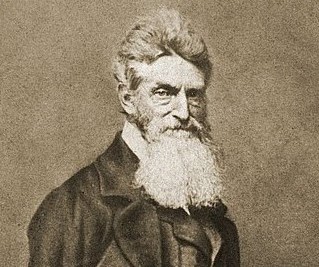

October 16-18, 1859: The John Brown Raid, Catalyst for Civil War

On the evening of Oct. 16, 1859, John Brown and his raiders unleashed 36 hours of terror on the federal armory in Harpers Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia).

Brown’s raid marked a cataclysmic moment of change for America and the world. It ranks up there with Sept. 11, the Dec. 7, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, and the shots fired on Lexington Common and Concord Bridge during the momentous day of April 19, 1775. Each of these days marked a point when there was no turning back. Contributing events may have been prologue, but once these fateful days took place, America was forever changed.

Americans at the time knew that the raid was not the isolated work of a madman. Brown was the well-financed and supported “point of the lance” for the abolition movement.

He was a major figure among the leading abolitionists and intellectuals of the time. This included Gerrit Smith, the second wealthiest man in America and business partner of Cornelius Vanderbilt. Among other ventures, Smith was a patron of Oberlin College, where Brown’s father served as a trustee. Thus was born a 20-year friendship.

Through Smith, Brown moved among America’s elite, conversing with Henry David Thoreau, Ralph Waldo Emerson, journalists, religious leaders and politicians.

Early on, Brown deeply believed that the only way to end slavery was through armed rebellion. His vision was to create a southern portal for the Underground Railway in the Blue Ridge Mountains.

The plan was to raise a small force and attack the armory in Harpers Ferry. There Brown would obtain additional weapons and then move into the Blue Ridge to establish his mountain sanctuary for escaping slaves.

Brown anticipated having escaped slaves swell his rebellious ranks and protect his sanctuary. He planned to acquire hundreds of metal tipped pikes as the weapon of choice.

The idea of openly rebelling against slavery was an extreme position in the 1850s. Abolitionist leaders felt slavery would either become economically obsolete or had faith that their editorials would shame the federal government to end the practice.

For years Brown remained the lone radical voice in the elite salons of New York and Boston. He looked destined to remain on the fringes of the anti-slavery movement when a series of events shook the activists’ trust in working within the system and shifted sentiment toward Brown’s solution.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 forced local public officials in free states to help recover escaped slaves. The federally sanctioned intrusion of slavery into the North began tipping the scales in favor of Brown’s agenda.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 destroyed decades of carefully crafted compromises that limited slavery’s westward expansion. The Act ignited a regional civil war as pro-slavery and anti-slavery settlers fought each other prior to a referendum on the state’s status – slave or free. Smith enlisted the help of several of the more active abolitionists to underwrite Brown’s guerilla war against slavery in Kansas in 1856-57. This group, including some of America’s leading intellectuals, went on to become the Secret Six, who pledged to help Brown with his raid.

The Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision in 1857, and its striking down of Wisconsin’s opposition to the Fugitive Slave Act in March 1859, set the Secret Six and Brown on their collision course with Harpers Ferry.

Today, Harpers Ferry is a scenic town of 300 people, but in 1859 it was one of the largest industrial complexes south of the Mason Dixon Line. The Federal Armory and Rifle Works were global centers of industrial innovation and invention. The mass production of interchangeable parts, the foundation of the modern industrial era, was perfected along the banks of the Potomac and Shenandoah Rivers.

Brown moved into the Harpers Ferry area on July 3, 1859, establishing his base at the Kennedy Farm a few miles north in Maryland. The broader abolitionist movement remained divided about an armed struggle. During August 19-21, 1859, a unique debate occurred. At a quarry outside Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, Frederick Douglass and Brown spent hours debating whether anyone had a moral obligation to take up arms against slavery. Douglass refused to join Brown but remained silent about the raid. Douglass’ aide, Shields Green, was so moved by Brown’s argument, he joined Brown on the raid, was captured, tried, and executed.

The American Civil War began the moment Brown and his men walked across the B&O Railroad Bridge and entered Harpers Ferry late on the evening of October 16, 1859. Brown’s raiders secured the bridges and the armories as planned. Hostages were collected from surrounding plantations, including Col. Lewis W. Washington, great grandnephew of George Washington. A wagon filled with “slave pikes” was brought into town. Brown planned to arm freed slaves with the pikes assuming they had little experience with firearms.

As Brown and his small force waited for additional raiders with wagons to remove the federal weapons, local militia units arrived and blocked their escape. Militia soldiers and armed townspeople methodically killed Brown’s raiders, who were arrayed throughout the industrial complexes.

Eventually, the surviving raiders and their hostages retreated into the Armory’s Fire Engine House for their last stand. Robert E. Lee and a detachment of U.S. Marines from Washington, D.C. arrived on October 18. The Marines stormed the Engine House, killing or capturing Brown and his remaining men, and freeing the hostages. The raid was over.

Brown survived the raid. His trial became a national sensation as he chose to save his cause instead of himself. Brown rejected an insanity plea in favor of placing slavery on trial. His testimony, and subsequent newspaper interviews while awaiting execution on Dec. 2, 1859, created a fundamental emotional and political divide across America that made civil war inevitable.

Fearing that abolitionists were planning additional raids or slave revolts, communities across the South formed their own militias and readied for war. There was no going back to pre-October America.

Edmund Ruffin, one of Virginia’s most vocal pro-slavery and pro-secession leaders, acquired several of Brown’s “slave pikes.” He sent them to the governors of slave-holding states, each labeled “Sample of the favors designed for us by our Northern Brethren.” Many of the slave pikes were publicly displayed in southern state capitols, further inflaming regional emotions.

On April 12, 1861, Ruffin lit the fuse on the first cannon fired at Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina. The real fuse had been lit months earlier by Brown at Harpers Ferry.

Scot Faulkner is Vice President of the George Washington Institute of Living Ethics at Shepherd University. He was the Chief Administrative Officer of the U.S. House of Representatives. Earlier, he served on the White House staff. Faulkner provides political commentary for ABC News Australia, Newsmax, and CitizenOversight. He earned a Master’s in Public Administration from American University, and a BA in Government & History from Lawrence University, with studies in comparative government at the London School of Economics and Georgetown University.

Click Here to have the NEWEST essay in this study emailed to your inbox every day!

Click Here to view the schedule of topics in our 90-Day Study on American History.

Join the discussion! Post your comments below.

Your feedback and insights are welcome.Feel free to contribute!