Preventing Loss of Independence to Foreign or Global Governments by Upholding the Principle of America’s National Sovereignty

Essay Read by Constituting America Founder, Actress Janine Turner

Essay Read by Constituting America Founder, Actress Janine Turner

The previous essay, #17, showed that, according to the principles of the Declaration of Independence, the people of the United States of America have a right, from the “Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God,” to establish their independence and thereby their national sovereignty. Those same principles, however, that establish the right of a people to independence and sovereignty, also impose a duty upon government to protect and maintain that independence and sovereignty once established. This essay will focus further on the principle of America’s national sovereignty upon preventing loss of independence to foreign or global governments acting as with binding authority in attempts to undermine the United States.

The duty of government to maintain national sovereignty and political independence arises from two arguments of the Declaration of Independence regarding the very nature and purpose of government. First, the Declaration of Independence asserts that it is the equal right of every people, sharing the same political principles, to form through consent a government laid on such foundations “as to them shall seem most likely to affect their safety and happiness.” The Declaration of Independence also asserts that “governments are established among men” for the purpose of protecting the natural rights of its citizens. These principles therefore impose a duty upon our government, because independence is necessary in order for us as a people to determine what must be done for national security, which is, in turn, necessary in order for our citizens to peacefully enjoy their natural rights in the pursuit of happiness. A nation must maintain its independence, therefore, free from the political control of any other nation, in order to remain master of its own fortunes. Only when it has such liberty can a nation freely and prudently determine for itself what is necessary for the preservation, security, and happiness of its own people.

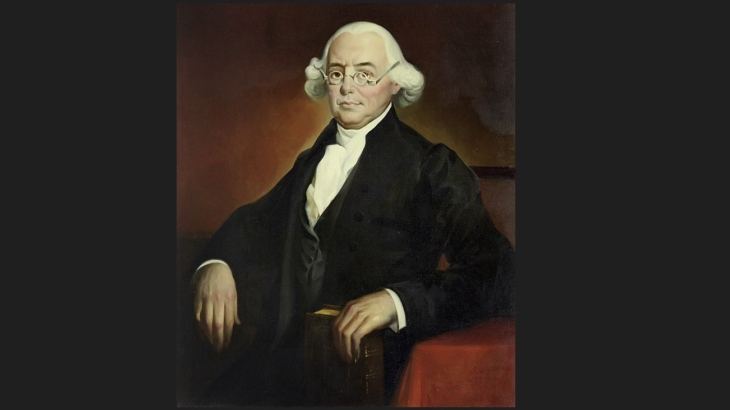

The importance of maintaining political independence can also be seen in the writings of American Founder James Wilson, signer of the Declaration of Independence, framer of the United States Constitution, and one of the original Supreme Court Justices appointed by President Washington. In his important work Lectures on Law, Wilson clearly echoed the Declaration of Independence on the right and duty of maintaining independence:

The law of nations, properly so called, is the law of states and sovereigns, obligatory upon them in the same manner, and for the same reasons, as the law of nature is obligatory upon individuals . . . The same principles, which evince the right of a nation to do everything, which it lawfully may, for the preservation of itself and of its members, evince its right, also, to avoid and prevent, as much as it lawfully may, everything which would load it with injuries, or threaten it with danger.[1]

The right and duty of the United States to defend its national sovereignty was also articulated by American courts well into the nineteenth century. In Schooner Exchange v. McFaddon (1812), for example, Chief Justice Marshall wrote that “[t]he world [is] composed of distinct sovereignties, possessing equal rights and equal independence.” In light of those equal rights, Marshall continued:

The jurisdiction of the nation within its own territory is necessarily exclusive and absolute. It is susceptible of no limitation not imposed by itself. Any restriction upon it, deriving validity from an external source, would imply a diminution of its sovereignty to the extent of the restriction, and an investment of that sovereignty to the same extent in that power which could impose such restriction. All exceptions, therefore, to the full and complete power of a nation within its own territories, must be traced up to the consent of the nation itself. They can flow from no other legitimate source. [2]

In its larger sense, political independence especially means the liberty that a people or nation has by right to decide when to engage in war or continue in peace. George Washington understood well that to have full freedom regarding such decisions, the United States should have as little political connection with other nations as possible, by which they might have an undue influence in determining what actions we might – or must – take. This especially meant that we should avoid as much as possible engaging in permanent political or military alliances with other nations – a lesson the United States learned through the controversy over the French Treaties during the French Revolution in the 1790s. During this time, Americans were passionately divided over whether the treaties with the French (agreed to by Congress during the American Revolution) obliged the United States to assist France in its wars against other European nations during the French Revolution. The issue nearly embroiled the United States in the French Revolution against its will and contrary to the desire of Congress.

Reflecting on this challenge to American political independence in his Farewell Address, Washington wrote, “The Nation which indulges towards another an habitual hatred, or an habitual fondness, is in some degree a slave. It is a slave to its animosity or to its affection, either of which is sufficient to lead it astray from its duty and its interest.” The peace and sometimes the liberty of nations, Washington wrote, had frequently been the victims of such foreign attachments. This is especially so when “the policy and will of one country, are subjected to the policy and will of another” through permanent alliances. Washington understood, therefore, that having “command of one’s own fortunes” could hardly apply to a slave any more than to a people who “interweave [their] destiny with that of any part of Europe, [or] entangle [their] peace and prosperity in the toils of European Ambition, Rivalship, Interest, Humour or Caprice.” Only when a people remains politically independent can it be free to select the means most conducive to its own safety and happiness; or, as Washington wrote, free to “choose peace or war, as our interest, guided by justice, shall counsel.”[3]

Christopher C. Burkett is Associate Professor of History and Political Science, and Director of the Ashbrook Scholar Program at Ashland University.

Christopher C. Burkett is Associate Professor of History and Political Science, and Director of the Ashbrook Scholar Program at Ashland University.

[1] James Wilson, Lectures on Law, in Collected Works of James Wilson, edited by Kermit L. Hall and Mark David Hall, Volume I (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2007), 529 and 536.

[2] Schooner Exchange v. McFaddon (7 Cranch 116 1812), The Founders’ Constitution, http://press-pubs.uchicago.edu/founders/documents/a1_8_10s7.html (accessed January 5, 2010)(emphasis added).

[3] Washington, Farewell Address, 1796.

Click here for First Principles of the American Founding 90-Day Study Schedule.

Click here to receive our Daily 90-Day Study Essay emailed directly to your inbox.

In #17, you noted that “the American Revolution was at its core an ideological movement that was motivated by a political philosophy shared in common not only by the prominent movers of events but by Americans in general. This philosophy is commonly referred to as social compact theory.” Do Americans today still share a common political philosophy?

America is in danger of losing our sovereignty, on a number of fronts. From illegal immigration,to membership in both W.H.I and the United nations, and the many treatys our nation engaged in. Our elected officials would do well to read this essay and the others in this series.