Senate History: Purpose Of The U.S. Senate, The “Cooling Factor” And “Sober Second Thought” – Guest Essayist: James Legee

LISTEN ON SOUNDCLOUD:

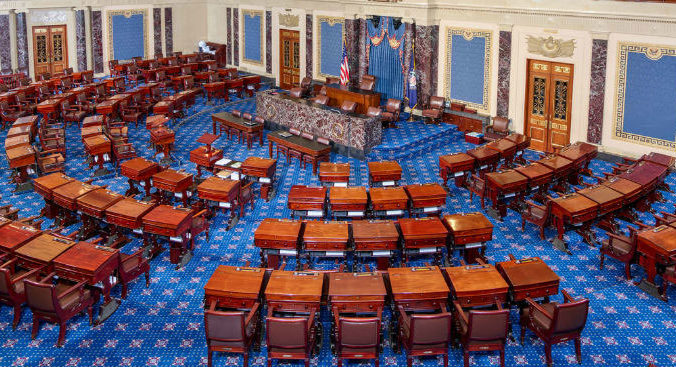

The Senate was intended to be the upper house of America’s Congress, a long-serving chamber of sober debate. Here, the passions of human nature, which history watched manifest into noble appeals to virtue and liberty as often as into the deplorable institution of slavery or the savagery of the French Revolution, were to be calmed and sober reason allowed to prevail.

The House of Representatives, apportioned by population and elected directly by the citizens of the United States, served to animate the preamble, giving voice to “We the People,” a key element of James Madison’s Virginia Plan. While Americans generally recall the Federalist victory of ratification of the 1787 Constitution and largely credit Madison, the debate in Philadelphia was far more complex. What came out of Philadelphia, and was ratified in the State Conventions, was a document and system of government far less democratic than Americans live under today.

With two representatives from each state who were selected by state legislatures, the Senate was intentionally designed to incorporate elements of the New Jersey plan. While this is reminiscent of the English Parliamentary system and certainly was a compromise, this was not merely Sherman’s attempt to appease smaller states. Rather, many of the founders had an abiding distrust of human nature. They feared the inflamed passions of citizens, whether the victims of circumstance, moved by a demagogue, or in error on a question of significance to the whole.

When we turn to the debate in Philadelphia itself, on May 31, 1787, the Convention was engaged over the appointment of members of what would become the House of Representatives. Roger Sherman of Connecticut and Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts were two of the first to speak. In Madison’s Notes of Debate, he records Sherman’s distrust, “Mr. Sherman opposed election by the people… The people, he said, should have as little to do as may be about the Government. They want information and are constantly liable to be misled.” Later on June 7, 1787 Sherman rose in support of John Dickinson’s proposal that state legislatures elect the Senate. Sherman contended that a “due harmony between the two Governments” arose from such a mode.

While Sherman highlights a distrust of the people and concern for the dual sovereignty of national and state governments, few spoke as vociferously against popular election than Elbridge Gerry. On the May 31 (again, discussing what became the House), Madison relates Gerry’s view that “The evils we experience [under the Confederation] flow from the excess of democracy. The people do not want virtue, but are the dupes of pretended patriots… [Gerry] said he had been too republican heretofore: he was still however republican, but had been taught by experience the danger of the levelling spirit.” Gerry later outlined a system in which the citizens would nominate people for the state legislature’s consideration.

Gerry rose again in strenuous opposition to direct election on June 7. Selection of senators could not be entrusted to the citizens, as “[t]he people have two great interests, the landed interest, and the commercial including the stockholders. To draw both branches [of Congress] from the people will leave no security to the latter interest; the people being chiefly composed of the landed interest, and erroneously supposing, that the other interests are adverse to it … Oppression will take place, and no free Government can last long where that is the case.” The Convention of 1787, of course, chose popular election for the House and state legislatures as the electors of the Senate.

Madison, too, was amenable to the concerns highlighted by Sherman, Gerry, and others. In Federalist 63 he wrote “As the cool and deliberate sense of the community ought in all governments … ultimately prevail over the views of its rulers; so there are particular moments in public affairs, when the people stimulated by some irregular passion, or some illicit advantage, or misled by the artful misrepresentations of interested men, may call for measures which they themselves will afterwards be the most ready to lament and condemn. In these critical moments, how salutary will be the interference of some temperate and respectable body of citizens, in order to check the misguided career, and to suspend the blow meditated by the people against themselves, until reason, justice and truth, can regain their authority over the public mind?” As Madison outlined in Federalist 51, government must first be obliged to control the governed. Thus, the founders built a redoubt against the harsher aspects of human nature in the form of the United States Senate. Of note, is that James Wilson of Pennsylvania was the only delegate to press for the direct election of not only the House, but the Senate and even the Presidency at the Philadelphia convention.

As time passed, however, public perception of the mode of Senate election came to be viewed as archaic, undemocratic, and highly corrupt. Figures as diverse as Andrew Johnson and William Jennings Bryan called for reform, to let the people select their senators.

Senator George Frisbie Hoar rose to answer the reformers. Hoar, the grandson of Roger Sherman, found himself one hundred years later in the same chamber Sherman helped to create and occupied. In an 1897 article in The Forum, “Has the Senate Degenerated?,” Hoar mounted a defense of the traditional Senate customs and mode of election, but began by acknowledging that the Senate was not a perfect institution. Hoar wrote “It is likewise true that the desire -of the people and the will of the Senate itself have been frequently baffled by using the power of lawful and constitutional debate [filibuster], not for the purpose of discussing practical questions which are expected to be brought to an issue, but for consuming time so as to prevent action.” Hoar further recognized that while the method of electing may seem antiquated, America had grown in territory, population, wealth, and prestige under the Constitution, that “although the subtleties of the question of currency and finance present themselves for solution as never before; although we have been brought so much nearer to foreign countries by steam and electricity, and our domestic commerce has multiplied many thousandfold. I believe the people, as a whole, are better, happier, more prosperous, than they ever were before; and I believe the two Houses of Congress represent what is best in the character of the people now as much as they ever did.”

Central to the success of the American system, for Hoar, was the preservation of the checks and balances embedded in the Constitution. The President and House represented the will of the American people, but the Senate was to preserve their better angels of our nature, for Hoar the Senate stood for the American people’s “…deliberate, permanent, settled desire,—its sober, second thought.”

James Legee, Visiting Lecturer, Framingham State University Department of Political Science

Click Here for the previous essay.

Click Here for the next essay.

Click Here to view the schedule of topics in our 90 Day Study on Congress.

One of the worst amendments was Amendment Seventeen that surrendered the method of voting for Senators to the popular will of the people. How far that Amendment strayed from what our Founding Fathers intended. Our Nation continues to suffer under this amendment.

The 17 Amendment resulted in two congressional bodies. This amendment needs to be repealed and the methodology of electing the

Senate must be improved for our nation to prosper.

The vision that the states have representation in the Senate is extremely important to preserve the individual states rights. By popular election of senators we have created two bodies of Congress in which neither represents the individual states rights.

This has led to the federal government having much more power than was ever intended to be given to it. And much less power to the individual states.

This one amendment as seriously damaged our republic.

Thank for another educational and thought provoking essay.

Sherman and Gerry had some interesting points. However, as with all us, our prognostications are not always accurate, they are decidedly wrong. The commercial interests have flourished quite well under both the State and people elected Senate.

I agree Hoar, it is lamentable that the filibuster degenerated from a sanctioned debate to a mere, pitiful ploy to prevent action.

Perhaps Barb is correct. Maybe we would have done better to leave the Senate to be elected by the States. Either way they appear to be a haughty hoard of untouchables.

“For though the LORD sit on high, He regards the lowly, but the haughty He knows from afar.”

Food for thought. Article V has a sunset clause on the union under the federal constitution. It is the clause that mandates that states shall never be deprived of their equal suffrage in the Senate without their consent. Several states NEVER ratified the 17th Amendment and Nevada explicitly voted against it rather than merely failing to ratify (not enough Yea votes) like other states. As a secret letter from James Madison was published in 1830 that described the states as “parties to the constitution” on the question of secession, it becomes clear that Article V suffrage of the states pertains to the state governments having representation in the Senate. Few realize that the 17th Amendment was an act of secession from the old 19th century regime just as the 2nd constitution of 1787 was an act of secession from the original Confederation of 1781. What then of the 50 states that never ratified the 17th Amendment, and Nevada that expressly called it unconstitutional?

The Senate was created by the founders to provide a check against what they feared would be “the fury of democracy” (as founding father Edmund Randolf put it). This “check” only made sense because senators would NOT be elected by the people. When the 17th gave that power to the people (the “mob” as the founders thought of them), the whole purpose for the Senate was rendered moot. Yet they needed the 17th despite this, primarily because of the Senate’s rampant corruption and dysfunction. To add insult to injury, the formalization of, and defacto use of the filibuster further erodes the founding principle of democracy on which the Constitution was based. In their effort to quell the “tyranny of the majority” we now have the tyranny of the minority. It’s almost like King George 2.0.

There is no remedy for this infected appendix. It needs to be removed. I’m a software engineer who is not squeamish about deleting dysfunctional code that serves no purpose anymore and is broken beyond repair. So even though this seems radical, I can tell you that bold action like this, especially when it is to evident, works. We just need the courage to do it. If we need to provide some sort of check against the House, then let’s design something for that which makes sense here in the 21st century. But this failed experiment we call the US Senate really needs to go.