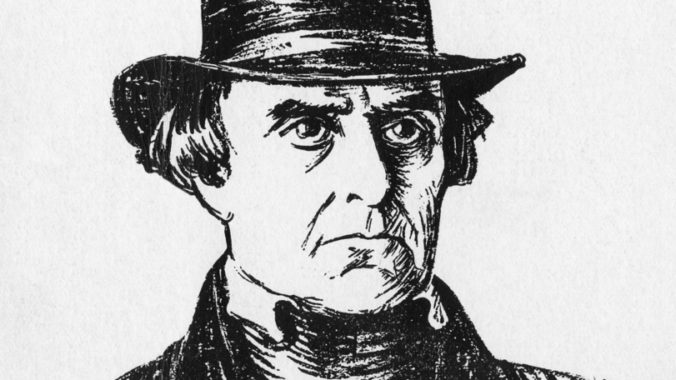

Daniel Webster (1782-1852) – Secretary Of State, New Hampshire House & Senate Member, Known As The “Great Orator”

LISTEN ON SOUNDCLOUD:

Daniel Webster, alongside Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun, was a member of the “Great Triumvirate,” that remarkable group of speakers whose grand and widely-circulated speeches enlivened debates in the Senate and electrified the American people. Webster, the “Great Orator,” in the words of the historian Samuel Eliot Morison, “carried to perfection the dramatic, rotund style of oratory that America then loved.” Webster is primarily known for his role in the Senate during the tumultuous debates over the nullification controversy, the Texas annexation and resulting Mexican War, and the emerging crisis over slavery and the Compromise of 1850. However, he also served as Secretary of State under Presidents William Henry Harrison and John Tyler, and, subsequently, under President Millard Fillmore. He ran unsuccessfully for the Whig Party’s nomination for President in 1836, 1848, and 1852. Of more lasting practical effect even than his Senate speeches were Webster’s numerous appearances as an advocate in great constitutional cases before the Supreme Court.

Webster was born in 1782 in New Hampshire. Through his parents, his education at the Phillips Exeter Academy and Dartmouth College, and his association with the lawyers for whom he clerked, he was steeped in an upbringing that admired Federalist republicanism. That adherence to Federalist principles has often been used to portray Webster as a “nationalist,” a point that he himself used to political advantage, though he called himself a “Union” man. Yet, it is more illuminating to explain Webster as a politician dedicated to the political and economic interests of his section, New England. As those interests changed, so did the political program of the Federalist Party and its eventual successor, the Whigs. And so did Webster. He “evolved” from general skepticism about policies that strengthened national sovereignty against state powers in his tenures in the House of Representatives between 1813 and 1817 (for New Hampshire) and 1823 and 1827 (for Massachusetts) to ringing endorsements of such policies after entering the Senate in 1827. As in a mirror, one sees Webster’s frequent nemesis, Calhoun, move contemporaneously in the opposite direction, from ardent nationalist to foremost theoretician of state sovereignty.

Thus, in 1814, Webster could rail against the abortive proposal by Secretary of War James Monroe to draft 100,000 men to shore up the army during the militarily adverse and financially calamitous War of 1812:

“The operation of measures thus unconstitutional & illegal ought to be prevented, by a resort to other measures which are both constitutional & legal. It will be the solemn duty of the State Government to protect their own authority over their own Militia, & to interpose between their citizens and arbitrary power. These are among the objects for which the State Governments exist; & their highest obligation binds them to the preservation of their own rights & the liberties of their people….Both [my constituents] and myself live under a Constitution which teaches us, that ‘the doctrine of non-resistance against arbitrary power & oppression, is absurd, slavish, & destructive of the good & happiness of mankind.’ With the same earnestness with which I now exhort you to forebear from these measures, I shall exhort them to exercise their unquestionable right of providing for the security of their own liberties.”

This is a far cry from his famous second reply to Senator Robert Hayne in 1830 on the occasion of the “Great Debate” over South Carolina’s nullification of the Tariff of 1828. There, Webster declared, “Liberty and Union, now and forever, one and inseparable!” It was Hayne who on that later occasion appeared to recall the Webster of 1814, with “Liberty—the Constitution—Union.”

Six days after that 1814 speech, the Hartford Convention met. While its final product did not call for immediate secession by New England over the economic difficulties caused by “Mr. Madison’s War,” the topic was discussed and tabled for the future. Webster did not attend that gathering, but had raised secession in his Rockingham Memorial, a remonstrance against the War of 1812 sent to Madison by a state convention of Federalists. The Memorial did not directly urge secession but threatened, “If a separation of the states shall ever take place, it will be on some occasion, when one portion of the country undertakes to control, to regulate and to sacrifice the interest of another.” The Calhoun of the 1830s might have said this with more systematic theoretical grounding, but he would heartily concur with the message.

In similar manner, Webster opposed the tariff of 1816 as being not for the sound and constitutional purpose of raising revenue, but for the improper object of protection of industry. He likewise opposed the tariff of 1824. Yet, by 1828, with the national debt dwindling, he supported the “Tariff of Abominations,” because it protected New England’s textile industry. By 1833, he even opposed Henry Clay’s proposed tariff reduction, because to compromise was to embolden Southerners to threaten nullification and disunion. Perhaps in self-reflection, Webster declared, in another context, “Inconsistencies of opinion, arising from changes of circumstances, are often justifiable.” Calhoun, meanwhile, had supported the 1816 tariff because, he claimed, it was a constitutional revenue measure, not a protectionist one. By 1828, Calhoun opposed the tariff because it hurt the South economically.

The early Webster also opposed Henry Clay’s federally-financed “American System” of internal improvements to develop settlement of the West (which Calhoun initially supported). Once again, by 1828, Webster supported Clay’s plans, with Calhoun now opposed.

One area of great policy dispute during the first half-century of the Republic was the congressional chartering of the Bank of the United States. In contrast to his “flexibility” in other matters, Webster was steadfast regarding the Bank. He was a “sound money man,” who eulogized Alexander Hamilton for his vision about the First Bank, chartered in 1791, and the stability it brought to American finance and the public credit: “He smote the rock of the national resources, and abundant streams of revenue gushed forth. He touched the dead corpse of Public Credit, and it sprung upon its feet.”

To restore that stability after the humbling experience of the War of 1812, Webster supported Calhoun’s initiatives to charter the Second Bank in 1816 and Clay’s move to re-charter it in 1832. He also vigorously opposed Jackson’s anti-Bank policies, not just because they were Jackson’s as much as he feared the economic dangers from irresponsible issuance of paper money by undisciplined local banks. “Of all the contrivances for cheating the laboring classes of mankind, none has been more effective than that which deludes them with paper money,” he charged during the debate on re-chartering the Second Bank. Contemplating the demise of the Second Bank following Jackson’s veto of the re-charter bill, Webster mourned, “We are in danger of being overwhelmed with irredeemable paper, mere paper, representing not gold nor silver; no sir, representing nothing but broken promises, bad faith, bankrupt corporations, cheated creditors and a ruined people.” At times, he was branch director, legal counsel on retainer, and advocate in Congress for the Bank. His penchant for luxurious living beyond his means and his financial speculations and gambling habit caused him to be frequently in debt and led to conflicts of interest, not just with the Bank.

His political support for the Bank was felicitously aligned with his constitutional argument in one of the most significant cases about Congressional power, McCulloch v. Maryland in 1819. Webster represented James McCulloch, the branch cashier (a key officer) of the Bank. The Court held that a state tax on a federally-chartered instrumentality was unconstitutional. In a wide-ranging argument, almost entirely adopted point-for-point by Chief Justice John Marshall, Webster claimed broad federal power to enact laws that were useful or convenient to achieve the objectives expressly delegated to Congress in the Constitution. Webster’s argument tracked Hamilton’s in the debate over the constitutionality of the original Bank. It was startlingly different than the constitutional argument about federal power Webster had made five years earlier in his speech against military conscription, “To talk about the unlimited power of the Government over the means to execute its authority, is to hold a language which is true only in regard to despotism. The tyranny of Arbitrary Government consists as much in its means as in its ends … All the means & instruments which a free Government exercises, as well as the ends & objects which it pursues, are to partake of its own essential character, & to be conformed to its genuine spirit.”

An expert on constitutional law, and member of the Southwestern Law School faculty, Professor Joerg W. Knipprath has been interviewed by print and broadcast media on a number of related topics ranging from recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions to presidential succession. He has written opinion pieces and articles on business and securities law as well as constitutional issues, and has focused his more recent research on the effect of judicial review on the evolution of constitutional law. He has also spoken on business law and contemporary constitutional issues before professional and community forums, and serves as a Constituting America Fellow. Read more from Professor Knipprath at: http://www.tokenconservative.com/.

Click Here to have the NEWEST essay in this study emailed to your inbox every day at 12:30 pm Eastern!

Click Here for the previous essay.

Click Here for the next essay.

Click Here to view the schedule of topics in our 90 Day Study on Congress.

Webster’s mutability comes through clear in reading both essays. I remember clearly in 2007/08 learning was how easily Senator Barack Obama could vacillate from one extreme to the other on an issue.