Culture Of Debates On The House & Senate Floors

LISTEN ON SOUNDCLOUD:

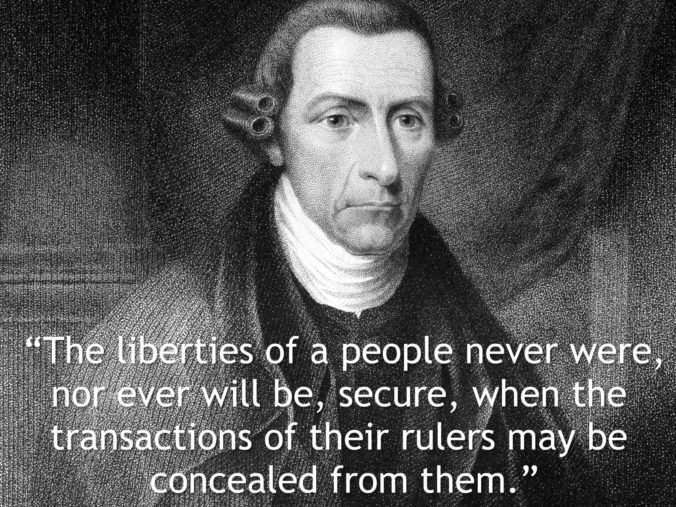

Patrick Henry cautioned, “The liberties of a people never were, nor ever will be, secure, when the transactions of their rulers may be concealed from them.” In their respective chambers, the U.S. Senate and U.S. House of Representatives have developed unique ways to air differences and make sure information is shared. The Legislative Branch’s culture of debate hold’s power accountable and preserves our nation’s civic culture.

The differences between the U.S. Senate and U.S. House of Representatives are very apparent after just watching them for a few minutes.

The U.S. Senate is informal. Senators and staff wander about, mingle, and many conversations are happening at once. Most procedural actions are by unanimous consent. Speeches can go on and on.

The U.S. House of Representatives is very structured. Everything is governed by rules that govern how time is spent, down to minutes. It is the only way 435 voting, and five non-voting, Representatives can balance discourse with action.

Since the first Congress, the differences between the Senate and House have framed important national debates.

The Senate evolved into the chamber for debate. Less people, drawn from the political elite until the 17th Amendment to the Constitution, allowed for greater latitude in allotting time for discussion.

The years 1810 through 1859, were a period known as the “Golden Age” of the Senate. Three of the greatest senators and orators in American history served during this time: Henry Clay (Kentucky) articulating the views and concerns of the West, Daniel Webster (Massachusetts) representing the North, and John C. Calhoun (South Carolina) representing the South.

During these years, these Senate “giants” debated and resolved major issues, holding a divided nation together before the Civil War: the Missouri Compromise of 1820, the nullification debate of 1830 (Haynes-Webster debates), and the Compromise of 1850.

During this “Golden Age” Washington’s elite gathered in the Senate chamber to watch the impassioned oratory and the great compromises take place. The public filled the Senate’s “Ladies’ Gallery” and even sat on couches along the walls of the Senate Floor.

A major step toward supporting this debate culture occurred in 1806, when the Senate dropped using a simple majority to move “Previous Question” to stop debate. The first “filibuster”, from the Dutch term “vrijbuiter” – pirate or pirating the proceedings, happened on March 5, 1841 over the firing of Senate printers. Grinding Senate proceedings to a halt was viewed as an important way to highlight concerns and force a more in-depth consideration of policy.

In 1917, the Senate established “cloture” as a way to limit debate. Initially, cloture required a 2/3 vote. This was changed in 1975 to 3/5, the current 60 votes required.

The House found other ways to expand debate within its strict rules. Members can “revise and extend” their remarks. This means that a one minute speech can become a multi-page discourse in the “Congressional Record”, the permanent and official record of Congressional activities.

On March 19, 1979 the Cable-Satellite Public Affairs Network (C-SPAN) began live broadcast of the House of Representatives. Live coverage of the Senate began on June 2, 1986. Television fundamentally expanded the Congressional audience. Now people, beyond the small public viewing galleries, could watch what happened instead of reading about it.

Republicans embraced the role of television faster and more effectively than the Democrats. They turned the opening one minute speeches into street theater. They used posters and model war planes to create riveting moments highlighting major issues. Republicans also took the obscure device of the “Special Order” to spend hours educating the electorate on issues after official House business ended for the day.

During the first years of C-SPAN Republicans strategically orchestrated their message through an informal group called the Chesapeake Society. This weekly gathering, co-lead by senior legislative staff and Members, developed themes, wrote talking points, and assigned roles for the House’s “Golden Age” of conservative advocacy.

Representatives John Ashbrook (R-OH), Bob Bauman (R-MD), and John Rousselot (R-CA), and their top advisors, collaborated with Phil Crane (R-IL), Bob Dornan (R-CA), Jack Kemp (R-NY), Larry McDonald (R-GA), Don Ritter (R-PA), Gerald Solomon (R-NY), Bob Walker (R-PA), and seventy other Members, to dominate C-SPAN in opposing President Jimmy Carter and House Democrats. Their effective use of the media is credited with helping lay the ground work for the Reagan Revolution.

A second “Golden Age” of House conservatives was led by Newt Gingrich (R-GA) and his Conservative Opportunity Society. They exposed an array of scandals that grew to symbolize the corruption of forty years of Democrat rule in the House. Their most famous use of visuals came on October 1, 1991. Rep. Jim Nussle (R-IA) addressed the House wearing a paper bag over his head. He tore off the bag stating he was ashamed to show his face in the wake of House corruption. These dramatic moments led to the 1994 landslide that propelled Republicans to power for the first time since 1954.

Democrats found their own ways to use the power of the camera. On June 22, 2016, sixty Members staged a sit-in on the House Floor to dramatize the lack of gun control legislation. Republicans turned off the cameras and the lights. Democrats used their cellphone cameras in a social media phenomenon. On February 7, 2018, Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) used her unlimited time prerogative as Minority Leader to turn the usual “house keeping” procedures of the House into an eight hour marathon speech focusing attention on Deferred Action on Childhood Arrivals (DACA).

Formal procedures, precedents, and tradition, linked to ever evolving technology, guarantees that the role of debate remains a viable part of America’s representative democracy in the 21st Century.

Scot Faulkner served as Chief Administrative Officer of the U.S. House of Representatives and as a Member of the Reagan White House Staff. He earned a Master’s Degree in Public Administration from American University, and a Bachelor’s Degree in Government from Lawrence University

Click Here to have the NEWEST essay in this study emailed to your inbox every day at 12:30 pm Eastern!

Click Here for the previous essay.

Click Here for the next essay.

Click Here to view the schedule of topics in our 90 Day Study on Congress.

Thank you for the essay. I learned many new details about how Congress works.

I personally find it very difficult to listen to anyone I do not trust. This speaks as much to my own prejudices as it does to the character of those in office. Perhaps I should try to watch some C-SPAN. Perhaps I will better understand our political leaders. Perhaps I will trust them more. If not, at least then I can say truthfully I listened and weighed them in a balance and found them wanting.

But before I watch any C-SPAN I’m going finish watching NCAA men’s basketball championship game. It is my obligation as a US citizen. :]