March 14, 1794: Eli Whitney Receives a Patent for His Invention of the Cotton Gin

The Making of King Cotton: Eli Whitney’s Dogged Inventiveness

When one considers the great inventors of nineteenth-century America, few surpass Eli Whitney in both personal tenacity and the broader impact their works had on industrialization. Born on December 8, 1765 in Massachusetts, Whitney came of age during the American Revolution. As a boy, he enjoyed tinkering in his family’s workshop. One story tells that he stayed home on a Sunday to take apart his father’s watch while the rest of his family went to church. At the age of 12, Whitney created a violin—an incredible feat at such a young age. However, his tinkering was no mere hobby. The American Revolution was taking a toll on the colonial economy as men left their jobs to fight in the war or dedicated their trades to creating military equipment. Whitney heard that farmers around his home needed nails, and he soon created a forge to meet the demand.

After the American Revolution, Whitney studied and worked hard to pass entrance exams and pay to attend Yale. His intelligence and skills caught the eye of officials at the college, one of whom helped Whitney secure a job as a tutor in the South. The young man left his home area for South Carolina after graduation, but the job ended up falling through. Fortunately, Whitney had met Catherine Greene, the widow of Revolutionary War General Nathanael Greene, on his way south and accepted a position on her plantation in Savannah, Georgia.

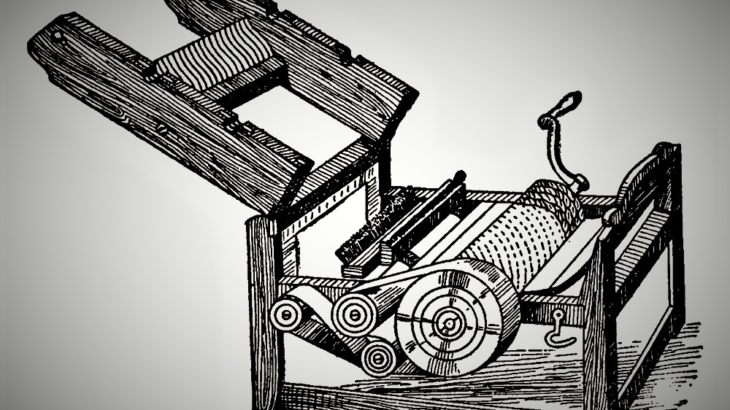

On the Greene plantation, the New Englander witnessed the troubles of Southern agriculture first-hand. The strand of cotton that was best adapted to grow throughout the South—known as green-seed cotton—was high quality but contained many seeds within the fiber. These seeds needed to be removed before the raw cotton could be sent to textile mills. Whitney discovered that no effective machinery existed to remove the seeds, requiring laborers do the work by hand. The young man immediately set about to find a viable solution, recognizing that a machine that could minimize the workload of removing seeds would be hugely profitable. Whitney partnered with Phineas Miller, the manager of the plantation, in developing the machine. The two quickly produced a crude model of what became known as the cotton gin. This machine used combs to pull the seeds out and mesh to collect them while straining the finished fiber out.

In October 1793, Whitney wrote to Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson to apply for a patent for his invention. Jefferson was very intrigued by the device, replying, “As the state of Virginia, of which I am, carries on household manufactures of cotton to a great extent, as I also do myself, and one of our great embarrassments is the clearing the cotton of the seed, I feel a considerable interest in the success of your invention.” Whitney and Miller received a patent in March 1794 and developed a plan to travel to plantations to use the gin on farmers’ cotton in exchange for a portion of the completed supply. However, the cotton gin was not difficult to replicate, and many began to steal the design for themselves despite the patent. A variety of litigation cases followed as Whitney attempted to uphold his patent rights. However, a loophole in the laws at the time prevented the inventor from winning any of his court battles until 1807, at which point only a single year remained on his patent. He pleaded to Congress for a patent renewal, requesting in a letter to be “admitted to a more liberal participation with his fellow citizens, in the benefits of [the cotton gin],” but was denied on two separate occasions.

The cotton gin inadvertently increased demand for slavery in the South to meet the demands for the production of “King Cotton,” increasing sectional tensions in the country over the issue of human bondage. Whereas many of the founders believed that slavery would die a natural death because it was being restricted to the South where tobacco stripped the land of nutrients, the cotton gin helped breathe new life into the “peculiar institution.” Cotton and slavery spread to the new southern states in the early nineteenth century, and the scourge of human bondage in the country would exist until after the Civil War.

Joshua Schmid serves as a Program Analyst at the Bill of Rights Institute.

Click Here to have the NEWEST essay in this study emailed to your inbox every day!

Click Here to view the schedule of topics in our 90-Day Study on American History.

Join the discussion! Post your comments below.

Your feedback and insights are welcome.Feel free to contribute!