February 22, 1819: The Adams-Onis Treaty Cedes Florida to the United States

February 22, 1819, was, John Quincy Adams recorded in his diary, “perhaps the most important day of my life.”[1] On that day, the United States finalized a momentous treaty with Spain that acquired Florida for the United States and settled a border with Spain’s North American provinces that reached across the continent to give the United States a piece of Oregon on the Pacific Ocean.

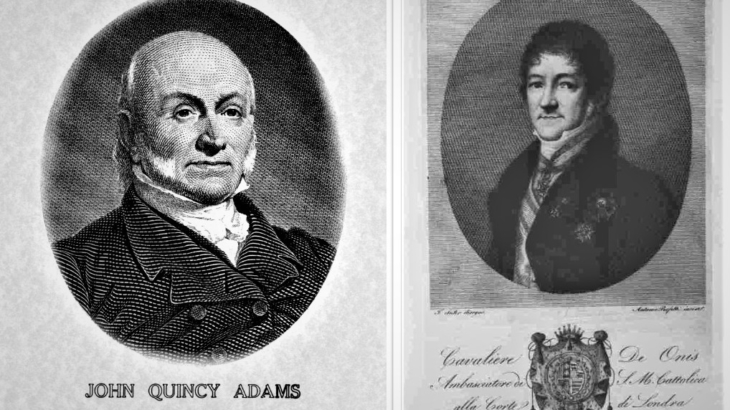

The agreement was known officially as the Treaty of Amity, Settlement, and Limits Between the United States of America and His Catholic Majesty.[2] Today, it’s more commonly called the Transcontinental Treaty, to emphasize its geographic scope, or it’s known as the Adams–Onís Treaty, after its two architects, Secretary of State Adams and Spanish minister plenipotentiary Luis de Onís.[3]

Adams would have preferred the last title. Self-pitying and often depressed, he feared his role would “never be known to the public—and, if ever known, will be soon and easily forgotten.”[4]

Adams and Onís negotiated the final agreement, but the issues between their two nations ranged back to the earliest days of the American republic.

One source of discord was the border. Where, exactly, did it lie?

The Treaty of Paris that ended the American Revolution promised the United States British territory west to the Mississippi River and south to the 31st parallel (the north–south border between Alabama and the Florida panhandle today).[5]

Spain, though not a formal U.S. ally, fought against Britain in the war as an ally of France. In North America, fighting on the winning side brought Spain the British colonies of East and West Florida. The two Floridas were analogous to the modern state, but somewhat bigger as the panhandle extended West Florida along the Gulf of Mexico to the Mississippi River. On the northern side, Spain claimed the Floridas were even larger as it did not recognize the 31st parallel as the proper boundary.

In 1795, Spain acquiesced to the American definition of its border with Florida in the Treaty of San Lorenzo (also called Pinckney’s Treaty). But new problems erupted eight years later when the United States acquired the Louisiana territory from France.[6]

The Purchase treaty was maddeningly vague on just what “Louisiana” was. Rather than stipulating geographic features like rivers—things that might appear on both a map and in reality—the document defined the land to be transferred only by reference to the Treaty of San Ildefonso in which Spain had ceded Louisiana back to France in 1800.[7]

With Louisiana moved from France to Spain, back to France, and then to the United States, it’s little wonder no one could say what “Louisiana” really was.

For their part, U.S. policymakers insisted they had purchased West Florida from the Mississippi River east to the Perdido River (the modern border between Alabama and Florida) as well as a chunk of Texas from the Mississippi to the Rio Grande.

Spain countered that no, Louisiana was never that big. In the gulf region, Louisiana was only ever a sliver between the Mississippi River in the east and the midpoint between the Mermentau and Calcasieu Rivers in the west (not far from the border between modern Louisiana and Texas). Everything else was Spanish.

Another category of contention revolved around money. The U.S. government felt Spain owed U.S. citizens compensation because of two Spanish violations of American rights.

The first kind of violation happened in the 1790s, and like the land squabbles, it involved Spain’s relationship with France and the geopolitics of European war. Some American ships attempting to trade with Britain had been seized by French privateers and were then taken to Spanish ports to be condemned as prize of war by a friendly admiralty court. Since the United States declared its neutrality in the war, U.S. leaders said Spain had committed spoliations—unlawful destruction of a neutral’s property—and should make restitution to the American merchants.

The second kind of violation occurred in 1802 when Spain, which controlled New Orleans, prevented American merchants from selling their goods in the city, a right won for Americans trading down the Mississippi River by the Treaty of San Lorenzo. American merchants stuck with goods they couldn’t sell demanded that Spain make them whole.

Spain and the United States attempted to reconcile on several occasions in the following years. But no agreement survived Napoleon’s shifting ambitions, the emerging Spanish American push for independence, and the fading of Spain’s position as an imperial power.

France’s 1808 invasion of Spain touched off a crisis for the Spanish empire. Napoleon vanquished the king, installed his brother Joseph on the throne, and inspired a resistance government to form in Spain and independence movements to rise up in the Americas to fight against both French and Spanish rule.

The United States broke off negotiations with Spain as a result. Though Luis de Onís lived in Philadelphia, President James Madison kept him at arm’s length. Madison didn’t want the United States appearing to take sides in the Spanish resistance government’s battle with Napoleon or look like it was playing favorites between Spain and its rebelling colonies.

In 1814, King Fernando VII regained the Spanish crown in the wake of Napoleon’s defeat. Relations between the United States and Spain stayed chilly, however. President Madison didn’t trust Onís, who he suspected of conspiring with Britain during the War of 1812, but more substantially, both nations believed their bargaining power would improve with time. As a consequence, both sides delayed negotiations.

In 1817, a new administration took office, with James Monroe as president and Adams as Secretary of State. The delays continued.[8]

Onís was officially received by Monroe. Talks began but the delays continued. Adams complained about his futile meetings with Onís, who, he said, “beat about the bush” and failed to “make any propositions at all.”[9]

Then, suddenly in 1818, two developments broke open negotiations and quickly produced a treaty.

First, General Andrew Jackson invaded Spanish Florida. Tasked to secure the Georgia–Florida border against Indian attacks and prevent slaves from running away, Jackson exceeded his orders, captured two Spanish forts, and executed two British subjects for assisting Natives. Following tense discussions inside the administration, Monroe decided to back Jackson. Onís, fearing the United States might seize Florida outright, backed down. A treaty sooner rather than later looked good.

Second, Spain found its hopes of European support for retaking its American colonies frustrated. Meeting at the Congress of Aix-la-Chapelle, Fernando’s fellow kings refused to help restore his empire. Spain was on its own in the Americas. A deal with the United States was imperative.

The treaty terms settled both the border and compensation issues. The United States received Florida, its top priority, and access to the Pacific via Oregon, its second concern.

Spain got the Texas border it wanted, and the United States agreed to take responsibility for paying the claims of U.S. citizens up to $5 million. (The contention that the United States bought Florida for $5 million is erroneous.)

Approved by the Senate, the treaty encountered a hiccup when it arrived in Spain. An error was discovered in one treaty’s terms having to do with land grants the king made to various Spanish noblemen, and Spain tried to trade the lands back to the United States in exchange for putting pressure on the new Spanish American republics.

The treaty passed two years in limbo until a rebellion of Spanish army officers, who refused to continue fighting in the Americas, forced Fernando to acquiesce to the wishes of the Spanish legislature on, among other issues, accepting the treaty with the United States.

Approved in Spain, the treaty was again ratified by the Senate on February 22, 1821—exactly two years after Secretary Adams’ most important day.[10]

The full significance of the treaty emerged only later in the nineteenth century. It cleared the way for U.S. expansion south into Florida and west to the Pacific Ocean. In time, Americans pushed against the border in the west, putting more pressure on an independent Mexico.

The pushing turned to war in 1846, and after the United States took the provinces once contemplated as the limits of American growth, a vast expansion of territory lay bare the nation’s ugliest disagreement: what to do about slavery?

Adams knew the true results of his accomplishment would only be realized in the future.

“What the consequences may be of the compact this day signed with Spain is known only to the all-wise and all beneficent Disposer of events,” he recorded in his diary.

But despite the unknown, Adams was cautiously hopeful. “May no disappointment embitter the hope which this event warrants us in cherishing,” he wrote. “May its future influence on the destinies of my country be as extensive and as favorable as our warmest anticipations can paint!”[11]

David Head teaches history at the University of Central Florida. He is the author of Privateers of the Americas: Spanish American Privateering from the United States in the Early Republic and A Crisis of Peace: George Washington, the Newburgh Conspiracy, and the Fate of the American Revolution. For more information visit www.davidheadhistory or follow him on Twitter @davidheadphd.

Click Here to have the NEWEST essay in this study emailed to your inbox every day!

Click Here to view the schedule of topics in our 90-Day Study on American History.

[1] John Quincy Adams, February 22, 1819, Memoirs of John Quincy Adams, ed. Charles Francis Adams, 12 vols. (Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1874–77), 4: 274. https://books.google.com/books?id=kLQ4AQAAMAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&pg=PA274#v=onepage&q&f=false

[2] The text of the treaty can be found at https://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/sp1819.asp;

[3] For overviews of the treaty, its context, and its negotiation, see J. C. A. Stagg, Borderlines in Borderlands: James Madison and the Spanish–American Frontier, 1776–1821 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009); James E. Lewis, Jr., The American Union and the Problem of Neighborhood: The United States and the Collapse of the Spanish Empire, 1783–1829 (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1998); Samuel Flagg Bemis, John Quincy Adams and the Foundations of American Foreign Policy (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1969); Philip C. Brooks, Diplomacy in the Borderlands: The Adams–Onís Treaty of 1819 (1939; reprint, New York: Octagon, 1970).

[4] Adams, February 22, 1819, Memoirs, 4: 275. https://books.google.com/books?id=kLQ4AQAAMAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&pg=PA275#v=onepage&q&f=false

[5] The text of the Treaty of Paris can be found at https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/paris.asp.

[6] David Head, Privateers of the Americas: Spanish American Privateering from the United States in the Early Republic (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2015), 21–22.

[7] The Louisiana Purchase treaty can be found at https://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/louis1.asp; the Treat of San Ildefonso can be found at https://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/ildefens.asp.

[8] Head, Privateers, 21–22, 25–29.

[9] Adams, January 10, 1818, Memoirs, 4: 37. https://books.google.com/books?id=kLQ4AQAAMAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&pg=PA37#v=onepage&q&f=false

[10] Head, Privateers, 29–30.

[11] Adams, February 22, 1819, Memoirs, 4: 274. https://books.google.com/books?id=kLQ4AQAAMAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&pg=PA274#v=onepage&q&f=false

Trackbacks & Pingbacks

[…] didn’t stop with diplomatic and moral concessions, however. Constituting America notes that endless boundary debates with the newly-formed United States made the territory more […]

Join the discussion! Post your comments below.

Your feedback and insights are welcome.Feel free to contribute!