Guest Essayist: Marc Clauson

LISTEN ON SOUNDCLOUD:

Rule of Law and Congress

The concept of a rule of law has been misunderstood throughout the history of political thought, and often ambiguous.[1] In this essay I will define the concept, trace its development, then apply it to the American situation in its relationship to Congress. In doing so, the fundamental idea of constitutionalism will become crucial to any understanding of an effective rule of law.[2]

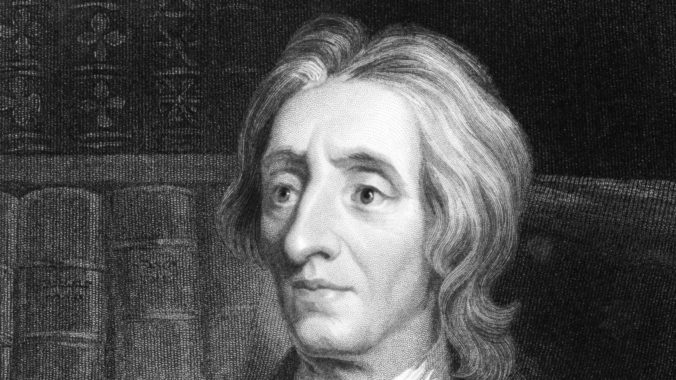

In 1644, the English theologian and political thinker, Samuel Rutherford, published a book entitled Lex, Rex, which translated, means, “Law is King.” The book was written during the English Civil War, which in part was fought over the issue of the power of the king (Charles I) in relation to the Parliament. Charles had asserted his divine right, absolute, authority, though he also recognized a subordinate role for Parliament. In other words, as most monarchs of that time believed, Charles essentially argued that he was above the law, even laws made by Parliament, since he sat in Parliament itself as its chief executive.[3] In fact the dominant theory through most of the seventeenth century was absolute, divine right monarchy. Legislative bodies therefore were at best the “loyal opposition” to monarchs in most cases until the English Civil War (1642-1649). But during that War and again in and after the Glorious Revolution of 1688, the English Parliament came into its own as a force to be reckoned with, even the foremost branch of government, both in practice after 1688 and in theory, for example in John Locke’s Second Treatise of Government (1689).

But the question then remained for the “legislative,” as the powers of a legislative branch were labeled, is there a limit to the power of that branch? Does it operate under a rule of law like a monarch? Here we must define the concept.

One definition runs:

“The most important demand of the Rule of Law is that people in positions of authority should exercise their power within a constraining framework of well-established public norms rather than in an arbitrary, ad hoc, or purely discretionary manner on the basis of their own preferences or ideology. It insists that the government should operate within a framework of law in everything it does, and that it should be accountable through law when there is a suggestion of unauthorized action by those in power.”[4]

The essential idea is that no ruler or governing body is above the law, even those who actually make those laws. The concept does not provide criteria for the content of laws, but it does require every citizen and governing official to abide by those laws if they are a part of the jurisdiction in which the particular laws are effective. Other elements have been suggested to fill out the rule of law idea, including (1) Formal aspects: generality; publicity; prospectivity; intelligibility; consistency; practicability; stability; and congruence. These principles are formal, because they concern the form of the norms that are applied to our conduct; (2) Procedural aspects: impartial hearing, evidence presented, etc.; and (3) Substantive aspects, that is, the actual content of laws is considered part of the rule of law, for example, property rights.[5] Most people would think that the procedural aspects are the heart of the rule of law, that is, the rule of law addresses a “fair procedure” without pre-determining an outcome. In the case of Congress, while procedure is no doubt important, the Constitution itself is also vitally concerned with the content of laws—what Congress may do and, by implication (or directly in the Tenth Amendment), what it may not do. At this point we move into the realm of constitutionalism as an aspect of the rule of law. There are two ways in which the Constitution impinges on rule of law issues:

- By establishing rules for law making itself, that is, decision rules of various types (simple majority, 2/3 majority, etc.). These are important procedural norms designed for differing kinds of decisions that are associated with varying costs to citizens affected and for the laws themselves.[6]

- By ratifying Article Two, which, among other things, enumerates the specific powers of Congress, implying that these are the only powers, and thereby providing a limit to Congress’ powers.[7]

It may also be argued that the entire Constitutional structure implies that any law enacted by Congress also applies to its members and to any government official. After all, a constitution, properly understood, is only alterable by the people and that would imply that it governs all officials as well as citizens generally. Though such wording does not appear in the Constitution, it goes to the very heart of the rule of law. Unfortunately, laws have not always been applied to members of Congress, as evidenced especially in recent years (for example, the Affordable Care Act of 2010). Nevertheless, generally, Congress is bound by its own laws equally with any citizen. Morally, there is no question as to the validity of that assertion. Legally, we may also point to the checks and balances concept which is the constitutional method of enforcing the rule of law on Congress in terms of its powers (though it does not speak to the issue of Congressional self-exemption from laws).

In his Second Treatise of Government, John Locke, in discussing the “legislative” power, clearly states that all laws must be applicable to every citizen, even the rulers.[8] Locke influenced the Founders, even during the constitution phase, though of course he was not the only important source. Not only that, but the Founders were keenly aware of the writings in England that excoriated the corruption of the Parliament in the earlier 1700s and their own day.[9] Finally, the Founders consciously designed a constitution that explicitly limited state power and provided incentives for virtuous behavior. All these, but especially the idea of the rule of law were seen as applicable to Congress itself. Without the concept in actual general practice, citizens would be subject to many abuses by governments simply because the governors would not themselves be subject to those same laws. Given human nature as self-interested at the least, this could lead to an intolerable state, even one of tyranny.[10] To the extent the rule of law is “institutionalized” the possibility of tyranny is minimized.

Marc A. Clauson is Professor of History, Law and Political Economy and Professor in Honors at Cedarville University. Marc holds a PhD from the University of the Orange Free State, SA, Intellectual History and Polity); JD (West Virginia University College of Law, Jurisprudence); MA, ThM (Liberty University, New Testament Studies and Church History); MA (Marshall University, Political Science); BS (Marshall University, Physics); and PhD work (West Virginia University, Economic Theory).

[1] See Brian Tamanaha, On the Rule of Law: History, Politics, Theory. Cambridge University, 2004.

[2] On this topic more generally, see Ellis Sandoz, editor, The Roots of Liberty: Magna Carta, Ancient Constitution, and the Anglo-American Tradition of Rule of Law. Liberty Fund, 1993.

[3] Lex, Rex, or, the Law and the Prince: A Dispute for the Just Prerogative of King and People. Containing the reasons and causes of the most necessary … H. Grotius … In forty-four questions (1644). Sprinkle Publications, 1982. Charles’ father James I had also written about his divine right, absolute monarchy in The True Law of Free Monarchies (1610).

[4] Jeremy Waldron, “The Rule of Law,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 2016, at https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/rule-of-law/.

[5] Ibid., Section 5.

[6] See James Buchanan and Gordon Tullock, The Calculus of Consent: Logical Foundations of Constitutional Democracy. University of Michigan, 1962.

[7] I am assuming that the enumerated powers are properly interpreted, and that other clauses have not been unduly expanded, for example, the “Necessary and Proper” Clause or the Commerce Clause. Clearly, the Federal courts have expanded the scope of the meaning of enumerated powers and those clauses.

[8] Two Treatises of Government (1689), edited by Peter Laslett. Cambridge University, 1988, Chapter VII, section 94.

[9] See for example, Cato’s Letters, written by John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon in the 1720s and the works of Henry Bolingbroke during the same time period.

[10] It should also be noted that even where votes are by simple majority, the “winners” are still subject to laws, with some notable (and unfortunate) exceptions in practice.

Click Here to have the NEWEST essay in this study emailed to your inbox every day at 12:30 pm Eastern!

Click Here for the previous essay.

Click Here for the next essay.

Click Here to view the schedule of topics in our 90 Day Study on Congress.