Guest Essayist: Horace Cooper, Constituting America Fellow

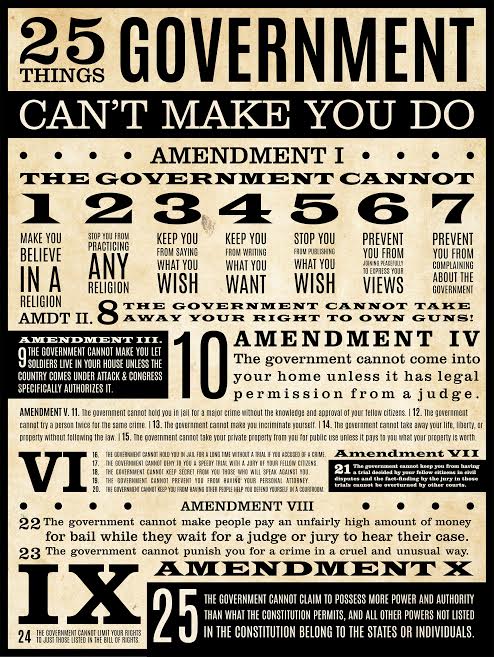

Click here to buy the poster below!

The First Ten Amendments to the United States Constitution make up what is called “The Bill of Rights.” This remarkable collection of limitations on the power of the national government was written by James Madison and heavily influenced by George Mason. Today it operates as a barrier to oppressive government at all levels and protects citizen liberty.

The First Ten Amendments to the United States Constitution make up what is called “The Bill of Rights.” This remarkable collection of limitations on the power of the national government was written by James Madison and heavily influenced by George Mason. Today it operates as a barrier to oppressive government at all levels and protects citizen liberty.

While most Americans at the time of the writing of the US Constitution agreed that the Articles of Confederation had failed to provide the former colonies with the powers needed to insure the experiment in self-government would succeed, there was another contingent who argued that any new and expanded powers given to the central government must be overlaid with specific limits in order to ensure that the citizens rights wouldn’t be trampled. They argued that rather than limiting principles, there should be specific prohibitions on what government is allowed to do, especially in the context of its treatment of its citizens.

The two camps generally called themselves Federalists and Anti-Federalists. While the design and makeup of the original Constitution is a triumph of the Federalists, the Bill of Rights represents the success of the Anti-Federalists.

Timeless in their rigor and value, the Bill of Rights has proven to be a brilliant tool to limit government excesses and insure that the individual has the kinds of freedoms that many of us take for granted. While the writers of the Constitution created a system of checks and balances that cause the three branches of government to be limited in their ability to achieve hegemony vis-à-vis the other, it is the Bill of Rights that has done more to protect individual liberty — doing so by specifically placing limits on government power.

While the Federalists won the day with the original draft of the Constitution, it soon became clear that the American people wouldn’t accept the Constitution unless a Bill or Rights was agreed to. Shortly after meeting, the first Congress began that process. Originally 17 Amendments or changes to the Constitution were presented and passed by the House of Representatives. Of those 12 were passed by the United States Senate and sent to the states for approval in August of 1789. 10 of these were approved (or, ratified) with George Mason’s state of Virginia becoming the last to ratify the amendments on December 15, 1791.

Indubitably, liberties that we take for granted as Americans find their origin in the Bill of Rights. One key aspect of the Bill of Rights is that instead of expanding or authorizing the powers of the central government, the Bill of Rights squarely and directly treats government power as a potential threat to citizen liberty and places clear and unequivocal barriers to government action. More a list of what government cannot do, the Bill of Rights provides a zone of liberty that makes our American system of citizenship the envy of the world.

The supporters of the concept of the Bill of Rights understood that government’s tendency was to expand and over-run the individual. And the beauty of the Bill of Rights, its simplicity is, it limits government power and by doing keeps Americans free.

Amendment I

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.

The government cannot make you believe in a religion.

The government cannot keep you from practicing any religion you choose.

The government cannot keep you from saying what you wish.

The government cannot keep you from writing what you want.

The government cannot stop you from publishing what you wish.

The government cannot keep you from joining together peacefully with others to express your views.

The government cannot prevent you from complaining about what the government or others are doing to you.

The framers understood that freedom of faith, thought, political belief and other forms of expression were central to citizen liberty and they specifically barred government action in this arena. Rather than leave to the majority whether Catholics, Protestants, Jews or even people of no faith would receive preference by the national government, the First Amendment insures that no religious group would be preferred nor would any be penalized. It also prevents the government from using coercive powers to reward certain political thoughts or writings as well as punishing the same. Finally it further insures that citizens have the right to complain specifically about the activities of the government and to engage in demonstrations as well as formally taking measures to get the government itself to change policies.

Amendment II

A well regulated militia, being necessary to the security of a free state, the right of the people to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed.

The government cannot take away your right to own and keep guns.

Rather than leave firearm access to the government, our Bill of Rights explicitly insures that the right to bear and own firearms is a fundamental right – not a privilege – that resides with every citizen.

Amendment III

No soldier shall, in time of peace be quartered in any house, without the consent of the owner, nor in time of war, but in a manner to be prescribed by law.

The government cannot make you let soldiers to live in your house unless the country comes under attack and Congress specifically authorizes it.

Even though war-making activity is the quintessential government duty and activity, this power is not unlimited. While it might be cost-effective or even efficient, government has to respect that our homes are our property and may not be overtaken by the military during peace-time and during war only in a legal manner determined by Congress.

Amendment IV

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

The government cannot come into your home unless it has legal permission from a judge.

Perhaps one of the greatest threats that the citizen faces is the potential that the central government will use force to enter our property whether under pretext of solving crimes or ferreting out critics of the government residing therein. The founders recognized that the principle that the individual citizen was the “king” of his own “castle” especially when the government sought unlawful entry was a powerful limit on government excesses. Juxtaposing judges and other magistrates before the government can take, enter or search property protected liberty in the 18th century and the 21st as well.

Amendment V

No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a grand jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the militia, when in actual service in time of war or public danger; nor shall any person be subject for the same offense to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.

The government cannot hold you in jail for a major crime without the knowledge and approval of your fellow citizens.

The government cannot try a person twice for the same crime.

The government cannot make incriminate yourself.

The government cannot take away your life, liberty, or property without following the law.

The government cannot take your private property from you for public use unless it pays to you what your property is worth.

King George and his predecessors in England had the ability to falsely accuse and even imprison or execute his opponents without even a pretext of any real violation of the law. Our system rejects this idea. The Bill of Rights requires that your fellow citizens be presented with the charges against you and that those charges not be presented to you more than once or that you or your property be taken from you without having legal recourse to challenge it. Americans can’t be forced to give incriminating testimony against themselves and their assets can’t be confiscated by the government without being justly compensated.

Amendment VI

In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the state and district wherein the crime shall have been committed, which district shall have been previously ascertained by law, and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the assistance of counsel for his defense.

The government cannot hold you in jail for a long time without a trial if you are accused of having broken the law.

The government cannot deny to you a speedy trial with a jury of your fellow citizens.

The government cannot keep secret from you those who will speak against you.

The government cannot prevent you from having your personal attorney.

The government cannot keep you from having other people help you defend yourself in a courtroom.

Instead of the use of secret trials and star chambers, our system specifically requires that when people are accused the trials must not be unnecessarily lengthened and must be held in public. The individuals who decide guilt or innocent – jurors – must be impartial and residents of the area where the accused crime was to have occurred. Instead of announcing new charges mid-trial, the government must announce the charges with specificity and must present witnesses against him and must allow him to bring in his own witnesses to testify on his behalf and may not prevent him from having legal assistance if he chooses.

Amendment VII

In suits at common law, where the value in controversy shall exceed twenty dollars, the right of trial by jury shall be preserved, and no fact tried by a jury, shall be otherwise reexamined in any court of the United States, than according to the rules of the common law.

The government cannot keep you from having a trial decided by your fellow citizens in civil disputes and the fact-finding by the jury in those trials cannot be overturned by other courts.

Civil cases, like criminal cases provide potential opportunity for liberties to be risked. Our founders guaranteed that civil disputes will be subject to jury trials instead of the whims of government magistrates and also that the findings of jurors can’t be second guessed by judges. The government can’t pick sides or use its judicial appointees to try to influence the outcomes of civil disputes.

Amendment VIII

Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.

The government cannot make people pay an unfairly high amount of money for bail while they wait for a judge or jury to hear their case.

The government cannot punish you for a crime in a cruel and unusual way.

The government is not allowed to skip the trial phase by holding citizens in jail with high bails having nothing to do with the severity of their crime or any flight risks they pose. Even when citizens are found guilty, the federal government may not assess fines that aren’t connected with the severity of their crime nor may they issue punishments that are depraved and unduly harsh.

Amendment IX

The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.

The government cannot limit your rights to just those listed in the Bill of Rights.

Reaffirming the anti-federalists view that government tends to expand whenever and however it can and ultimately crowding out the rights and privileges of its citizens, our founders have made it clear that the Constitution and even the Bill of Rights do not attempt to outline every existing natural or inalienable right of citizens.

Amendment X

The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the states, are reserved to the states respectively, or to the people.

The government cannot claim to possess more power and authority than what the Constitution permits, and all other powers not listed in the Constitution belong to the states or individuals.

Since the Constitution is a charter of specific and enumerated powers, there are rights that exist above and beyond those addressed in it. Those powers and rights that are not specifically addressed in the Constitution and those powers that are not banned by states through the Constitution are real and duly allowed to be exercised by the states and the people.

Horace Cooper, a Constituting America Fellow, is co-chairman for Project 21’s National Advisory Board and adjunct fellow with the National Center for Public Policy Research. In addition to having taught constitutional law at George Mason University, Mr. Cooper was general counsel to U.S. House Majority Leader Dick Armey.