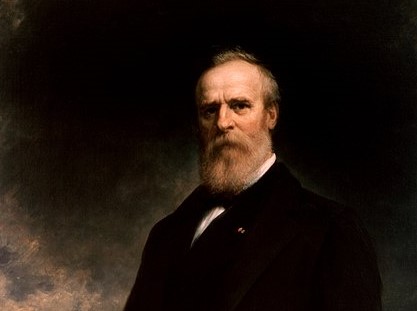

March 2, 1877: The President Rutherford B. Hayes Electoral Compromise and End of Southern Reconstruction

Usually, breaking down history into chapters requires imposing arbitrary separations. Every once in a while, though, the divisions are clear and real, providing a hard-stop in the action that only makes sense against the backdrop of what it concludes, even if it explains what follows.

For reasons having next-to-nothing to do with the actual candidates,[1] the Presidential election of 1876 provided that kind of page-break in American history. It came on the heels of the Grant Presidency, during which the victor of Vicksburg and Appomattox sought to fulfill the Union’s commitments from the war (including those embodied in the post-war Constitutional Amendments) and encountered unprecedented resistance. It saw that resistance taken to a whole new level, which threw the election results into chaos and created a Constitutional crisis. And by the time Congress had extricated itself from that, they had fixed the immediate mess only by creating a much larger, much more costly, much longer lasting one.

Promises Made

To understand the transition, we need to start with the backdrop.

Jump back to April 1865. General Ulysses S. Grant takes Richmond, the Confederate capitol. The Confederate government collapses in retreat, with its Cabinet going its separate ways.[2] Before it does, Confederate President Jefferson Davis issues his final order to General Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia: keep fighting! He tells Lee to take his troops into the countryside, fade into a guerrilla force, and fight on, making governance impossible. Lee, of course, refuses and surrenders at Appomattox Courthouse. A celebrating Abraham Lincoln takes a night off for a play, where a Southern sympathizer from Maryland murders him.[3] Before his passing, Abraham Lincoln had freed the slaves and won the war (in part, thanks to the help of the freedmen who had joined the North’s army), so saving the Union. His assassination signified a major theme of the next decade: some’s refusal to accept the war’s results left them willing to cast aside the rule of law and employ political violence to resist the establishment of new norms.

Leaving our flashback: Andrew Johnson succeeded Lincoln in office, but in nothing else. Super-majorities in both the House and Senate hated him and his policies and established a series of precedents enhancing Congressional power, even while failing to establish the one they wanted most.[4] Before his exit from the White House, despite Johnson’s opposition: (a) the States had ratified the Thirteenth Amendment (banning slavery); (b) Congress had passed the first Civil Rights Act (in 1866, over his veto); (c) Congress had proposed and the States had ratified the Fourteenth Amendment (“constitutionalizing” the Civil Rights Act of 1866 by: (i) creating federal citizenship for all born in our territory; (ii) barring states from “abridg[ing] the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States[;]” (iii) altering the representation formula for states in Congress and the electoral college, and (iv) guaranteeing the equal protection of the laws); and (d) in the final days of his term, Congress formally proposed the Fifteenth Amendment (barring states from denying or abridging the right to vote of citizens of the United States “on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”).

Notice how that progression, at each stage, was made necessary by the resistance of some Southerners to what preceded it. Ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery? Bedford Forrest, a low-ranking Confederate General, responded by reversing Lee’s April decision: in December 1865, he founded the Ku Klux Klan (effectively, Confederate forces reborn) to wage the clandestine war against the U.S. government and the former slaves it had freed, which Lee refused to fight. Their efforts (and, after Johnson recognized them as governments, the efforts of the Southern states to recreate slavery under another name) triggered passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and the Fourteenth Amendment. Southern states nonetheless continued to disenfranchise black Americans. So, Congress passed the Fifteenth Amendment to stop them. Each step required the next.

And the next step saw America, at its first chance, turn to its greatest hero, Ulysses S. Grant, to replace Johnson with someone who would put the White House on the side of fulfilling Lincoln’s promises. Grant tried to do so. He (convinced Congress to authorize and then) created the Department of Justice; he backed, signed into law, and had DOJ vigorously prosecute violations of the Enforcement Act of 1870 (banning the Klan and, more generally, the domestic terrorism it pioneered using to prevent black people from voting), the Enforcement Act of 1871 (allowing federal oversight of elections, where requested), and the Ku Klux Klan Act (criminalizing the Klan’s favorite tactics and making state officials who denied Americans either their civil rights or the equal protection of law personally liable for damages). He readmitted to the Union the last states of the old Confederacy still under military government, while conditioning readmission on their recognition of the equality before the law of all U.S. citizens. Eventually, he signed into law the Civil Rights Act of 1875, guarantying all Americans access to all public accommodations.

And over the course of Grant’s Presidency, these policies bore fruit. Historically black colleges and universities sprang up. America’s newly enfranchised freedmen and their white coalition partners elected governments in ten (10) states of the former Confederacy. These governments ratified new state constitutions and created their states’ first public schools. They saw black Americans serve in office in significant numbers for the first time (including America’s first black Congressmen and Senators and, in P.B.S. Pinchback, its first black Governor).

Gathering Clouds

But that wasn’t the whole story.

While the Grant Administration succeeded in breaking the back of the Klan, the grind of entering a second decade of military tours in the South shifted enough political power in the North to slowly sap support for continued, vigorous, federal action defending the rights of black Southerners. And less centralized terrorist forces functioned with increasing effectiveness. In 1872, in conjunction with a state election marred by thuggery and fraud, one such “militia” massacred an untold number of victims in Colfax, Louisiana. Federal prosecution of the perpetrators foundered when the Supreme Court gutted the Enforcement Acts as beyond Congress’s power to enact.

That led to more such “militias” often openly referring to themselves as “the military arm of the Democratic Party” flowering across the country. And their increasingly brazen attacks on black voters and their white allies allowed those styling themselves “Redeemers” of the region to replace, one by one, the freely elected governments of Reconstruction first in Louisiana, then in Mississippi, then in South Carolina… with governments expressly dedicated to restoring the racial caste system. “Pitchfork” Ben Tillman, the leader of a parallel massacre of black Union army veterans living in Hamburg, South Carolina, used his resulting notoriety to launch a political career spanning decades. Eventually, he reached both the governor’s mansion and the U.S. Senate, along the way, becoming the father of America’s gun-control laws, because it was easier to terrorize and disenfranchise the disarmed.

By 1876, with such “militias” enjoying a clear playbook and, in places, support from their state governments, the stage was set for massive fraud and duress trying to swing a presidential election. Attacks on black voters, and their allies, intended to prevent a substantial percentage of the electorate from voting, unfolded on a regional scale. South Carolina, while pursuing such illegal terror, simultaneously claimed to have counted more ballots than it had registered voters. The electoral vote count it eventually sent to the Senate was certified by no one – that for Louisiana was certified by a gubernatorial candidate holding no office. Meanwhile, Oregon sent two different sets of electoral votes: one certified by the Secretary of State, the other certified by the Governor, cast for two different Presidential candidates.

The Mess

The Twelfth Amendment requires states’ electors to: (a) meet; (b) cast their votes for the President and Vice President; (c) compile a list of vote-recipients for each (to be signed by the electors and certified); and (d) send the sealed list to the U.S. Senate (to the attention of the President of the Senate). It then requires the President of the Senate to open the sealed lists in the presence of the House and Senate to count the votes.

Normally, the President of the Senate is the Vice President. But Grant’s Vice President, Henry Wilson, had died in 1875 and the Twenty-Fifth Amendment’s mechanism to fill a Vice Presidential vacancy was still almost a century away. That left, in 1876, the Senate’s President Pro Tempore, Thomas W. Ferry (R-MI) to serve as the acting President of the Senate. But given the muddled state of the records sent to the Senate, Senate Democrats did not trust Ferry to play this role. Since the filibuster was well established by the 1870s, the Senate could do nothing without their acquiescence. More, they could point to Johnson-Administration precedents enhancing Congressional authority to demand that resolution of disputed electoral votes be reached jointly by both chambers of Congress, which they preferred, because Democrats had taken a majority of the lower House in 1874.

No one agreed which votes to count. No one agreed who could count them. And the difference between sets was enough to deliver the majority of the electoral college to either major party’s nominees for the Presidency and Vice Presidency. And all of this came at the conclusion of an election already marred by large-scale, partisan violence.

Swapping Messes

It took the Congress months to find its way out of this morass. Eventually, it did so through an unwritten deal. On March 2, 1877, Congress declared Ohio Republican, Rutherford B. Hayes, President of the United States over Democratic candidate Samuel J. Tilden of New York. Hayes, in turn, embraced so-called “Home Rule,” removing all troops from the old Confederacy and halting the federal government’s efforts to either enforce the Civil Rights Acts or make real the promises of the post-war Constitutional Amendments.

With the commitments of Reconstruction abandoned, the “Redeemers” promptly completed their “Redemption” of the South from freely, lawfully elected governments. They rewrote state constitutions, broadly disenfranchised those promised the vote by the Fifteenth Amendment, and established the whole Jim-Crow structure that ignored (really, made a mockery of) the Fourteenth Amendment’s guaranties.

Congress solved the short-term problem by creating a larger, structural one that would linger for a century.

Dan Morenoff is Executive Director of The Equal Voting Rights Institute.

Click Here to have the NEWEST essay in this study emailed to your inbox every day!

Click Here to view the schedule of topics in our 90-Day Study on American History.

[1] Rutherford B. Hayes, the Republican nominee, was the Governor of Ohio at the time who had served in the Union army as a Brigadier General; Samuel J. Tilden, the Democratic nominee, was the Governor of New York at the time, and earlier had been among the most prominent anti-slavery, pro-union Democrats to remain in the party in 1860. Indeed, in 1848, Tilden was a founder of Martin Van Buren’s Free Soil Party, who attacked the Whigs (which Hayes then supported) as too supportive of slave-power.

[2] CSA President Jefferson Davis broke West, with the intention of reaching Texas and Arkansas (both unoccupied by the Union and continuing to claim authority from that rump-Confederacy). His French-speaking Louisianan Secretary of State Judah P. Benjamin broke South, pretending to be a lost immigrant peddler as he wound his way to Florida, then took a raft to Cuba as a refugee. He won asylum, there, with the British embassy and eventually rode to London with the protection of the British Navy – alone among leading Confederates, Benjamin had a successful Second Act, in which he became a leading British lawyer and author of the world’s leading treatise on international taxation.

[3] To this day, it is unclear to what degree John Wilkes Booth was a Confederate operative. He certainly spied for the CSA. No correspondence survives to answer whether his assassination of Lincoln was a pre-planned CSA operation or freelancing after Richmond’s fall.

[4] He survived impeachment by a single vote.

Join the discussion! Post your comments below.

Your feedback and insights are welcome.Feel free to contribute!