limitations on the power of the new federal government occupied a central focus of The Federalist Papers, America’s most famous and influential political commentary on the adoption of the Constitution. Such proposed limitations took various forms. The doctrine of enumerated powers meant that the federal government possessed only those powers specifically granted it by the Constitution. This contrasted with the situation of state governments, which under their constitutions possessed all powers not specifically denied them by those constitutions. Other structural limitations on federal power under the Constitution included the doctrines of federalism and separation of powers, which place an array of checks and balances on the ability of each branch and level of government to overstep their boundaries.

Opposition to the Constitution came from the Antifederalists, who did not think the Constitution contained sufficient limits on federal power. The Antifederalists reflected the suspicion of centralized governments that underlay the Articles of Confederation.

Ultimately, the U.S. Constitution was ratified and the Articles of Confederation abandoned, because while liberty was important, so also was the effective governance of the new American nation. Although the Articles gave almost exclusive consideration to preventing central government overreaching, the U.S. Constitution tried to balance the preservation of liberty with the effective governance of a growing nation through a sufficiently strong federal government.

Patrick M. Garry is Professor of Law at the University of South Dakota. http://patrickgarry.com

Click Here to have the NEWEST essay in this study emailed to your inbox every day at 12:30 pm Eastern!

Click Here for the previous essay.

Click Here for the next essay.

Click Here to view the schedule of topics in our 90 Day Study on Congress.

The Antifederalists were emanant from Virginia and called themselves “republicans” (not the GOP). They also called Federalists “monarchists” due to the national engineering dynastic tone of the Federalists who believed in long tenured rulers are best for national vitality. The opposing parties were also known as ratifiers and anti-ratifiers OR rats and anti-rats (a favorite political pun at the time.) Since the Federalists won, historians published the victor’s sentiments as the Federalists and assigned the term Anti-federalist to the republicans.

Ralph, thanks for sharing the rats, anti-rats factoid.