February 27, 1860: Abraham Lincoln Delivers His Cooper Union Address

On the evening of February 27, 1860, New Yorkers paid an exorbitant twenty-five cents to listen to a commonplace politician from some prairie state. The man had a reputation as a storyteller extraordinaire. Everyone expected to be entertained; few took the speaker seriously as a presidential candidate. Abraham Lincoln had earned a modicum of fame due to his debates with Senator Stephen Douglas two years previously, but he had lost that race and most believed the fledgling Republican Party would never nominate a loser. In fact, many wondered how this roughhewn storyteller wangled an invitation to a lecture series meant to expose serious candidates to the New York elite? Homespun yarns might draw crowds in the bucolic West, but New York City demanded a more elevated style of speechmaking.

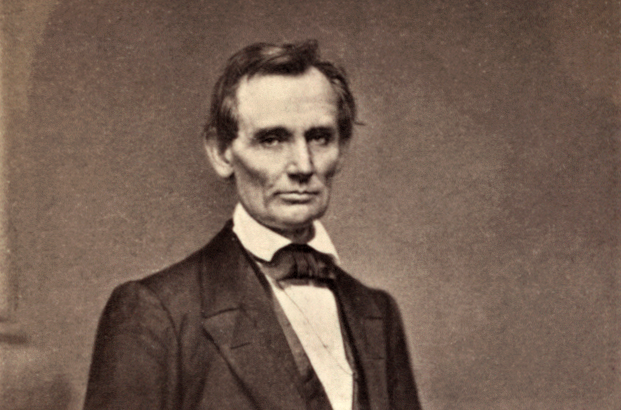

The Republican Party was new and had failed in running John C. Frémont, a national hero, for president in 1856. Lincoln’s chances of ascending to the presidency under the Republican banner were slight. Lincoln, of course, had other plans. That afternoon, he had his photograph taken by Mathew Brady, and he intended his evening speech to be historic. It was. Lincoln often said that the Brady’s photograph and his Cooper Union address propelled him to the presidency.

What was so great about his speech at the Cooper Union? It was earth-moving because it was highly unusual. It was a call for his party to stand on principle—God’s principles, the Founders’ principles, and the founding principle of the Republican Party—the abolition of slavery.

Lincoln wanted to debunk the Democrats’ claim that the Founders would have supported the extension of slavery into the territories, so he presented a scholarly review of the voting records of the Constitution’s thirty-nine signers, showing that twenty-one of them had voted for bills restricting slavery in territories, and sixteen had left no record. Only two had made votes that supported the Democrats’ contention.

His speech had started slow, but as it picked up momentum, the energy in the hall lifted until the excited audience waited on the edge of their seats for the next opportunity to clap, yell, and bang out a rhythm with their shoes. Lincoln gave them plenty of opportunities. Below is a highly abridged selection from his speech.

We hear that you will not abide the election of a Republican president! In that event, you say you will destroy the Union; and then, you say, the great crime of having destroyed it will be upon us!

That is cool. A highwayman holds a pistol to my ear, and mutters through his teeth, ‘Stand and deliver, or I shall kill you and then you will be a murderer!’

What the robber demands of me—my money—is my own; and I have a clear right to keep it; but my vote is also my own; and the threat of death to me to extort my money and the threat to destroy the Union to extort my vote can scarcely be distinguished.

What will convince slaveholders that we do not threaten their property? This and this only: cease to call slavery wrong and join them in calling it right. Silence alone will not be tolerated—we must place ourselves avowedly with them. We must suppress all declarations that slavery is wrong, whether made in politics, in presses, in pulpits, or in private. We must arrest and return their fugitive slaves with greedy pleasure. The whole atmosphere must be disinfected from all taint of opposition to slavery before they will cease to believe that all their troubles proceed from us.

All they ask, we can grant, if we think slavery right. All we ask, they can grant if they think it wrong.

Right and wrong is the precise fact upon which depends the whole controversy.

Thinking it wrong, as we do, can we yield? Can we cast our votes with their view and against our own? In view of our moral, social, and political responsibilities, can we do this?”

Let us not grope for some middle ground between right and wrong. Let us not search in vain for a policy of don’t care on a question about which we do care. Nor let us be frightened by threats of destruction to the government.”

Prolonged applause kept Lincoln silent for several minutes before delivering his final sentence.

“Let us have faith that right makes might, and in that faith, let us, to the end, dare to do our duty as we understand it!”

When Lincoln stepped back from the podium, the Cooper Union Great Hall exploded with noise and motion. Everybody stood. The staid New York audience cheered, clapped, and stomped their feet. Many waved handkerchiefs and hats.

Great leaders speak and act on principle. People will not only follow a principled leader; they will labor mightily in a principled cause.

Abraham Lincoln went on to win the Republican nomination, the presidency, the Civil War, and the abolition of slavery.

Click here to read the text of Abraham Lincoln’s Address At Cooper Union.

(To learn more, I recommend Lincoln at Cooper Union by Harold Holzer.)

James D. Best, author of Tempest at Dawn, a novel about the 1787 Constitutional Convention, Principled Action, Lessons From the Origins of the American Republic, and the Steve Dancy Tales.

Click Here to have the NEWEST essay in this study emailed to your inbox every day!

Click Here to view the schedule of topics in our 90-Day Study on American History.

Join the discussion! Post your comments below.

Your feedback and insights are welcome.Feel free to contribute!