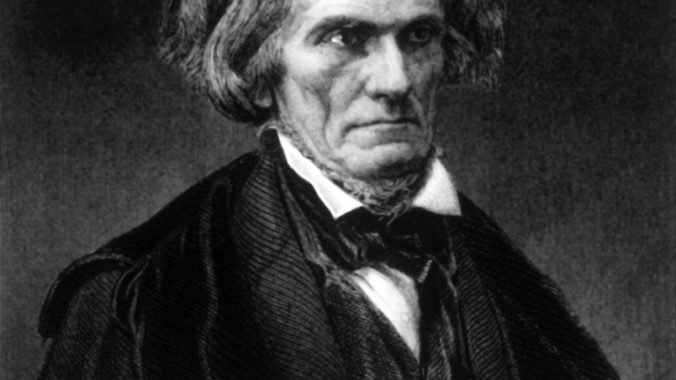

John C. Calhoun (1782-1850) – Seventh U.S. Vice President, South Carolina House & Senate Member

LISTEN ON SOUNDCLOUD:

For nearly the first half of the nineteenth century, three men dominated the debates over the great issues of the day. They were the “Great Triumvirate,” Henry Clay of Kentucky, Daniel Webster of Massachusetts, and John C. Calhoun of South Carolina. Each joined the Congress between 1806 and 1813, each served in the Cabinet as Secretary of State, and each indulged his ambition to become President in at least three campaigns. Clay came closest, with three party nominations. Calhoun, however, gained the highest honor. He served as Vice-President for nearly eight years with two different Presidents, John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson, one of only two men to do so.

John C. Calhoun was born on March 18, 1782, in the South Carolina Piedmont. After preliminary schooling, he attended Yale University, graduating in 1802. He spent the following year studying law at the then-preeminent law school in the United States, the pioneering Litchfield Academy of Judge Tapping Reeve in Connecticut. Upon returning to South Carolina, Calhoun practiced law in Charleston. As were several other Southern states, South Carolina was divided politically between east and west, the Tidewater and the Piedmont, with the former inclined towards Federalism and the latter towards Jeffersonian Republicanism. Because of political manipulation, the eastern minority controlled the state in its early years, and South Carolina had approved the Constitution by a 2-1 margin, despite the losing side representing a majority of the state’s population. Charleston was as Federalist and nationalist as any city in the North. However, times were changing. Within a generation, the state would become the leader of Southern sectionalism and, after another generation, the first to secede from the Union in 1860.

The state’s political and constitutional metamorphosis is reflected in Calhoun’s own philosophic journey. Yet, despite his well-earned reputation as a leading intellectual figure of the “South Carolina Doctrine” regarding the nature of the Union and the rights of the states, Calhoun always seemed to lag behind his state’s political evolution. He was never the firebrand driving the train of revolution, but always the brakeman seeking to slow it down. He was never a committed political partisan, instead wandering from faction to faction and party to party and best described as he saw himself, an independent for whom broader principles were a better guide than fleeting political association. That said, he also used this willing flexibility in political affiliation to maximize his personal standing and that of his state and section.

Calhoun was influenced by the Federalism of Yale’s president, Timothy Dwight, and of Judge Reeve. While it is difficult to assess the extent to which any particular intellectual mentor or personal experience affected Calhoun’s later views, it was there that he first heard systematic defense of the states’ rights doctrine. The Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions of 1798 against the Sedition Act clearly influenced his later doctrinal analysis. But those were events from his youth, whereas he lived the Federalism of his teachers who were reacting against the political revolution of the election of 1800 that saw Jefferson become President and consign the Federalist Party to a diminishing regional status.

Within a few years of his return to South Carolina, he was elected to the state legislature. In 1811 he entered the House of Representatives, where he became a “war hawk” who fervently backed the War of 1812 against Great Britain. That war saw the hardening of states’ rights views among the politically disaffected New England Federalists whose sea-faring and commercial communities were ravaged economically by the British naval blockade. Their politicians, including Daniel Webster, denounced the war and praised their states’ resistance to it. Eventually, their opposition coalesced into the Hartford Convention of 1814, which debated what forms of opposition states might undertake against unconstitutional federal laws. Secession, while not officially sanctioned, was put on the table for future discussion, should lesser measures fail. Calhoun and others later would use the Hartford Convention as a precedent to hurl at Northerners who attacked similar Southern sentiments.

In the meantime, chastened by the disastrous impact the war had on the financial stability of the country, Calhoun supported numerous measures that would have made Alexander Hamilton and other earlier Federalists proud. He introduced the bill to charter the Second Bank of the United States in 1816. He was a strong supporter of House Speaker Henry Clay’s “American System” of internal improvements directed by the federal government, which fit not only the South’s political alliance with the West, but also Calhoun’s (failed) dream to have South Carolina become a textile manufacturing center that would compete with Massachusetts. Most awkward for Calhoun and the South Carolinians for their anti-tariff posture a decade later, Calhoun led the move to enact the tariff of 1816 to pay off the government’s debts and reestablish solid public credit.

His political ambition was soon focused on executive office. Calhoun had been shocked by the generally poor performance of the militia during the War of 1812, as well as by what he perceived as the poor management of the War Department. In 1817, he began his tenure as Secretary of War, in which he supported a strong navy and, again in contrast to traditional republicans, a standing peace-time army. His success boosted his chances for the Presidency, and, in another ironic twist, a group of Northern congressmen placed his name in nomination for that office in 1821. He undertook a more concerted campaign in 1824, which was derailed in part because Southern support went to the more states’ rights oriented William Crawford of Georgia. Indeed, due to his perceived nationalism, Calhoun could not even get the support of his own state’s legislature, which, at that time, still selected presidential electors. Calhoun then turned his sights on the vice-presidency, and the Electoral College overwhelmingly selected him.

It was at that point that Calhoun’s determined nationalism began to give way over the next decade to an equally committed sectional loyalty. South Carolinians, who had suffered severely from the economic depression that followed the Panic of 1819, in increasingly radical sentiments opposed various tariffs enacted in the 1820s. Up-and-coming politicians such as Congressman George McDuffie and state representative Robert Barnwell Rhett (Calhoun’s successor as Senator in 1850 and the leader of what came to be known as the “Fire-Eaters”) campaigned not just for repeal of the tariffs, but for more active opposition to federal power.

The final blow was the massive “Tariff of Abominations” in 1828. Rebuked by other Southern states and unable to get a united front against the measure, South Carolina went on her own. Nullification became a respectable political topic. The most voluble among local politicians went further. Thus, Rhett, emulating Samuel Adams’s rhetoric during the struggle for independence from Britain, sounded the revolutionary clarion:

“But if you are doubtful of yourselves–if you are not prepared to follow up your principles wherever they may lead, to their very last consequence–if you love life better than honor,–prefer ease to perilous liberty and glory; awake not! Stir not!–Impotent resistance will add vengeance to your ruin. Live in smiling peace with your insatiable Oppressors, and die with the noble consolation that your submissive patience will survive triumphant your beggary and despair.”

Alarmed at such radicalism, Calhoun anonymously penned his Exposition and Protest against the Tariff of 1828, at the request of leaders of the state legislature. It accepted the constitutional power of the general government to enact tariffs to raise revenue–thereby glibly endorsing Calhoun’s support for the tariff of 1816–but not for protection of local industry. It further set down the basics of Calhoun’s theory of nullification, that a state retained its authority to veto unconstitutional federal laws. While the pamphlet’s authorship soon became known, Calhoun and the state’s senators, Robert Hayne and William Smith, publicly opposed or were non-committal about undertaking nullification. As a result, the movement stalled.

However, the radicals defeated the moderates in South Carolina’s elections in late 1830. Nullification leader James Hamilton was elected governor, and Smith was replaced by the more radical Stephen Miller. Calhoun, struggling to control the anti-tariff movement in the state, published his foundational Fort Hill Address on July 26, 1831. There, he systematically laid out the constitutional case for nullification. Calhoun acknowledged that within its delegated powers, properly exercised, the general government was immune from state interference. However, the same principle applied to the states’ reserved powers, reciprocally immune from ultra vires acts of the general government. The problem was what to do when a conflict arose.

An expert on constitutional law, and member of the Southwestern Law School faculty, Professor Joerg W. Knipprath has been interviewed by print and broadcast media on a number of related topics ranging from recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions to presidential succession. He has written opinion pieces and articles on business and securities law as well as constitutional issues, and has focused his more recent research on the effect of judicial review on the evolution of constitutional law. He has also spoken on business law and contemporary constitutional issues before professional and community forums, and serves as a Constituting America Fellow. Read more from Professor Knipprath at: http://www.tokenconservative.com/.

Click Here to have the NEWEST essay in this study emailed to your inbox every day at 12:30 pm Eastern!

Click Here for the previous essay.

Click Here for the next essay.

Click Here to view the schedule of topics in our 90 Day Study on Congress.

Join the discussion! Post your comments below.

Your feedback and insights are welcome.Feel free to contribute!