Funding States and Cities: How Dollars Work (Part 2)

LISTEN ON SOUNDCLOUD:

Intergovernmental Finance

Every nickel spent by a state or local government ultimately comes from the pockets of some private entity, but often public monies are exchanged between governments. Intergovernmental transfer payments account for 23 percent of all money spent by state and local governments.

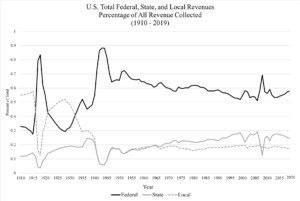

Most intergovernmental transfer payments point “downwards” in the federal system, moving from larger governments to ones of smaller size. The federal government delivered $621-billion to the various states in 2016, and state governments sent $524-billion to various localities in that same year.[1] Overtime, intergovernmental payments have grown as a share of state and local government revenues — a trend we will evaluate in the next essay — and the federal government has even come to make direct payments to localities in some specific instances.

Most forms of intergovernmental revenue take the form of grants — direct payments to a state or local government agency, with a specific purpose outlined by the grantee. The federal government, for example, sends billions of dollars it collects to the states for the purpose of constructing and maintaining highways. Likewise, state governments send some tax revenue it collects to localities for funding public health programs. The federal government even sends money to the states that the states then divide up and send to the localities.

Intergovernmental payments can be rigidly formulaic — a set number of dollars for a set number of persons — that treat governments of similar size equally. Payments can also be re-distributive, taking tax dollars from one political community and giving it to another. Most local school systems, for instance, fund their expenses through property taxes raised in the local community they serve. Increasingly, however, state governments re-distribute some of those monies, taking local revenues from towns, counties, and cities with higher property values, and sending it to communities with lower property values, and, consequently, lower revenues.

Beyond its redistributive effects, larger governments tend to send revenues to governments of smaller size out of recognition that money can be spent more effectively at the local level than a state-wide or national level. In fact, grants and other types of intergovernmental spending account for over 17% of all federal monies that the Congress appropriates each year.[2] As such, much of what the federal government does is, in fact, done by governments of smaller size. But in exchanging monies, intergovernmental transfers are one way in which larger governments set new restrictions on smaller governments, sometimes with little relevance to the funding purpose. For example, in 1984, Congress passed a law requiring states to raise the minimum drinking age as a condition for receiving its share of federal highway funds. More recently, the federal government imposed requirements on local public schools to develop and administer specific tests for all enrolled students: The 2001 law, No Child Left Behind. As a result, if local governments fail to follow federal guidelines, they risk losing all federal grant payments for education, which account for just 10% of all local education expenditures.

Public Finance in a Federal System

The revenue decisions reached by representatives within each government set hard constraints on the other powers and actions of governing officials, but taxing decisions also affect how people behave, even when there is no specific government program.

For example, many cities have recently imposed a tax on plastic bags, like the type often used at convenience stores and supermarkets. The stated goal is not so much to raise money (although most of the time these taxes fund specific environmental programs) as to discourage the use of plastic bags. States also experiment with other types of “excise” taxes — fees placed on specific goods — to discourage tobacco, liquor, and even soda consumption; these often have the more politically-palatable name, “sin tax.” However, in a federal system where one government’s rates differ from a nearby government’s, such taxes might simply distort behaviors, rather than end them. New York State, for example, has the highest excise tax on cigarettes: $4.35 on every pack sold in its borders. Half a day’s drive away in Virginia, the state levies just 30-cents per pack. It is not a coincidence that an estimated 56% of all cigarettes smoked in New York are currently smuggled in from out-of-state.[3]

As previously mentioned, when governments of smaller scale levy certain types of taxes, the economic incidence paid by taxpayers might better reflect the actual economic circumstance of that community. This is not always the case. The United States is a very large country, and when the national government levies taxes, particularly on income, it treats each citizen in the country equally, regardless of where they live. A person making $40,000 in Alabama pays the same marginal tax-rate as a Californian who makes the same amount, but who pays more in state and local taxes, and spends a proportionately higher amount of that $40,000 on rent, food, and transportation, due to variation in cost-of-living. Consequently, citizens in some states pay more to the federal government than they get back in government goods and services — an issue known as a state’s relative balance of payments. Residents of New Jersey have the worst balance of payments — receiving just 74-cents back from the federal government for every dollar they send — while residents of New Mexico get back $2.21 for every dollar they pay in taxes.[4]

As a closing note: one of the most consequential political developments in American history has been the legal restrictions citizens have placed on state and local governments for amassing public debt. It was routine in the 1800s for cities, in particular, to go bankrupt. At the turn of the 20th century, state governments limited the ability of municipalities to run annual deficits, but, with time, states began to spend more than they took in. Through ballot initiatives and legislative action, citizens enacted state-constitutional amendments that required balanced budgets for their governments. As such, the U.S. federal government is the only government that can formally spend more money than it raises.

These restrictions further complicate the way states and localities fund themselves, especially during hard times. For instance, property and sales taxes are highly “elastic,” which means that when the overall economy slows down, revenues can quickly fall. Debt restrictions and high elasticity create a peculiar circumstance, and often increase state and local demand for intergovernmental transfers. Following the 2007-2008 recession, which depressed home prices (decreasing local property tax revenues) and slowed consumer spending (decreasing state sales tax revenues), the federal government had to increase its own debt levels in order to finance state and local government services. Of the $787 billion Congress authorized as a part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, or “stimulus,” more than a third was sent directly to state and local governments.[5]

States and cities can also sidestep legal prohibitions and gather additional funds by issuing bonds for “capital improvements” or by dipping into reserved funds, such as a state employee pension fund. State and local governments, collectively, hold about $3-trillion in public debt. Many pension funds have remained unbalanced for decades and the solvency of these accounts is one of the largest financing hurdles state and local governments will have to overcome as the American population grows older, and the “Baby Boomer” generation retires.

All of these developments notwithstanding, the constitutional foundation for America’s system of public finance is largely unchanged. The complex arrangement of varying tax sources, rates, and redistribution is the hallmark of a federal system that empowers multiple governments to act simultaneously within the same political jurisdiction. In the next essay, we will look more closely at the argument for why federalism — and independent budgetary authority — creates a more robust system of public finance, even if it appears to be more complicated and unwieldly. This is not to say that the modern system is perfect, and so we will also evaluate several leading proposals to fix the country’s federated financial system.

Nicholas Jacobs is a Faculty Research Associate in the School of Civic and Economic Thought and Leadership at Arizona State University, where he also serves as the assistant project director of the Living Repository of the Arizona Constitution. He has published numerous scholarly articles on intergovernmental politics, American political history, and the American presidency.

Click Here to have the NEWEST essay in this study emailed to your inbox every day!

Click Here to view the schedule of topics in our 90 Day Study on Congress.

[1] Data on intergovernmental transfers, including the data graphed in Figure 2, was retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/. All dollar amounts are pegged to their corresponding calendar year, and are not seasonally adjusted. Last accessed, April 11, 2017.

[2] Congressional Budget Office. 2013. “Federal Grants to State and Local Governments.” Government Printing Office, 5 March. Retrieved on March 14, 2018 (https://www.cbo.gov/publication/43967).

[3] Scott Drenkard. 2017. “Cigarette Taxes and Cigarette Smuggling by State, 2015.” Tax Foundation. URL: https://taxfoundation.org/cigarette-tax-cigarette-smuggling-2015/

[4] Rockefeller Institute of Government. 2017. Giving or Getting? New York’s Balance of Payments with the Federal Government. State University of New York. URL: https://rockinst.org/issue-area/giving-getting-new-yorks-balance-payments-federal-government-2/

[5] Timothy Conlan and Paul Posner. 2016. “American Federalism in an Era of Partisan Polarization: The Intergovernmental Paradox of Obama’s ‘New Nationalism.'” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 46 (3): 281-307.

Join the discussion! Post your comments below.

Your feedback and insights are welcome.Feel free to contribute!