Direct Election And How The Number Of Constituents Per Congressional District Affects Representation

LISTEN ON SOUNDCLOUD:

Republican government operates through voting and representation. In a geographically large polity, physical distance makes direct voting by its citizens impractical. In a populous polity, direct voting by citizens likewise becomes impractical, as it is difficult for a significant number of them to engage in proposing and debating public measures, or, as was the case even in ancient Athens, to find a place for all to gather. In both scenarios, the principle of consent of the governed as the ethical basis of the government is eroded as popular participation diminishes. Political participation must then be channeled into electing representatives who will vote on the citizens’ behalf in the law-making assembly. Setting the qualifications of those entrusted with the vote and defining the basis of the representational system thus become crucial endeavors for the polity. The focus in this essay is on the nature of representation.

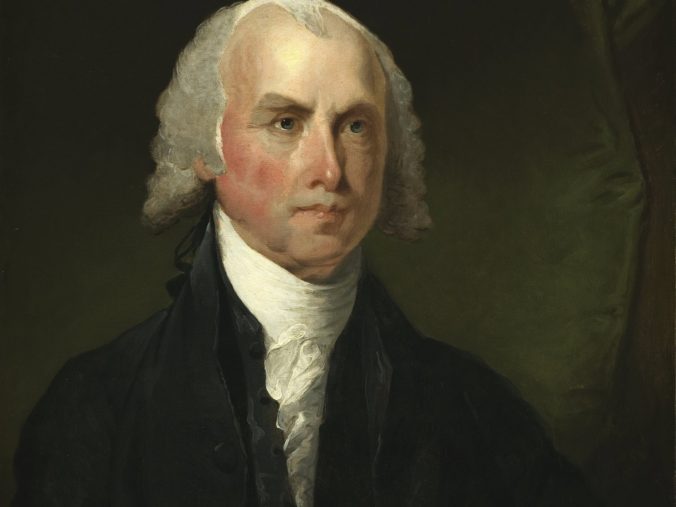

As the writers of The Federalist Papers explained, a representational system based on population must address two conflicting pressures. The population in the relevant districts must be sufficiently small that the representative realistically may be said to reflect the concerns of his constituents, yet not so small as to increase the size of the assembly to the point of functional ineffectiveness. As James Madison observed in Federalist 52, “[I]t is particularly essential that the [House of Representatives] should have an … intimate sympathy with, the people.” At the same time, he wrote four essays later, “The truth is, that in all cases, a certain number at least seems to be necessary to secure the benefits of free consultation and discussion; and to guard against too easy a combination for improper purposes: as on the other hand, the number ought at most to be kept within a certain limit, in order to avoid the confusion and intemperance of a multitude….Had every Athenian citizen been a Socrates, every Athenian assembly would still have been a mob.” The Philadelphia Convention set the original apportionment among states at no more than one seat in the House of Representatives for each 40,000 residents. On the last day of the Convention, that was decreased without debate to 30,000, a number that James Madison in Federalist 56 noted to be the ratio in the British House of Commons, as well.

The concern about districts that are too populous ties into the broader question of what constitutes a political “community.” That concern is not new. In his book The Laws, Plato put the ideal size at 5,040 citizens. Reflecting his Pythagorean fascination with numbers and mathematical precision, that size is the product of multiplying numbers 1 through 7 by each other. Since “citizens” did not include women, children, metics (aliens), and slaves, the actual population of such a community likely would be between 30,000 and 50,000, with 40,320 being Plato’s citizen number multiplied by 8. In what is unlikely to be coincidental, James Madison in Federalist 57 notes that House members would be elected by 5000 to 6000 citizens each. Aristotle was less precise. He opined that the polis had to be large enough to be self-sufficient, yet not so large that people did not know each other and order could not be maintained. Although Athenian citizens voted directly in the democratic assembly, the same measures of community would apply in a republican system of representation by districts. To exercise wise judgment in political matters, either as a voter or representative, it helps to know your fellow citizens personally and their concerns and interests. As Madison agreed in Federalist 56, “It is a sound and important principle, that the representative ought to be acquainted with the interests and circumstances of his constituents.”

With the large population of the United States, representation in the House is now based on districts that each have, on average, about three-fourths of a million residents, roughly the size of the largest state in the Union in 1790, Virginia. This departs grotesquely from the traditional understanding of community and calls into question how “republican” the system of governance in the United States is today. The vast majority of voters cannot personally get to know the candidates, or they the voters. Voters cannot gage accurately the general community concerns and interests, as they cannot interact extensively with a sufficient number of their fellow-residents. Campaign flyers the month before the election, occasional forums before necessarily limited numbers of constituents, and, from only a few representatives, a brief message or constituent survey once or twice a year cannot establish the requisite relationship for truly republican self-government. Much “debate” of issues occurs either through mass distribution of brief collections of grossly distorted “facts” in campaign literature, unverifiable claims in “robocalls,” and maudlin appeals to emotions in televised ads, or through the musings of “talking heads” colored by personal ideology or financial interest. As a result, voter confusion and ignorance increases. Many are turned off by the process and, from this alienation, voter participation decreases. That, then, empties “consent of the governed” of its practical content and threatens to make it an entirely theoretical construct to hide the actions of an oligarchic government of the elite, by the elite, and for the elite.

Two factors might counteract the threat that populous districts pose to the republican principle of representation. One is the technological revolution that allows participation via one’s computer in virtual “town halls” with candidates and in debates among constituents through blogs or other websites. The second is that matters of national importance such as war, foreign relations, interstate commerce, immigration, and a sound currency affect all Americans. Therefore, there is less salience to the idea that a representative need be clearly cognizant of the particular sentiments of his district’s inhabitants.

As to the first, Madison addressed in Federalist 10 how the small number and physical proximity of local populations facilitates communication of ideas and conformity of interests. While he certainly did not consider this an unmixed blessing in either a democratic assembly or a legislative body, he accepted it as a traditional aspect of self-rule. However, the sheer number of potential participants and the necessarily limited time and frequency of virtual “town halls” still makes connection on a personal level among participants and with their representative unlikely.

Other versions of electronic communication have led to “virtual communities” that form apart from physical domiciles. There are several problems here. Those communities often are national, if not international. Their interests and concerns, and those of the blogger, may not reflect those of the district that elects the representative. Moreover, experience tells us that much debate on those blogs by commenters involves irrelevancies and digressions, as well as invective that, were it delivered in person rather than through the safety and anonymity of the computer keyboard in an undisclosed location, would be strongly curtailed. Such distractions would be much less likely to be tolerated in a physical meeting. The absence of an enforced agenda and the lack of civil discourse in such settings again alienates many, who then choose not to participate. Finally, there are intangible aspects to physical interactions that facilitate personal bonds and resolution of problems. Those aspects are lacking when discussion occurs through disconnected remarks among an atomized group of physically isolated commenters.

As to the second, the immediately obvious problem is that Congress no longer limits its legislation to truly national issues. Instead, the expansion of Congress’s substantive powers regarding interstate commerce, taxation, and spending, approved in Supreme Court opinions, brings personal decisions and policies that have predominantly local effect within Congress’s reach. For such issues, the particular needs and interests of local minorities are more likely to go unrepresented in larger, more homogenized districts. This is especially true since the Supreme Court has held that any population inequality in a state’s congressional districts will be closely scrutinized, thereby making it more difficult to adjust district boundaries to give such minorities a voice. As well, the problem of very large populations within legislative districts applies to many state and local bodies who are not dealing with national issues, but whose policies also are increasingly restrictive against personal actions. While it is admittedly an outlier, the five-member Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors makes policy that potentially affects over 10 million residents. California State Senate districts have about a million residents apiece; each Assembly district has a half-million, larger than all but one state in 1790. Some states and most localities have smaller districts, but other populous states’ legislatures operate similarly.

Another aspect of republican doctrine about representation is the requirement that two legislative chambers must concur in legislation. Bicameralism is not an essential republican feature, but it is nevertheless common. Such division serves to control the passions and self-interest of the general citizenry and, therefore, of their representatives, that is, “the propensity of all single and numerous assemblies, to yield to the impulse of sudden and violent passions, and to be seduced by factious leaders into intemperate and pernicious resolutions,” per Madison in Federalist 62. The typical form is that the “lower” chamber represents the interests of the numerically predominant social or economic class, and the “upper” house represents a different class, usually deemed wiser and more dispassionate in its deliberations for the common good.

There have been many forms of bicameralism. Even the ancient Athenian democracy did not place unrestricted power in the citizenry gathered in the popular Assembly. There was a Council of 500, apportioned equally among ten districts, whose members were chosen by lot (akin to a jury system). Each month of the ten-month “Conciliar Calendar” year, a district’s members would compose the 50-member steering committee that controlled the legislative agenda of the Assembly, especially in financial matters. In the Roman Republic, power was divided between the patrician Senate of the landed aristocracy and various assemblies of the plebeians. Those assemblies were further divided among six plebeian classes based on their wealth. That division maximized the power of the knights (“equites”), the wealthiest of the commoners, and minimized the influence of the poor.

Such wealth-based or status-based division has been a common form of bicameralism. When Britain controlled the American colonies, Parliament was composed of the House of Lords, whose members were certain high-level clergy of the Church of England (“Lords Spiritual”) and the hereditary landed high nobility (“Lords Temporal”), and the House of Commons, which represented the gentry and commercial classes. In the early United States, the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780 specified that males meeting a set property qualification could vote. However, the two houses of the General Court (legislature) were based on different political principles and had different qualifications for the members. The state’s House of Representatives was apportioned on the basis of population (actually, qualified voters) in incorporated towns. The Senate was apportioned among districts based on their wealth, as measured by the taxes collected from that district. The members of the House had property qualifications significantly higher than the voters, and the members of the Senate had property qualifications twice as high as those for the House. Such tiered property qualifications were not uncommon for voters and representatives in state legislatures for several decades after independence. As well, distinct methods of apportionment between the chambers of the legislature, as in the Massachusetts model, were common.

The Articles of Confederation provided for only a single chamber, and representation was based on the equal status of the States as constituent members. When the Framers drafted the Constitution, the Great Compromise of 1787 resulted in a House of Representatives primarily based on population and a Senate based on the same principle of state equality as under the Articles. The division was not formally class-based. Instead, it reflected a practical accommodation of political minorities in a large and diverse political entity whose residents’ primary identity was with their local communities. From another perspective, the smaller number of Senators and their longer terms would provide the necessary independence from fleeting popular passions and foster the reflection and wisdom to restrain the feared reflexiveness and tempestuousness of the House. There were no property qualifications specified for legislators, so that the broadest pool of talent was available. As the Supreme Court found in Powell v. McCormack (1969), the Framers did not intend that Congress could add qualifications to age, citizenship, and state residency explicitly provided in the Constitution. In 1995, in U.S. Term Limits v. Thornton, the Court held, with less historical justification, that states were likewise restricted. Property qualifications for voters were left to the discretion of each state, as long as qualifications were not more restrictive than those the state had for voters for the lower house of its own legislature. By the mid-1960s, however, the Twenty-Fourth Amendment and the Supreme Court’s decision in Harper v. Virginia Board of Elections (1966) made it unlikely that any wealth-based restriction on voting was constitutional.

In 1913, the Seventeenth Amendment changed the method by which Senators were chosen. Henceforth, they would be elected directly by voters. Recent critics have called for repeal of that amendment, because they view it as having caused the decline of the states’ political influence relative to the general government. However, the change from the original method of selecting Senators was the product of a long trend, not a sudden upheaval. A proposal to amend the Constitution to provide for popular election of Senators was introduced as early as 1826. For a couple of decades before the Seventeenth Amendment was adopted, states had been moving to allow “preference elections” by the people that would recommend to the legislature the person to be selected, thereby putting political pressure on legislators to select the winner.

It is unlikely that such a repeal movement would succeed, given the current culture of activist government and the political inertia in favor of constantly expanding the totality of voters. It is also doubtful that the power of the federal government would be reduced, even if the movement were successful. It requires suspension of disbelief to think that the California legislature, whose members are increasingly drawn from the Democratic Party’s most radical factions, is suddenly going to select Senators who favor turning off the federal spigot of funds, combatting illegal immigration, or supporting a person’s right to bear arms. Politics is downstream from culture, and the majority of people favors getting government-directed largesse paid for by others. The problem for republicanism, in other words, is with the voters, not with the representatives they elect.

An expert on constitutional law, and member of the Southwestern Law School faculty, Professor Joerg W. Knipprath has been interviewed by print and broadcast media on a number of related topics ranging from recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions to presidential succession. He has written opinion pieces and articles on business and securities law as well as constitutional issues, and has focused his more recent research on the effect of judicial review on the evolution of constitutional law. He has also spoken on business law and contemporary constitutional issues before professional and community forums,and serves as a Constituting America Fellow. Read more from Professor Knipprath at:http://www.tokenconservative.com/.

Click Here to have the NEWEST essay in this study emailed to your inbox every day at 12:30 pm Eastern!

Click Here for the previous essay.

Click Here for the next essay.

Click Here to view the schedule of topics in our 90 Day Study on Congress.

Join the discussion! Post your comments below.

Your feedback and insights are welcome.Feel free to contribute!