LISTEN ON SOUNDCLOUD:

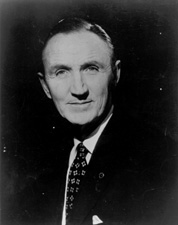

Michael Joseph Mansfield served as both representative and senator from the state of Montana, and would go on to serve as United States Ambassador to Japan. Mansfield was born March 16, 1903 in New York though his life soon took a turn for the difficult. By the age of seven, Mike Mansfield’s mother had passed away and he was sent to live with an aunt and uncle in Great Falls Montana. At fourteen he dropped out of school and joined the Navy during WWI. Mansfield would serve on Naval convoys until his real age was discovered and he was discharged. Mansfield would rejoin the military and serve with the Army and Marine Corps until 1922; while a Marine, Mansfield would serve in China and the Philippines which fostered a lifelong interest in the East.

After his military service, the would-be Senator Mansfield returned to Butte, Montana and found a job in a mine. Mansfield’s wife Maureen Hayes encouraged him to pursue his education and by 1934 he had completed his high school, bachelor’s and master of arts. Passionate about politics and history, he taught courses on Latin America and East Asia until 1942 when he won the house seat for MT-1 as a Democrat, formerly held by Jeanette Rankin (a committed pacifist and the sole vote against entry into World War Two).

As a member of the House, Mansfield sat on the Foreign Affairs Committee and quickly garnered a reputation as an expert on Asia. In 1944 he served on several congressional trips to China. His report to the House criticized Chang Kai Shek’s nationalist movement as only tacitly democratic and in practice oppressive, while Mao’s communist forces retained broader popular support. Despite what in hindsight seem to be accurate statements, they were magnified in the partisan politics of the 1950 Senate campaign, as well as in the context of the “loss” of China in May of that year to Mao’s forces. He ran again in 1952 for Senate and was successful, despite the opposition of incumbent Republican Zales Ecton and the campaigning of the infamous Senator Joseph McCarthy.

Remembered today for his staunch opposition to the Vietnam war, Mansfield, alongside fellow Catholic, and fellow junior Senator John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts, aided in the ascension of Ngo Dinh Diem. A devout Catholic, Diem resided at a seminary in New Jersey as a guest of Cardinal Spellman; while he was an efficient bureaucrat in Vietnam, he had a deep hatred for communism and resentment of French colonial rule which led to exile in America. Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas organized the 1953 meeting between Kennedy, Mansfield and Diem which was deeply influential for the two Senators. Douglas assured Kennedy and Mansfield that Diem was wildly popular in Vietnam, while Diem convinced them that the French would falter in their struggle against Ho Chi Minh’s guerillas.

The next year brought Diem’s predictions to life when the French garrison at Dien Bien Phu was besieged and destroyed by General Vo Nguyen Giap. Mansfield, among a handful of other senators, recommended Diem to Eisenhower’s Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, as the solution to the impending power vacuum in South Vietnam, as France worked to negotiate with Minh and the communists.

Diem’s tenure as Prime Minister was quickly challenged in 1956, when a conflict between his government and several sects (some criminal, some backed by the French) broke out. A memo from Kenneth T. Young a state department advisor on Vietnam to Walter S. Robertson Undersecretary of State (included in the Pentagon Papers Pentagon Papers V B 3c, 946 ) notes Mansfield “would have us stop all aid to Viet-Nam except of a humanitarian nature…” should State withdraw its support of Diem.

Outside of Asia, Mansfield was a strident critic of abuses and failures by the intelligence community. He grilled CIA director Allen Dulles after their failure to anticipate the Hungarian uprising, as well as British and French involvement in the Suez Canal crisis in 1956. Mansfield went so far as to call for a joint congressional committee to investigate and oversee the CIA. Senate Majority Leader Lyndon B. Johnson put this plan on ice when he appointed Mansfield Assistant Majority Leader.

In 1961, with Johnson as Vice President, Mansfield became Senate Majority Leader. To this day, Mansfield is the longest serving majority leader. A far different man from the browbeating Johnson, Mansfield brought the demeanor of a scholar to the Senate, where despite strong ideological convictions, sought a collegial and professional environment. Mansfield sought a sharp break from the way business had been done under Johnson, though he’d go on to shepherd and support President Johnson’s great society initiatives.

Conditions under Diem’s leadership in Vietnam deteriorated. In 1962 President Kennedy sent Mansfield (as well as a morose Vice President Johnson) to Vietnam in an attempt to understand conditions on the ground. Mansfield returned with a damning report on the progress of the South Vietnamese government and efficacy of American foreign policy there. While he praised his old friend Ngo Dinh Diem as “a dedicated, sincere, hardworking, incorruptible and patriotic leader” he noted that “Viet Nam, outside the cities, is still an insecure place which is run at least at night largely by the Vietcong. The government in Saigon is still seeking acceptance by the ordinary people in large areas of the countryside. Out of fear or indifference or hostility the peasants still withhold acquiescence, let alone approval of that government. In short, it would be well to face the fact that we are once again at the beginning of the beginning.” Mansfield concluded his 1962 report with this sobering question: “…how much are we ourselves prepared to put into Southeast Asia and for how long in order to serve such interests as we may have in that region? Before we can answer this question, we must reassess our interests, using the words ‘vital’ or ‘essential’ with the greatest realism and restraint in the reassessment.”

Kennedy continued to expand America’s role in South Vietnam, despite little to show for the billions already spent. Mansfield’s friend, President Diem was assassinated in a military coup on November 2, 1963. His friend, President John F. Kennedy would fall to an assassin’s bullet a mere 20 days later.

Mansfield increased in his skepticism of American intervention in Vietnam to outright opposition. He offered controversial Amendments to Military Authorization act in the 1970s which limited how research funds were spent. In 1976 he retired and in 1977 was appointed by President Carter to serve as Ambassador to Japan. He would remain in the role until 1988, and in 1989 was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by Ronald Reagan. The Senator passed away on October 5, 2001 and is interred with his wife at Arlington National Cemetery.

James Legee, Visiting Lecturer, Framingham State University Department of Political Science

Click Here to have the NEWEST essay in this study emailed to your inbox every day at 12:30 pm Eastern!

Click Here for the previous essay.

Click Here for the next essay.

Click Here to view the schedule of topics in our 90 Day Study on Congress.