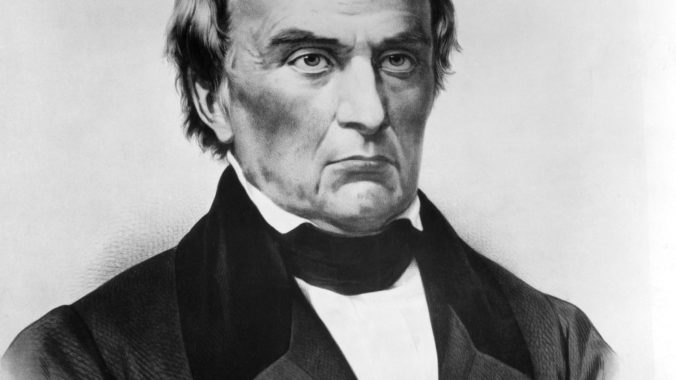

Daniel Webster (1782-1852) – Secretary Of State, New Hampshire House & Senate Member, Known As “The Great Orator,” Part 2

LISTEN ON SOUNDCLOUD:

Webster’s fame as a constitutional lawyer, orator, and political leader was enhanced by his arguments in other cases. In one, Gibbons v. Ogden (1824), Webster represented Thomas Gibbons, who operated a ferry boat under a federal license. Webster argued that Congress had exclusive power over interstate commerce. While Marshall stopped short of Webster’s position, he interpreted the federal power broadly and agreed that Congress could reach the internal commerce of states. Again, as in McCulloch, a state law was found unconstitutional as an infringement on federal power.

In Dartmouth College v. Woodward (1819), Webster represented his alma mater against the attempt by New Hampshire to revoke its charter as a private institution and turn it into a public entity. This time, there was no direct national government interest at stake. Still, Marshall’s opinion, that the state’s action violated the Contracts Clause of the Constitution by impairing the obligations and vested rights under the existing charter, was yet another restriction on state power. Webster’s impassioned advocacy for the protection of rights in property against legislative infringement fit his belief that political participation must be strongly tied to property ownership. Thus, in the Massachusetts constitutional convention of 1820, Webster argued, albeit unsuccessfully, against eliminating property qualifications for voters.

In yet another famous case, Luther v. Borden (1851), Webster represented Luther Borden, a state militia officer who had searched the house of Martin Luther, a leader of an abortive new government for Rhode Island. That state’s colonial charter operated as its constitution even after independence. Due to popular dissatisfaction in the 1840s with the charter’s restrictive property qualifications for voting and the malapportionment of the legislature, a movement under the leadership of Thomas Dorr sought to replace the charter by appeal to the people acting in convention. The movement was initially peaceful, and its new constitution was approved in a popular vote. However, eventually an armed clash occurred between forces allied with the rival “governments,” which the old charter militia won.

The Supreme Court was called on to decide which was the state’s legitimate government. Chief Justice Roger Taney demurred, opining that the Constitution’s command that the United States shall guarantee to each state a republican form of government presented a political question that could not be decided by a court. Of considerable public interest were the two sides’ lengthy arguments. Luther’s attorneys embraced the constitutional view of James Madison and others during the ratification debates over the Constitution that the sovereign people had an unrestricted right to change their constitution at any time, for any reason, and by any (peaceful) means. Webster agreed with this principle as a theoretical proposition only. Ever fearful of revolution, he insisted that such fundamental change could only come through the prescribed means in the state’s constitution or, if none existed, through action by the constituted state government, in this case the old charter government.

His argument in that case paralleled his position against nullification. A single state could not nullify federal law; certainly it could not secede. Therein lay revolution. A dissatisfied state’s recourse against federal power was to follow the procedures set out in the Constitution and persuade the other states to require Congress to call a constitutional convention. There remained, Webster acknowledged, the ultimate right to remove by whatever means a tyrannical government; but this was a right of the American people, not of a particular state government.

Near the end of Webster’s political career occurred yet another spasm in American politics over slavery. In the debate over the Compromise of 1850, crafted by Clay and pushed through the Senate by Stephen Douglas of Illinois, the ailing Calhoun had his speech in opposition to the Compromise read to his colleagues. Three days later, Webster spoke in support of the measure. He began, “I wish to speak today not as a Massachusetts man, nor as a northern man, but as an American ….” He dismissed the very notion of “peaceful secession” advocated by Calhoun. Secession was revolution, and revolution is violent. However, despite his personal opposition to slavery, he criticized the abolitionists and acknowledged the South’s right to have the federal fugitive slave law diligently enforced. This aroused a wave of opposition to him. He resigned his Senate seat within a few months to become, once more, Secretary of State.

During his two-year stint as Secretary of State, he vigorously enforced the new Fugitive Slave Law. His final campaign for President failed at the Whig Party convention. By then, he was also increasingly debilitated from cirrhosis of the liver. He never saw the result of the election, because he died in October, 1852, the immediate cause being head injury suffered from falling off a horse.

Webster’s legacy as a “Union” man is deserved. Still, as a successful politician, his positions changed dramatically over time and, unsurprisingly, tracked the material interests of his constituents. Technological innovations, structural changes in economic relations, settlement of new lands, and the need to assimilate diverse ethnic and religious immigrants all favored development of a national ethos. New England’s and the North’s commercial and industrial rise aligned with that development. Still, Webster’s speeches helped create the political framework for these amorphous forces, and his flair for oratory made this framework intellectually and emotionally accessible to the people. After the nullification debates, in particular, “Union” was no longer defended as just a useful arrangement to assure liberty from foreign domination and to promote harmonious interaction among state sovereignties. It became, instead, the idea of the American republic made real.

There is one more noteworthy point. Despite Webster’s inclination toward political order, his innate conservatism also made him cognizant of human fallibility and skeptical of those who would exercise political power. In a speech in 1837, he issued a warning free citizens must never forget, “There are men, in all ages, who mean to exercise power usefully; but who mean to exercise it. They mean to govern well; but they mean to govern. They promise to be kind masters; but they mean to be masters.”

An expert on constitutional law, and member of the Southwestern Law School faculty, Professor Joerg W. Knipprath has been interviewed by print and broadcast media on a number of related topics ranging from recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions to presidential succession. He has written opinion pieces and articles on business and securities law as well as constitutional issues, and has focused his more recent research on the effect of judicial review on the evolution of constitutional law. He has also spoken on business law and contemporary constitutional issues before professional and community forums, and serves as a Constituting America Fellow. Read more from Professor Knipprath at: http://www.tokenconservative.com/.

Click Here to have the NEWEST essay in this study emailed to your inbox every day at 12:30 pm Eastern!

Click Here for the previous essay.

Click Here for the next essay.

Click Here to view the schedule of topics in our 90 Day Study on Congress.

Although this essay doesn’t involve the 2nd Amendment, I noticed the following statement in the essay: “There remained, Webster acknowledged, the ultimate right to remove by whatever means a tyrannical government; but this was a right of the American people, not of a particular state government.”

It caused me to reread, with a new eye, several documents.

The 2nd Amendment reads “A well-regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.”

The Declaration of Independence reads “it is the right of the people to alter or abolish it (the government).”

The 10th Amendment reads “The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.

So, might the correct argument in favor of the right to bear arms read something like “The PEOPLE retain rights, under the 10th Amendment, that are not delegated to the federal or state governments; one of those rights of the PEOPLE, stated in the Declaration of Independence, is the right of the PEOPLE to alter or abolish the federal government; the 2nd Amendment provides the means for the PEOPLE to both participate in a state militia and also to abolish the federal government; that means is the right of the PEOPLE to keep and bear arms.”

Another greatly appreciated essay. Ron thank you for your research and contribution. The quote at the end of the essay is one of my favorites. Applicable then, now in the future; to governments, businesses, neighborhoods, etc.