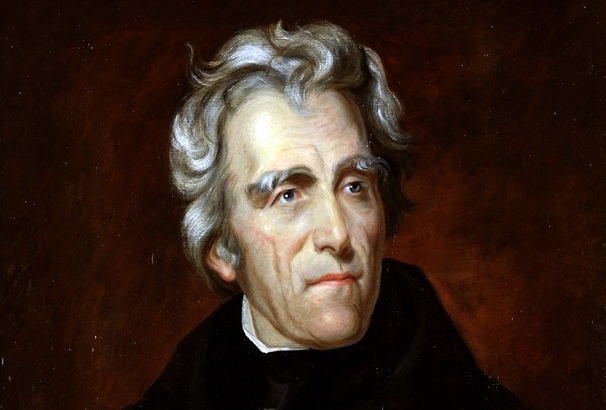

March 4, 1829: Andrew Jackson is Inaugurated U.S. President and the Democratic Party is Formalized

Andrew Jackson started out as a lawyer and grew in politics. By the end of the War of 1812 between the United States and Britain, Jackson was a military hero of great influence. Former governor of Tennessee, he defeated John Quincy Adams in 1828, became the seventh president and first Democratic Party president, and helped found the Democratic Party.

Jackson’s biography reads larger than life. He was born in 1767 in a backwoods cabin, its precise location unknown. He was scarred by a British officer’s sword, orphaned at fourteen and raised by uncles. He was admitted to the bar after reading law on his own, one year a Congressman before being elected to the U.S. Senate, a position he then resigned after only eight months. He was appointed as a circuit judge on the Tennessee superior court. He became a wealthy Tennessee landowner, and received a direct appointment as a major general in the Tennessee militia which led, after military success, to direct appointment to the same rank in the U.S. Army. He was an underdog victor and national hero at the Battle of New Orleans, and conducted controversial military actions in the 1817 Seminole War. He experienced disappointment in the 1824 presidential election, but success four years later. He survived the first assassination attempt of a United States President and was the first President to have his Vice-President resign. He appointed Roger Taney (Dred Scott v. Sanford) to the U.S. Supreme Court. President Jackson died in 1845 of lead poisoning from the two duelist bullets he carried for years in his chest, one for forty years. You couldn’t make this biography up if you tried.

President Andrew Jackson is a constitutionalist’s dream. Few U.S. Presidents intersected the document of the U.S. Constitution as often or as forcefully during their terms as did “Old Hickory.” From the Nullification Crisis of 1832, to “killing” the Second National Bank, to his controversial “Trail of Tears” decision, Jackson seemed to attract constitutional crises like a magnet. When the Supreme Court handed down its opinion in Worcester v. George, Jackson is purported to have said “Well, John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it.” It has not been reported whether Thomas Jefferson’s moldering corpse sat up at hearing those words, but I think it likely.

Jackson’s multiple rubs with the Constitution preceded his presidency. As the General in charge of defending New Orleans in late 1814, he suspended the writ of habeas corpus, which the Constitution gives only Congress the power to suspend,[1] unilaterally declaring martial law over the town and surrounding area. Habeas corpus, the “great and efficacious writ,”[2] enjoyed a heritage going back at least to Magna Carta in 1215, a fact Jackson found not compelling enough in the light of the civilian unrest he faced. As Matthew Warshauer has noted: “The rub was that martial law saved New Orleans and the victory itself saved the nation’s pride… Jackson walked away from the event with two abiding convictions: one, that victory and the nationalism generated by it protected his actions, even if illegal; and two, that he could do what he wanted if he deemed it in the nation’s best interest.”[3]

It would not be Jackson’s last brush as a military officer with arguably illegal actions. Three years later, during the First Seminole War, he found his incursion into Spanish Florida, conducted without military orders, under review by Congress. Later, when running for President, Jackson had to defend his actions: “it has been my lot often to be placed in situations of a critical kind” that “imposed on me the necessity of [v]iolating, or rather departing from, the constitution of the country; yet at no subsequent period has it produced to me a single pang, believing as I do now, & then did, that without it, security neither to myself or the great cause confided to me, could have been obtained.” (Abraham Lincoln would later offer a not dissimilar defense of his own unconstitutional suspension of Habeas Corpus in 1861).

After the ratification of the Adams–Onís Treaty in 1821, settling affairs with Spain, Jackson resigned from the army and, after a brief stint as the Governor of the Territory of Florida, returned to Tennessee. The next year he reluctantly allowed himself to be elected Senator from Tennessee in a bid (by others) to position him for the Presidency.

In the 1824 election against John Quincy Adams, Senator Jackson won a plurality of the electoral vote but, thanks to the Twelfth Amendment and the political maneuvering of Henry Clay, he was defeated in the subsequent contingent election in favor of “JQA.” Four year later, while weathering Federalist newspapers’ charges that Adams was a “murderer, drunk, cockfighting, slave-trading cannibal” the tide finally turned in Jackson’s favor and he won an Electoral College landslide.

As his inauguration day approached, I wonder how many Americans knew just how exciting would be the next eight years? On March 4, 1829, Jackson took the oath as the seventh President of the United States.

In an attempt to “drain the swamp,” he immediately began investigations into all executive Cabinet offices and departments, an effort that uncovered enormous fraud. Numerous officials were removed from office and indicted on charges of corruption.

Reflecting on the 1824 election, in his first State of the Union Address, Jackson called for abolition of the Electoral College, by constitutional amendment, in favor of a direct election by the people.

In 1831, he fired his entire cabinet.[4]

In July 1832, the issue became the Second National Bank of the United States, up for re-chartering. Jackson believed the bank to be unconstitutional as well as patently unfair in the terms of its charter. He accepted that there was precedent, both for the chartering (McCulloch v. Maryland (1819) as well as rejecting a new charter (Madison, 1815), but, perhaps reflecting his reaction to Worcester v. Georgia earlier that year, he threw down the gauntlet in his veto message:

“The Congress, the Executive, and the Court must each for itself be guided by its own opinion of the Constitution. Each public officer who takes an oath to support the Constitution swears that he will support it as he understands it, and not as it is understood by others. It is as much the duty of the House of Representatives, of the Senate, and of the President to decide upon the constitutionality of any bill or resolution which may be presented to them for passage or approval as it is of the supreme judges when it may be brought before them for judicial decision. The opinion of the judges has no more authority over Congress than the opinion of Congress has over the judges, and on that point the President is independent of both. . .”[5] . (emphasis added)

Later that same year came Jackson’s most famous constitutional crisis: the Nullification Crisis. Vice President John C. Calhoun’s home state of South Carolina declared that the federal Tariffs of 1828 and 1832 were unconstitutional and therefore null and void within the sovereign boundaries of the state, thus “firing a shot across the bow” of Jackson’s view of federalism. The doctrine of nullification had been first proposed by none other than James Madison and Thomas Jefferson thirty-four years earlier and it retains fans today. South Carolina eventually backed down but not before Jackson’s Vice President, J.C. Calhoun resigned to accept appointment to the Senate and fight for his state in that venue, and not before Congress passed the Force Bill which authorized the President to use military force against South Carolina.

In 1834, the House declined to impeach Jackson, knowing the votes were not there in the Senate for removal and settled on censure instead, which Jackson shrugged off.

Yet in 1835, Jackson sided with the Constitution and its First Amendment by refusing to block the mailing of inflammatory abolitionist mailings to the South even while denouncing the abolitionists as “monsters.”

Today, some people compare our current President to Jackson, including President Donald Trump himself. Others disagree. There are indeed striking similarities, as well as great differences. Although coming from polar opposite backgrounds, both are populists who often make pronouncements upon the world of politics without the filter of “political correctness.” Further comparisons are found in the linked articles.

Thanks to the great care taken by the men of 1787, the “American Experiment” has weathered many a controversial president, such as Andrew Jackson – and we will doubtlessly encounter, and hopefully weather many more.

Gary Porter is Executive Director of the Constitution Leadership Initiative (CLI), a project to promote a better understanding of the U.S. Constitution by the American people. CLI provides seminars on the Constitution, including one for young people utilizing “Our Constitution Rocks” as the text. Gary presents talks on various Constitutional topics, writes periodic essays published on several different websites, and appears in period costume as James Madison, explaining to public and private school students “his” (i.e., Madison’s) role in the creation of the Bill of Rights and the Constitution. Gary can be reached at gary@constitutionleadership.org, on Facebook or Twitter (@constitutionled).

Click Here to have the NEWEST essay in this study emailed to your inbox every day!

Click Here to view the schedule of topics in our 90-Day Study on American History.

[1] U.S. Constitution; Article One, Section 9, Clause 2

[2] Sir William Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England.

[3] https://ap.gilderlehrman.org/essay/andrew-jackson-and-constitution

[4] Secretary of State Martin Van Buren, who had suggested the firing, resigned as well to avoid the appearance of favoritism.

[5] http://www.americanyawp.com/reader/democracy-in-america/andrew-jacksons-veto-message-against-re-chartering-the-bank-of-the-united-states-1832/

Join the discussion! Post your comments below.

Your feedback and insights are welcome.Feel free to contribute!