Henry Cabot Lodge Senate Debate Of 1919 & The Treaty Of Versailles

LISTEN ON SOUNDCLOUD:

“Breaking the Heart of the World” – Henry Cabot Lodge and Constitutional Objections to the Treaty of Versailles

Background

World War I was fought from 1914-1918 and claimed the lives of nearly 9.5 million combatants. The United States entered the war in April, 1917, when Congress voted to declare war based upon President Woodrow Wilson’s war message arguing for American intervention with the expansive and idealistic foreign policy goal to “make the world safe for democracy.” The armistice was signed in November, 1918, and the war concluded on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of that month.

The Allies of Great Britain, France, and Italy sought a punitive peace against Germany and blamed that nation for starting the war. President Wilson, on the other hand, argued in his “Fourteen Points” for a lenient peace settlement that would prevent future wars by promoting international freedoms and self-determination. At the core of his proposal was destroying the old balance-of-power diplomacy by establishing a League of Nations that would help prevent war through deliberation as well as an Article X that would commit member nations to go to war to stop an “aggressor nation.”

On November 19, 1919, the Senate was abuzz with activity from an early hour since all observers expected a critical debate and vote to take place after a twelve-hour debate the previous day. Spectators flooded the gallery, jockeying for a good vantage point to view the historic event. Members of the press eagerly awaited news to report for their newspapers and spoke to their contacts about what to expect. The Senators gradually entered the chamber and exchanged pleasantries in a civil manner before the day’s vigorous debate ensued. Most eyes focused on sixty-eight-year-old Massachusetts Senator Henry Cabot Lodge.

The Senate was considering the Treaty of Versailles. The Senators did not disappoint the spectators and debated the treaty through lunch and dinner. After a ten-hour marathon debate in which they heard the arguments of their supporters and opponents, the Senators prepared to vote on the treaty. President Woodrow Wilson needed an affirmative two-thirds vote according to the Constitution to win ratification of the treaty he had personally negotiated for six months in France. On the first vote, the Senators rejected the treaty with reservations by a vote of 55-39. Another vote was taken on the treaty without reservations as the Wilson administration wanted and it was also defeated by a nearly identical vote of 53-38.

Lodge had reason to be satisfied with the defeat of the treaty. He was furious when President Wilson did not consult with him in his position as chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee before heading to Paris. Moreover, Wilson had made blatantly partisan appeals in the congressional elections of 1918 in which Republicans had won control of both houses and Lodge became the Senate Majority Leader. Wilson also did not include any Republicans on the peace delegation.

President Wilson had traveled to France to make peace in December, 1918, and Lodge questioned Wilson’s idealistic goals by asserting that the treaty should only focus on making it “impossible for Germany to break out again upon the world with a war of conquest.” The president briefly returned briefly in February, 1919, and on the evening of February 26, Senator Lodge and other members of the Foreign Relations Committee attended a dinner at the White House. Lodge sat impassively while the President spoke about a League of Nations to keep the peace. Lodge did not like what he heard. He peppered the president with a series of questions, and the answers confirmed many of Lodge’s fears that Article X of the League of Nations in the treaty would commit the United States to a war against any aggressor and bypass the constitutional requirement of a congressional declaration of war. After the dinner, Lodge told the media, “We learned nothing,” meaning that nothing new was presented. He was opposed to the United States being forced to “guarantee the territorial integrity and political independence of every nation on earth.”

Lodge believed in American constitutional principles and not committing U.S. troops to every conflict around the world. He was not opposed to a postwar treaty or even to a League of Nations, but he could not abide international commitments that violated the Constitution. He had the integrity to speak courageously and consistently to oppose the treaty with an international body that would compel America to go to war.

On the evening of Sunday, March 2, Lodge invited two other senators to his home to draft a resolution for their fellow senators to sign expressing their opposition to the League of Nations. Thirty-nine Republicans would sign the resolution and even some Democrats would express support.

On March 3, Lodge gave an important speech expressing his opposition to the League of Nations. Two weeks later, Lodge spoke in Boston and focused his attention on opposing Article X for violating American sovereignty, Congress’s prerogative to declare war, and the danger that Americans would be forced “to send the hope of their families, the hope of the nation, the best of our youth, forth into the world on that errand [to stop aggressor nations].” He continued, “I want to keep America as she has been – not isolated, not prevent her from joining other nations for these great purposes – but I wish her to be master of her fate.” In the Senate, Lodge made sure that any new members of the Foreign Relations Committee were opposed to the League of Nations.

When President Wilson returned to the United States with the signed Treaty of Versailles, he broke with precedent and presented the treaty to the Senate in person. As the president walked into the chamber with the bulky treaty under his arm, Lodge joked with Wilson and asked, “Mr. President, can I carry the treaty for you?” Wilson retorted, “Not on your life.” It was funny but revealed a truth that Lodge was the Senator who would determine the fate of the treaty and that Wilson would not entrust it to anyone and not accept any changes. During his address, President Wilson asked the Senate rhetorically, “Dare we reject it and break the heart of the world?”

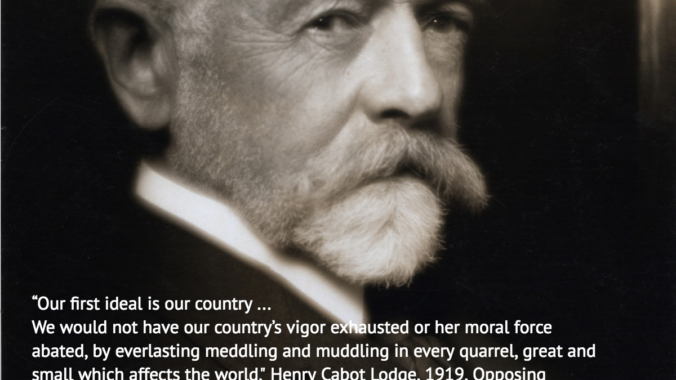

In August, Lodge reiterated to the Senate that Article X violated the principles of the Constitution. He stated that no American soldier or sailor could be sent overseas to fight a war “except by the constitutional authorities of the United States.” In addition, Lodge thought that the United States could not fight in every war around the globe and only needed to protect American interests. He said, “Our first ideal is our country . . . . We would not have our country’s vigor exhausted or her moral force abated, by everlasting meddling and muddling in every quarrel, great and small which affects the world.”

President Wilson had probably suffered a small stroke while in he was negotiating in Paris, and his health troubles caused him to be uncompromising. In September, Wilson further angered Lodge and the other opponents by taking the case for the League of Nations directly to the American people on a train-stop speaking tour. That tour was soon cut short when the president suffered a massive, debilitating stroke on October 2 back at the White House that incapacitated him for months. When the vote on his beloved League of Nations and Treaty of Versailles took place in the Senate, the president could not even get out of bed and walk.

Throughout the debate over the Treaty of Versailles and League of Nations, Senator Lodge stood firmly for the American Constitution and its principles. He did support world peace and hoped to avert another world war, but he would not sacrifice American principles in an attempt to achieve it. He sought to do what was right according to the Constitution.

Tony Williams is a Constituting America Fellow and a Senior Teaching Fellow at the Bill of Rights Institute. He is the author of six books including the newly-published Hamilton: An American Biography.

Click Here to have the NEWEST essay in this study emailed to your inbox every day at 12:30 pm Eastern!

Click Here for the previous essay.

Click Here for the next essay.

Click Here to view the schedule of topics in our 90 Day Study on Congress.

Thank you for your thoughts. Lodge is spot on with his assements.

I am studying the Second World War and post war military-industrial complex. It seems we have lost the understanding of foreign affairs. Perhaps, I need to go back further to connect the dots of our failures in government power and spending.