Public Lands and the Federal Government’s “Duty to Dispose”

LISTEN ON SOUNDCLOUD:

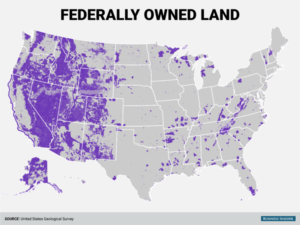

If one looks at a map of the United States, a map that differentiates land into who owns that land—privately owned, owned by state or local governments, or owned by the federal government, one might notice something incredibly interesting:

The further west one goes, the more land retained in ownership by the federal government. In fact, from the Rocky Mountains westward (essentially, any states that became states after the United States signed the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848), it is clear that, as a percentage of land, the United States government exercises enormous dominion:

And let us keep in mind that since this map is not to scale, Alaska’s size is under-represented—as seen here:

So, taking the first map and this one together, and understanding that Alaska is 60% federally-owned, it is clear that the federal government owns an enormous amount of land in the United States—much of it brought into the nation in the middle of the 19th Century.

But was the federal government ever intended to maintain permanent ownership of this land? Certainly, as the Constitution originally envisioned, the federal government was only supposed to own very discrete parcels of land, and retain ownership of that land for very specific purposes – as described in Article IV, Section 3, Clause 2.

The 5th Amendment also talks about the “taking” of private property (as differentiated from the out-and-out purchase of that land from other nations, or the gaining of territories via treaty), but is informative as to the why of land acquisition. Private property is to be “taken” for “public use” (and necessitating the both “due process” be accorded to the property owner, and “just compensation” be paid once the first two conditions are satisfied).

But the language about “public use” is informative – the federal government is only supposed to acquire lands for public uses (though that definition has shifted over time).

The central question is then raised: was it intended for the federal government to maintain permanent ownership or control over these lands, and did the federal government promise these western states that it would divest itself of these lands over time?

It is a question that has never been adequately answered—and no state has undertaken the necessary litigation to settle the underlying question.

What is clear is this: when states entered the Union (converting their status from federally-owned territories to become sovereign states), that happened via “Enabling Acts” negotiated by the territorial governments and then passed as legislation by Congress. In every state that entered the union after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, each enabling act contained some variation of language in which the state set-aside any claim to the title of “unappropriated public lands” within that state—and that the federal government would dispose of those lands.

Take the 1864 Nevada Enabling Act, for example. In Section 3, the state “disclaims” all right and title to these lands. But then, in Section 10, the agreement is as follows:

“That five percentum of the proceeds of the sales of all public lands lying within said state, which shall be sold by the United States subsequent to the admission of said state into the Union, after deducting all the expenses incident to the same, shall be paid to the said state…”

The “Shall” clause of that sentence makes it clear that the federal government undertook an obligation to dispose of those lands “subsequent to the admission” of Nevada into the Union (with Nevada gaining 5% of the proceeds from those sales).

Incidentally, the reason for this trade-off was a product of good public policy: these states wanted to be settled in the easiest and least chaotic manner possible. An essential element of that was ensuring that unappropriated public lands had “clear title”—a situation discussed at length in Peruvian economist and political scientist Hernando DeSoto’s seminal work, “The Mystery of Capital.”

In that work, DeSoto makes it clear that in order to have a stable and prosperous society, strong property rights are a fundamental necessity. A key aspect of that is the assurance title is clear—thus allowing property to be bought and sold with ease.

“Shall,” as the word was used in these enabling acts, had a very specific meaning especially at the time these enabling acts were written and passed. It was both a “command” on the part of the legislature, and it created a “duty” on the part of the federal government to engage in the activity evinced by the “shall” language.

And for a very long time, the federal government was in the business of fulfilling these obligations by disposing of these lands.

This changed with the passage of the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976 (FLPMA). FLPMA flipped this obligation on its head—and instead of the “duty to dispose,” the federal government now had an “obligation to retain” these public lands in perpetuity.

This has had enormous consequences for the United States… and the specific states which contain these enormous amounts of public lands, both from a fiscal perspective and from a general public policy perspective. This FLPMA represented a fundamental departure from the agreements upon which these states entered the Union.

Andrew Langer has served as President of the Institute for Liberty since 2008. IFL works on a variety of issues—promoting and protecting small business, fighting cronyism, tilting against the regulatory state. At the core of both is the desire to promote freedom and individual rights. Andrew has been involved in free-market and limited-government causes for nearly 20 years, has testified before Congress nearly two dozen times, and has spoken to audiences across the United States.

A nationally-recognized expert on the impact of regulation on business, Andrew is regularly called on to offer innovative solutions to the problem of burdensome regulatory state. Prior to coming to IFL, he was the principal regulatory affairs lobbyist for the National Federation of Independent Business, the nation’s largest small business association. He is also a nationally-recognized expert on the Constitution, especially issues surrounding private property rights, free speech, abuse of power, and the concentration of power in the federal executive branch.

In the Fall of 2019, Andrew joined the faculty of The College of William & Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia, the nation’s second-oldest college (his alma mater). He teaches on the regulatory state in the university’s Public Policy Program.

In addition to being IFL’s President, he also hosts a weekly show on WBAL NewsRadio 1090, Maryland’s largest news/talk station, appears regularly on television and other radio programs, and has guest-hosted on both nationally-syndicated terrestrial radio programs like “The Laura Ingraham Show” and shows on satellite radio.

In 2011, he was named one of Maryland’s “Influencers” by Campaigns and Elections magazine. He holds a Master’s Degree in Public Administration from Troy University and his degree from William & Mary is in International Relations. He may be reached via: www.IChooseLiberty.org, @Andrew_Langer & @IChooseLiberty on Twitter; https://www.facebook.com/LangerForLiberty; or https://www.facebook.com/AndrewLangerShow.

Join the discussion! Post your comments below.

Your feedback and insights are welcome.Feel free to contribute!