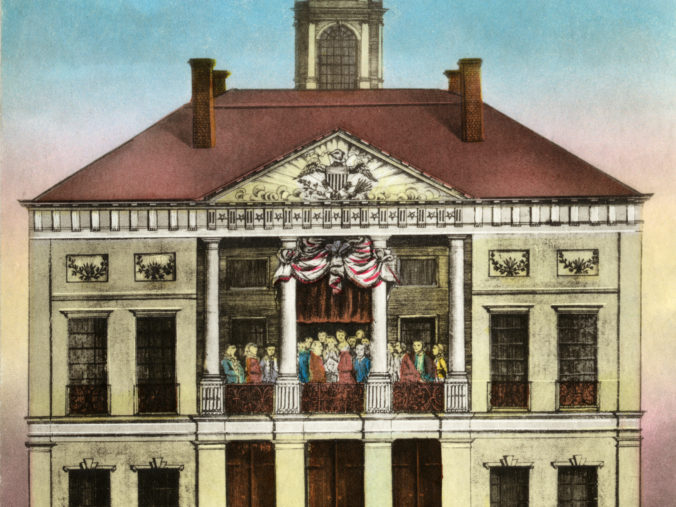

Beginnings Of The United States Congress Part 2 – Guest Essayist: Marc Clauson

LISTEN ON SOUNDCLOUD:

Legislative assemblies came to be debated first in the seventeenth century, especially in England. They were also discussed in theory by Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, James Harrington, and Montesquieu, among others.[1] I will define representation, equating the term with political representation, as “making citizens’ voices, opinions, and perspectives “present” in public deliberation and policy making process” when “political actors speak, advocate, symbolize, and act on behalf of others in the political arena.”[2] When we think of our own American system, we ought to consider the issues the Founders addressed regarding representation, and “built into” the Constitution:

- Why have a legislative body at all, as opposed to a monarch or elected executive?

- Who would be represented by Congress, individuals or states, or both?

- How many “houses” or chambers of a Congress should be created, and why?

- Who would be able to articulate a political “voice” through Congress?

- What powers would this legislative body have, given the inevitable inequality of authority?

- How would the legislative bodies relate to the other branches, Executive and Judicial, the question of separation of powers and checks and balances?

- What should be the “voting rules” (simple majority, super-majority) of Congress for various types of proposed actions?

The Founders had an answer to each of these questions, and in many cases, ingenious answers that were either wholly innovative or combined elements of ideas already existing. The result was a legislative assembly (-ies) that would become the envy and sometimes the object of hatred of other nations and political thinkers and practitioners.

The origins of the American Congress are found in both theory and practice.[3] The issues above were debated at the Constitutional Convention and also in the The Federalist Papers, addressing both the existing “Constitution,” the Articles of Confederation, which established a unicameral Congress, and the proposed new bicameral Congress. An examination of the Founding documents will answer our larger question, why did our Founding Fathers propose the kind of legislative assemblies contained in the Constitution? What was their vision?

To begin, the Founders were avid readers and aware of both philosophical and practical examples of representative political (and ecclesiastical) bodies. They had drawn from many quarters wisdom about law-making and had concluded, similarly to John Locke, that legislation—law making—was best accomplished by a group of decision makers. Since the proposed new government was based moreover on the consent of the people (again, much as John Locke), Congress as conceived should be chosen in some way by the people and represent the people.

Representation entails an inequality of authority as between the electorate and the legislature. But placing all power in one person or one group of persons strikes James Madison as problematic: “The accumulation of all powers, legislative, executive, and judiciary, in the same hands, whether of one, a few, or many, and whether hereditary, self-appointed, or elective, may justly be pronounced the very definition of tyranny.”[4] This statement justifies having a Congress in the theory of separation of powers. Madison also saw this separation as formally dividing law-making from law enforcement. This institutionalization was desirable given the “encroaching spirit of power” in any arrangement.[5] Otherwise, as Montesquieu had said, there could be no liberty.[6] We cannot forget also that the Founders did not hold an overly optimistic view of human nature.[7]

Madison also wrote in Federalist 10, “The federal constitution forms a happy combination in this respect; the great and aggregate interests, being referred to the national, the local and particular to the state legislatures.”[8] Madison is here concerned with federalism, but implicit is the notion that public goods and problems come in “different-sized packages” requiring differing levels of government to address them. The national Congress then can deal with larger issues and, in addition, can represent a large number of people that otherwise could not feasibly be present together in one place at one time through one set of assemblies.[9] This is an advantage of both federalism and republicanism, the latter essentially equivalent to representation by a legislative body.[10]

The Founders however go farther in their analysis. The states and the people as individuals (direct representation) can voice their interests because of the way the Congress is structured. The number of House seats are made to depend on population, while the Senate consists of two delegates per state. The people of larger states can exercise a greater voice in the House, and yet the people have equal representation in the Senate, approximating a “one man, one vote” ideal.[11] Whereas only one method for choosing members and one legislative body would distort political demand, a bicameral legislature provides a balance (as well as a compromise, to be sure).[12] Finally, it adds another check to the internal structure of decision-making, requiring another deliberative body that can slow down or stop undesirable legislation.[13]

A last beneficial aspect of the American Congress has to do with its voting rules. Decisions are of different types, imposing different costs on those to whom a law would apply.[14] Some decisions are “ordinary,” whose social costs are not disproportionate in relation to the problem to be addressed. But others, constitutional-level decisions or extraordinary kinds of decisions, may potentially impose inordinate costs on constituents in relation to the costs of the problem itself. Each of these would require a different voting rule, ranging from simple majority to super-majority. The voting rules for Congress reflect this principle and thereby minimize the potential for costly, even catastrophic, decisions.

No institutional arrangement is perfect, as no individual is perfect. The Founders valued design principles highly, but they also advocated for virtuous public officials. However, they knew they could not guarantee virtue at all times. Therefore, they took pains to design, in this case, a Congress that would give voice to the people while limiting the possible abuses of power in that Congress as well as in the other branches.

Marc A. Clauson is Professor of History, Law and Political Economy and Professor in Honors at Cedarville University. Marc holds a PhD from the University of the Orange Free State, SA, Intellectual History and Polity); JD (West Virginia University College of Law, Jurisprudence); MA, ThM (Liberty University, New Testament Studies and Church History); MA (Marshall University, Political Science); BS (Marshall University, Physics); and PhD work (West Virginia University, Economic Theory).

[1] Bernard M. Manin, The Principles of Representative Government. Cambridge University Press, 1997.

[2] Suzanne Dovi, “Political Representation,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, January 6, 2017, page 1, at https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/political-representation / and Hanna Pitkin, The Concept of Representation. University of California, 1967.

[3] A unicameral Congress already existed under the Articles and had been meeting since before 1776. In addition, the English Parliament was an influential model, especially the House of Commons.

[4] Alexander Hamilton, James Madison and John Jay, The Federalist Papers, edited by George W. Carey and James McClellan. Liberty Fund, 2003, Federalist 47, Gideon edition.

[5] Ibid., Federalist 48.

[6] Ibid., Federalist 47.

[7] See Federalist 10.

[8] Ibid., Federalist 47.

[9] Ibid., Federalist 14, where the representation concept is defended: “Such a fallacy may have been the less perceived, as most of the popular governments of antiquity were of the democratic species; and even in modern Europe, to which we owe the great principle of representation, no example is seen of a government wholly popular, and founded, at the same time, wholly on that principle. If Europe has the merit of discovering this great mechanical power in government, by the simple agency of which, the will of the largest political body may be concentered, and its force directed to any object, which the public good requires; America can claim the merit of making the discovery the basis of unmixed and extensive republics. It is only to be lamented, that any of her citizens should wish to deprive her of the additional merit of displaying its full efficacy in the establishment of the comprehensive system now under her consideration.As the natural limit of a democracy, is that distance from the central point, which will just permit the most remote citizens to assemble as often as their public functions demand, and will include no greater number than can join in those functions: so the natural limit of a republic, is that distance from the centre, which will barely allow the representatives of the people to meet as often as may be necessary for the administration of public affairs. Can it be said, that the limits of the United States exceed this distance? It will not be said by those who recollect, that the Atlantic coast is the longest side of the union; that, during the term of thirteen years, the representatives of the states have been almost continually assembled; and that the members, from the most distant states, are not chargeable with greater intermissions of attendance, than those from the states in the neighbourhood of Congress.”

[10] Ibid., Federalist 10.

[11] See Ibid.,

[12] Ibid., Federalist 52-65 contain an extensive discussion of the House and Senate.

[13] Ibid.,

[14] See James Buchanan and Gordon Tullock, The Calculus of Consent: The Logical Foundations of Constitutional Democracy. University of Michigan 1962.

Click Here for the previous essay.

Click Here for the next essay.

Click Here to view the schedule of topics in our 90 Day Study on Congress.

It is a shame that Amendment 17 was ratified, defeating the entire purpose of the makeup and reasoning behind the composition of the Senate. The States no longer really have the voice that was intended for them.

Emerich de Vattel who wrote The Law of Nations\u> is another source who collectively represents other thinkers in Natural Law, and of course, international law. When the national library burned down, Madison and Jefferson donated their own libraries to reboot the national library and many of these works were instrumental in the debates of the conventions. That library donation list ought to be published as a founder’s era reading list. Public schools have us think that John Lock and Montesquieu were the primary sources for the American Great Experiment. This is on purpose because of the secular nature of the present day education system that is a far cry from the original Common School education system of the 19th century who borrowed much from the originating sources.

Emerich de Vattel who wrote The Law of Nations is another source who collectively represents other thinkers in Natural Law, and of course, international law. When the national library burned down, Madison and Jefferson donated their own libraries to reboot the national library and many of these works were instrumental in the debates of the conventions. That library donation list ought to be published as a founder’s era reading list. Public schools have us think that John Lock and Montesquieu were the primary sources for the American Great Experiment. This is on purpose because of the secular nature of the present day education system that is a far cry from the original Common School education system of the 19th century who borrowed much from the originating sources.