John Quincy Adams (1767-1848) – Sixth U.S. President, Massachusetts House & Senate Member

LISTEN ON SOUNDCLOUD:

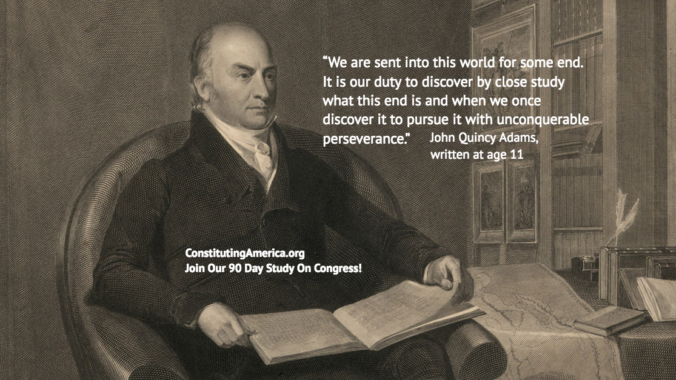

While John Quincy Adams was not an exact contemporary of the Founding Fathers he was, in more ways than one, their offspring. Indeed, his bond with the generation of 1776 was familial as well as philosophical. And his sense of duty to that generation, the project they set in motion, and the preservation of the union they birthed was as deeply embedded in his body as the marrow in his bones. Also in his bones was a strong aversion to party politics, a trait John F. Kennedy would later admire in his book Profiles in Courage. Every action of John Quincy’s life revolved around a higher sense of duty and service to country. A prolific diarist, he wrote, “We are sent into this world for some end. It is our duty to discover by close study what this end is and when we once discover it to pursue it with unconquerable perseverance.”[i] One could understand this sentiment coming from a man like John Quincy, a man who had served his country as a diplomat, ambassador, Congressman, Senator, and President of the United States over the course of a public life spanning over 50 years. But John Quincy wrote these words long before he held any post. He was 11. At that age he found himself crossing oceans with his father in pursuit of independence. From his youth to his old age he would, as he later wrote to his children, “Let the uniform principle” of his “life be how to make your talents and your knowledge the most beneficial to your country and most useful to mankind.”[ii]

Perhaps no one in American history served in so many federal posts. John Quincy was first named Minister to the Netherlands by President George Washington and later as Minister to Prussia (Germany) by his father John Adams when he was President. In both capacities he sought to expand America’s trade and loan relationships and created a broad and effective network of diplomats and influencers he would draw upon in the future.

It was during this time abroad that John Quincy married his wife, Louisa Catherine. They would be together the rest of their lives, enduring multiple miscarriages together, the political fray, and prolonged periods of separation. They did not have the marriage of John and Abigail, but then, perhaps no one could. They would have four children together and John Quincy would push them in the same way he was pushed, encouraging his children to be productive members of society. For some of the children the pressure would be too much. Others would rise to their father’s expectations. All, however, benefited from their parent’s love.

Returning to the states after Thomas Jefferson ascended to the Presidency he entered, albeit with a modicum of foreboding, Massachusetts politics and in short order found himself elected Senator. He had been elected as a Federalist, the party of his father, although he preached the doctrine of independent judgement and country before party. When the time came to vote on Jefferson’s Embargo Act, a measure Federalists vehemently opposed, John Quincy supported it. While he knew the act would hurt Massachusetts industry, he felt it served the country well by keeping it out of a war with England America was ill equipped to fight. This endeared him to no one. The Federalists made their disappointment well known and John Quincy resigned his Senate seat early. He did not back down from his decision, however. He steadfastly proclaimed the ills brought on by partisan loyalties which in his mind too often trumped what was best for the country.

John Quincy, it seemed, was headed for the political wilderness. Taking up a professorship in rhetoric at Harvard he devoted himself utterly to the preparation and presentation of his lectures. But his time in the forests was short lived. A man with his experience, judgement, and lineage would not be on the political bench for too long.

James Madison actually offered John Quincy an appointment to the US Supreme Court, but he declined citing his wife’s heath. Still, Madison kept at it and asked him to become Ambassador to Russia. John Quincy accepted and sojourned to St. Petersburg in hopes of establishing a good relationship with Alexander I. While there the War of 1812 between the Americans and British broke out. The result was that John Quincy found himself paired with Henry Clay and others in Belgium negotiating the Treaty of Ghent in 1814 which brought an end to the war. Because of his work on the treaty John Quincy became Minister to Great Britain, the very same post his father had held years before.

James Monroe would also not serve as President without the tapping into the knowledge, experience, and wisdom he saw exhibited by John Quincy and in 1817 named him Secretary of State. Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and Monroe himself had all served as Secretary of State before going on to become President. The table seemed set for John Quincy.

As Secretary of State John Quincy ushered in an era of almost unprecedented geographic expansion through the Adams-Onis Treaty with Spain which ceded the Floridas to the United States, a joint agreement on the Oregon Territory with Britain, and his clear enunciation of American hegemony in the America’s in what would become known as the Monroe Doctrine.

The Presidency came next. But it would not be achieved with ease. Nor would it be achieved without a deal that essentially doomed any chance John Quincy had of enacting his legislative vision. In addition to John Quincy, contenders for the Presidency in 1824 included Speaker of the House Henry Clay, former Secretary of War John C. Calhoun who would go on to become the spokesman for the South, General Andrew Jackson, and Secretary of the Treasury William Crawford. In the event, none of the candidates received an outright majority and thus the tie had to be broken in the House. While no record of any conversations between John Quincy and Henry Clay survive, Speaker Clay backed him in the House and encouraged others to do the same. A short while later, John Quincy named him Secretary of State. That Clay was qualified for the post did not matter. The politics, however, did. Allegations of a “corrupt bargain” hounded John Quincy throughout his Presidency and destroyed any chance he had of pushing an agenda. John Quincy became the second President in American history up to that point to not win re-election to the highest office in the land. The other had been his father.

Adams seethed but ultimately decided to dedicate the rest of his life to pursuing his love of literature and possibly writing a biography of his father. But this was not to be. For the only time in American history, a former President was headed back into the political arena. Influential members of his Massachusetts congressional district approached him to run for the House of Representatives. Adams agreed.

The story of John Quincy’s House career can be summed up with one word: antislavery. The story of the “gag rule” will be rightly told in another Constituting America essay. Suffice it to say here, however, that Adams had been antislavery his entire life. In Congress his focus on agitating on the slavery question and the Southern response to it served as an opening salvo in what would become the abolitionist movement. While he never became an abolitionist himself he understood the struggle over slavery. Before most others, John Quincy foresaw that conflict was inevitable. In a diary entry in 1820 he wrote,

If the dissolution of the Union must come, let it come from no other cause but this. If slavery be the destined sword in the hand of the destroying angel which is to sever the ties of this Union, the same sword will cut in sunder the bonds of slavery itself. A dissolution of the Union for the cause of slavery would be followed by a servile war in the slave-holding States, combined with a war between the two severed parts of the Union. It seems to me that its result must be the extirpation of slavery from this whole continent; and, calamitous as this course in events in its progress must be, so glorious must be its final issue that, as God shall judge me, I dare not say that that it is not to be desired.

John Quincy served in the House from 1830 to his death, on the floor of the Capitol, in 1848. As William J. Cooper has wonderfully put it, “Adams’ defeat ended one political era and ushered in another. The advent of Andrew Jackson signaled the beginning of a popular politics buttressed by organized, vigorous political parties” which John Quincy had deplored. And perhaps more important, “never again could a presidential contender wear a mantle that had literally been possessed by the Founding Fathers.”[iii] John Quincy’s life had been a testament to what the Founders envisioned and in service to the ideas that emanated from the Revolution they fought so nobly to advance.

Brian Pawlowski is a member of the American Enterprise Institute’s state leadership network and was a Lincoln Fellow at the Claremont Institute for the Study of Statesmanship and Political Philosophy. He has served as a Marine Corps intelligence officer and is currently pursuing a Master’s Degree in American History.

[i] Fred Kaplan, John Quincy Adams: American Visionary (New York: HarperCollins, 2014), 26.

[ii] William Cooper, The Lost Founding Father: John Quincy Adams and the Transformation of American Politics (New York: Liveright Publishing Corp, 2017), 18.

[iii] Ibid. 258.

Click Here to have the NEWEST essay in this study emailed to your inbox every day at 12:30 pm Eastern!

Click Here for the previous essay.

Click Here for the next essay.

Click Here to view the schedule of topics in our 90 Day Study on Congress.

So far, this 90 in 90 study has been fascinating, a true history behind the history lesson, every day. I’ve been sharing most of these and will continue to do so. Thank you again for this great opportunity!

I love this time period of US History. I especially love ready about the lives of Gen. George Washington to Gen. Francis Marion in the South. From Jefferson to Adams, Sumpter to Pickens, Joseph Warren to Sam Adams, and a hundred more. Thank you for sharing these. They make me even more proud to be an American.