April 21, 1836: The Battle of San Jacinto, Mexico Surrenders and Texas is Freed

Remember the Alamo! The Battle of San Jacinto and Texan Independence

In December 1832, Sam Houston went to Texas. He had been a soldier, Indian fighter, state and national politician, and member of the Cherokee. Beset by several failures, he sought a better life in Texas. On the way, Houston traveled to the San Antonio settlement with frontiersman and land speculator, Jim Bowie, to San Antonio.

During the 1820s, thousands of Americans had moved to Texas in search of land and opportunity. The Mexican republic had recently won independence and welcomed the settlers to establish prosperous settlements under leaders such as Stephen F. Austin. These settlers were required to become Mexican citizens, convert to Catholicism, and free their slaves. The prosperous colony thrived, but Mexican authorities suspected the settlers maintained their American ideals and loyalties and banned further immigration and cracked down on the importation of slaves in 1830.

In 1833, Houston attended a convention of Texan leaders, who petitioned the Mexican government to grant them self-rule. Austin presented the petition at Mexico City where he was imprisoned indefinitely. Meanwhile, the new Mexican president, Antonio López de Santa Anna, took dictatorial powers and sent General Martin Perfecto de Cos to suppress Texan resistance. When Austin was finally released in August 1835, he asserted, “We must and ought to become part of the United States.”

Texans were prepared to fight for independence, and violence erupted in October 1835. When Mexican forces attempted to disarm Texans at Gonzales, volunteers rushed to the spot with cannons bearing the banner “Come and Take Them” and blasted them into Mexican ranks. Texans described it as their Battle of Lexington, and with it, the war for Texas independence began.

In the wake of the initial fighting, the Texans began to organize their militias to defend their rights with the revolutionary slogan “Liberty or Death!” Houston appealed to the Declaration of Independence and was an early supporter of an independent Texas joining the American Union.

Houston was appointed commander-in-chief of Texan forces. His fledgling army was a ragtag group of volunteers who were ill-disciplined and highly individualistic and democratic. His strategy was to avoid battle until he could raise a larger army to face the Mexican forces, but he could barely control his men. He opposed an attack on San Antonio, but his men launched one anyway. On December 5, Texans assaulted the town and the fortified mission at the Alamo. Texan sharpshooters and infantry closed in on General Cos’s army. Despite the arrival of reinforcements, Cos surrendered on the fourth day, and his army was permitted to march home with their weapons.

Santa Anna brought an army to San Antonio and besieged the Alamo held by 200 Texans under William Travis. The Texans deployed their men and cannons around the fort, and begged Houston for more troops. Travis pledged to fight to the last man. James Fannin launched an abortive relief expedition from Goliad, 100 miles away, but had to turn back for lack of supplies. The men at the Alamo were on their own, except for one recent American who came.

Davey Crockett was a colorful frontiersman and a member of Congress who said, “You can go to hell, I will go to Texas.” Crockett arrived in San Antonio in February and went to the Alamo. He proudly fought for liberty and roused the courage of the defenders.

Before dawn on March 6, the Mexican army assaulted the mission in four columns from different angles. The defenders slaughtered the enemy with cannon blasts but still they advanced. The Mexicans scaled ladders and were picked off by sharpshooters. Soon, the attackers established a foothold on the walls and overwhelmed the defenders. The Mexicans threw open the gates for their comrades, and the Texans and Crockett retreated into the chapel. They made a last stand until the door was knocked down and nearly all inside were killed.

Santa Anna made martyrs and heroes of the men who fought for Texan independence at the fort. “Remember the Alamo!” became a rallying cry that further unified the Texans. At Gonzales only a few days before, on March 2, the territory’s government had met in convention and declared Texas an independent republic in a statement modeled on the Declaration of Independence. The delegates appealed to the United States for diplomatic recognition and aid in the war.

Later that month, James Fannin’s garrison of about 400 men was trapped by the Mexican army. The Texans courageously repelled several cavalry charges and fought through the night until they ran low on water and ammunition. The following day, they were forced to surrender, and Mexican forces executing the unarmed prisoners by firing four volleys into their ranks. The atrocity led to another rallying cry: “Remember Goliad!”

Houston only had 400 soldiers remaining and refused to give battle. Santa Anna chased the Texan government from Gonzales and terrorized civilians throughout the area with impunity. However, hundreds of Texans enthusiastically flocked to Houston’s camp, and he learned that Santa Anna’s force had only 750 men. Houston moved his army to the confluence of the Buffalo Bayou and San Jacinto River, where he deployed his force in the woods.

On April 20 the two armies squared off and engaged in an artillery duel with the Texans firing their canons, nicknamed the “Twin Sisters.” A group of Texan cavalry sallied out and ignored an order only to scout enemy positions. The cavalry exchanged fire with the Mexicans and narrowly escaped back to their lines. Both sides retired and prepared for battle the following day.

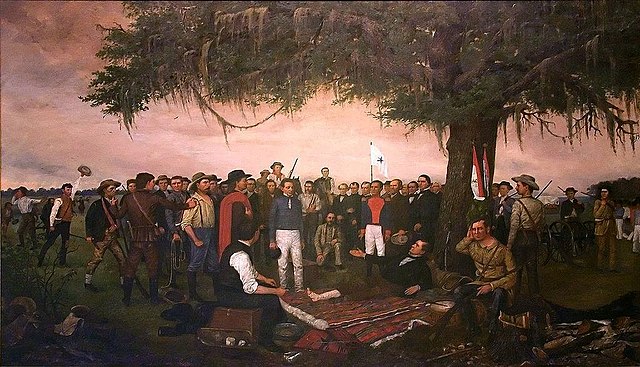

On the morning of April 21, General Cos arrived and doubled the size of Santa Anna’s army, but his men were exhausted from their march and took an afternoon nap. Houston seized the moment and formed up his army. They silently moved across the open ground until they started yelling “Remember the Alamo! Remember Goliad!” The shocked Mexican army roused itself and quickly formed up. The Texans’ “Twin Sisters” canons blasted away, and the infantry drove the Mexicans into the bayou while the cavalry flanked and surrounded them. In a little over 20 minutes, however, 630 were killed and more than 700 captured. Santa Anna was taken prisoner and agreed to Texan independence. The new republic selected Houston as its president and approved annexation by the United States.

Americans were deeply divided over the question of annexation, however, because it meant opening hostilities with Mexico. Moreover, many northerners, such as John Quincy Adams and abolitionists, warned that annexation would strengthen southern “slave power” because Texas would come into the Union as a massive slave state or several smaller ones. Eight years later, in 1844, President John Tyler supported a resolution for annexation after the Senate had defeated an annexation treaty. Both houses of Congress approved the resolution after a heated debate, and Tyler signed the bill in his last few days in office in early March 1845.

Annexation led to war with Mexico in 1846. Throughout the annexation debate and contention over the Mexican War, sectional tensions raised by the westward expansion of slavery tore at the fabric of the Union. The tensions eventually led to the Civil War.

Tony Williams is a Senior Fellow at the Bill of Rights Institute and is the author of six books including Washington and Hamilton: The Alliance that Forged America with Stephen Knott. He is currently writing a book on the Declaration of Independence.

Click Here to have the NEWEST essay in this study emailed to your inbox every day!

Click Here to view the schedule of topics in our 90-Day Study on American History.

Join the discussion! Post your comments below.

Your feedback and insights are welcome.Feel free to contribute!