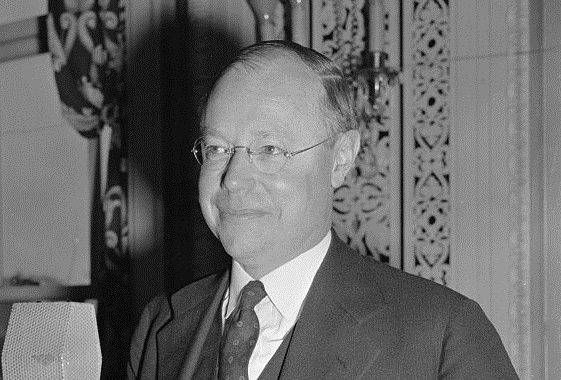

Robert Taft (1889-1953) – State Representative, U.S. Senator From Ohio; Son Of President William Howard Taft

LISTEN ON SOUNDCLOUD:

Leadership styles can often impact how political leaders and statesmen are remembered. FDR and Reagan were excellent communicators and exhibited great charm, Harry Truman was a man of the people and tough, JFK wrapped himself up in the myth of Camelot, Lyndon Johnson was a political operator and a master of the Senate.

Senator Robert A. Taft had none of these characteristics and is largely forgotten today. He seemed distant because he was often a master of facts and statistics rather than a masterful politician. As a result, he could seem cold and aloof. Yet, he was an important political figure of the mid-twentieth century whose career and political philosophy helped define the Republican Party of that era.

Taft was a scion of a leading Cincinnati family and the son of William Howard Taft who served as a Governor of the Philippines, Secretary of War, President, and later Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. They established a minor political dynasty, though not quite that of the Roosevelts, Kennedys, or Bushes.

Taft was raised in a life of affluence in Cincinnati and around the country and world. He may have inherited many opportunities but worked hard to succeed in becoming the valedictorian at Yale University and Harvard Law School. He became a corporate lawyer, married, and engaged in local philanthropic activities. He never tried to win over friends and political allies with a congenial personality but was more interested in a good character and strong work ethic.

World War I was a defining event in Taft’s life and his political philosophy. He opposed American intervention but wanted to defend American neutral rights and national security. He served with Republican Herbert Hoover in the Food Administration during the war and the American Relief Administration in Europe helping to feed the shattered and starving populations there after the war. During his time in Europe, he developed an antipathy to becoming involved in European affairs and hated both the collective ideologies of bolshevism and fascism that took hold in Europe. Above all, he opposed the unlimited global commitment that seemed to come with the Treaty of Versailles and League of Nations. He developed a lifelong aversion to the crusading foreign policy spirit of Wilsonianism to “make the world safe for democracy.”

Despite being a relative introvert, Taft ran for public office out of a sense of family and personal duty to serve the public. He served in the Ohio state legislature from 1920 to 1926, where he was interested in tax reform and resisted the influence of the Ku Klux Klan.

The Great Depression that gripped the nation and the New Deal that FDR conceived to battle the economic crisis continued to shape Taft’s thinking and serving in public office. He opposed the New Deal political philosophy that expanded the federal welfare state and powers of executive agencies. He thought that the New Deal was substituting “an autocracy of government for a government of law.” He feared that the growth of government would negatively impinge upon personal liberty, upset the balance of federalism, and create a massive state with huge budget deficits.

Nevertheless, Taft was a midwestern conservative Republican who was often equally suspicious of Wall Street as he was of Washington, D.C. While he opposed massive regulatory intrusion in the private market and confiscatory taxes, he fought against monopoly and was not a believer in laissez-faire. He supported reasonable regulation, higher taxes (and lower spending) to balance budgets, and a basic social safety net.

Taft was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1938, and quickly established himself as a hardworking, if somewhat dull and lackluster, member. Characteristically, he studied hard to become an expert on the issues rather than spending time making backroom deals and pressing the flesh. He served on several committees including the Education and Labor Committee.

As tyrannies marched their war machines across Asia, Africa, and Europe during the 1930s, the New Deal gave way to foreign policy issues. Unsurprisingly, Taft adopted a thoughtful and relatively flexible isolationist stance. He did not want to get involved in the coming war, but supported preparedness to defend American shores. He supported selling other countries arms so that they could defend themselves without American intervention. He feared that the wily FDR was leading the country into war and opposed the peacetime draft because of its impact on individual liberty.

Taft supported American entry into World War II after Pearl Harbor and the German declaration of war. During the war, he was just as concerned about the rise of the warfare state with its budget deficits, wage and price controls, huge government spending, and threats to civil liberties as he was in peacetime with the New Deal welfare state. Taft consistently defended the principles of limited government to protect individual liberty in a democracy.

During the war, Senator Taft had presidential aspirations but always seemed to lack the political skills necessary to win the Republican nomination or attain the highest office. Moreover, FDR was simply too popular as commander-in-chief even if Republicans and conservative Southern Democrats began chipping away at the New Deal electoral coalition.

Taft entered the postwar world with his persistent doubts about liberal internationalism and government programs at home. Taft opposed the United Nations much as he had the League of Nations and was a voice against American commitments abroad during the early Cold War. He did not want to impose democracy on any nation or tell them how to govern their foreign policy decisions. Indeed, he was a strong anti-imperialist who warned against America putting “Our fingers…in every pie” with unlimited global interventions.

In 1947, Taft was the co-sponsor of the Taft-Hartley Act that is synonymous with his historical reputation. Contrary to historical opinion, he was not antilabor and even supported the right to strike. Even President Truman called for controls on strikes and federal power to intervene during a wave of postwar strikes across the nation. Taft’s expertly guided his bill through Congress. It banned the closed shop in which workers were forced to join the union as a condition of employment, banned secondary boycotts, and allowed both employers and unions to seek federal injunctions. Truman vetoed the bill, but the Republicans controlled both houses of Congress after the 1946 elections, and overrode the veto.

After his reelection for a third term in the Senate, Taft reached the height of his power as he nearly won the Republican presidential nomination in 1952 and was elected Senate majority leader. True to his principles, he denounced Joseph McCarthy’s anti-Communist smear tactics and American intervention to save the French war effort in Vietnam. However, in 1953, he discovered he had cancer and was dead within the year.

Taft was known as “Mr. Republican” because of his allegiance to limited government at home and a non-interventionist foreign policy that represented mainstream Republican thinking during the mid-twentieth century. While not the most gregarious politician, he was a well-respected, diligent statesman who dedicated his life to an ideal of public service.

Tony Williams is a Constituting America Fellow and a Senior Teaching Fellow at the Bill of Rights Institute. He is the author of six books including the newly-published Hamilton: An American Biography.

Click Here to have the NEWEST essay in this study emailed to your inbox every day at 12:30 pm Eastern!

Click Here for the previous essay.

Click Here for the next essay.

Click Here to view the schedule of topics in our 90 Day Study on Congress.

Thank for the essay. I knew virtually nothing about Taft. Now that I do know more I like his positions on many issues.

PSD