LISTEN ON SOUNDCLOUD:

Intergovernmental Competition: Are we in a “Race to the Bottom”?

Grants are just one way of transferring money and there are alternative financial arrangements that better meet the standards of joint-influence and joint-benefit, such as GRS. Rarely is it the case that the specific goals outlined by narrow grant programs perfectly meet the needs or desires of a state community. And, the costs of administering a grant seldom justify the federal government’s insistence that states participate. It is often overlooked that states could simply fund the government program themselves, without federal oversight or administrative duplication, if enough political will existed within the state community for that service.

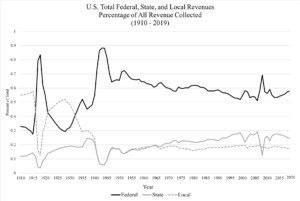

Nevertheless, we should first recognize that the federal government might have certain advantages when it comes to taxing and spending, which helps to justify the need for any intergovernmental cooperation at all. The states do not exist independent of one another, and an important principle outlined in the last essay was that the taxing and spending decisions reached by one state government necessarily affect the fiscal capabilities of all the other states.

In the best case scenario, this has huge advantages for a diverse national community. People get to choose what their states look like, and they can exercise an important check on state governments that tax and spend the peoples’ money unjustly: they can leave!

States, therefore, compete with one another for residents, for business, and ultimately, for tax dollars. And those competitive pressures incentivize state and local governing officials to provide the best government for the lowest cost.

Yet, sometimes that competition has negative effects — what political economists might label a “negative externality.” When the savings created by one state’s actions impose costs on other political communities, competition produces inefficiencies. This is best illustrated by state variation in how much is spent on environmental regulation and clean-up. States that are literally “up-river” can exact exorbitant costs on other states through their inaction. Likewise, in trying to attract business to their state, one state might dismantle regulations placed on corporations; neighboring states might follow suit in order to keep business from leaving. State-level variation and competition might, in other words, work against certain national goals, creating a “race to the bottom” where states undercut one another to create advantages in the short-term, but impose long-term costs on the national political community.

Such is the rationale for the single largest intergovernmental program in the United States: Medicaid. The provisioning of Medicaid reflects a national goal (healthcare for the poor) and is structured so as to reduce the degree of competition between states in administering benefits. Almost a third of all state spending goes towards Medicaid payments, and that number is increasing; 20 percent of funding is raised solely by the states, up from just 9-percent in 1990. The federal government dictates minimum eligibility requirements, but each state is left free to fund the program to desired levels and set additional requirements on recipients and providers of Medicaid services. The 2010 Affordable Care Act — “Obamacare” — would have required states to enroll citizens who made up to 133% of the federal poverty line, but the Supreme Court struck down mandatory expansion, which reinforced the joint-nature of the program.[1] As of early 2019, only 36 states have expanded Medicaid as a result. Moreover, under the Trump administration, a number of states have experimented with requiring work requirements for eligible participants. The federal courts have struck down three states’ efforts, but it is an open legal battle over just how flexible Medicaid will remain, as it consumes a larger portion of state budgets.[2]

Fiscal Independence: Should we Blame the States?

No doubt some readers, in thinking through the examples about the “race to the bottom” might view such competition as a healthy impulse: it has the high potential to limit environmental regulation and corporate taxation, for instance. One man’s race to the bottom is another man’s dream of limited government.

However, American political history suggests that, in the long run, rather than maintaining a de-regulated system of limited government, excessive competition between the states has provided the federal government an enduring rationale to step in and impose requirements on a national level, with little involvement from the states or cities. Hamilton warned of this possibility in 1789, writing that while “the people of each State would be apt to feel a stronger bias towards their local governments than towards the government of the Union,” this would only be the case “unless the force of that principle should be destroyed by a much better administration of the latter [federal government].”[3]

The logic of concurrent taxation and the promise of intergovernmental competition should make us reconsider one of the dominant strategies promoted by proponents of limited government in the 20th century: tax restrictions within state constitutions.

As discussed in the previous essay, citizens of the various states have long turned to their own state constitutions to regulate the public coffers, often saving future generations from unmanageable levels of government debt. In 1978, voters in California continued this tradition and passed Proposition 13 — a citizen-led ballot initiative that placed hard restrictions on the ability to increase property tax rates and reassess the value of commercial and residential real estate.

On the one hand, such restrictions have forced government officials to scrimp, save, and justify every expense, particularly at the local level, and often to the benefit of the taxpayer. In this regard, the “tax revolt” unearthed by Proposition 13 worked. In 1976, Californians had the sixth-highest “tax burden” in the country, at 12.2-percent — a measure of how much annual income each resident pays in state and local tax. In 2019, they rank 11th, with an individual’s burden down to 9.47-percent of annual income.[4]

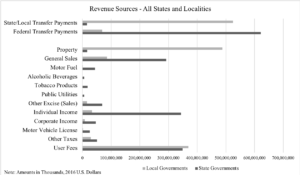

On the other hand, it is not so clear that constitutional prohibitions — in California or in other states — always produce a system of public finance that allows Hamilton’s paradoxical logic to function properly. In restricting a state government’s taxing powers, it loses the ability to check the federal government, thereby reducing the amount of fiscal competition (and cooperation), the framers of the Constitution favored. Competition among the states, in other words, must be balanced out by competition between the states and the federal government. While it is also fair to critique the redistributive effects of the constitutional prohibitions — Proposition 13 overwhelmingly favors long-term residents over new arrivals, decreases the financial incentive for selling a home, and inflates property values — it is this intergovernmental consequence that is most problematic. Local governments, dependent on property tax, responded not by curtailing services that citizens still desired, but by requesting assistance from the state. State governments grew in power, but then faced financial hardship of their own as they competed with localities over a diminished tax base. The state government then turned to the federal government. Overall spending, when considering intergovernmental transfers, has climbed, as have debt levels. And, since those restrictions are protected by high constitutional thresholds, they limit the ability of residents to take back authority from the general government.

In closing, I emphasize that if we are to understand what state and local governments do– and what they are capable of doing — we need to follow their money. Budgeters and politicians can devise any number of complicated schemes for regulating the public purse, but, as Hamilton, again, forewarns, the entire constitutional system is “left to the prudence and firmness of the people; who, as they will hold the scales in their own hands, it is to be hoped will always take care to preserve the constitutional equilibrium between the general and the State governments.”[5]

Public finance is ultimately a decision about what type of government people want. And such confusion and discord in state and local finances is the clearest indication that few Americans actually know what type of government they want. They want low taxes and lots of services. The types of trade-offs — between revenues that can go to the public purse, and services provided by multiple governments — are seldom discussed, and increasingly, fail to meet the standards of constitutional federalism as a result.

Nicholas Jacobs is a Faculty Research Associate in the School of Civic and Economic Thought and Leadership at Arizona State University, where he also serves as the assistant project director of the Living Repository of the Arizona Constitution. He has published numerous scholarly articles on intergovernmental politics, American political history, and the American presidency.

Click Here to have the NEWEST essay in this study emailed to your inbox every day!

Click Here to view the schedule of topics in our 90 Day Study on Congress.

[1] National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius, 567 U.S. 519 (2012)

[2] Nicholas F. Jacobs and Connor M. Ewing. 2018. “The Promises and Pathologies of Presidential Federalism.” Presidential Studies Quarterly 48 (3): 552-569.

[3] Federalist 17

[4] Tax Foundation. State and Local Tax Burdens. URL: https://taxfoundation.org/state-and-local-tax-burdens-historic-data/

[5] Federalist 31