Essay Read by Constituting America Founder, Actress Janine Turner

From the beginning of our nation’s founding, the concept that all are equal under the law and have equal justice under law has been aspirational. But in the late 1890s, with the Supreme Court of the United States’ Fourteenth Amendment jurisprudence, the concept became concrete. Questions remain about whether the concept has been fully fulfilled.

The Idea

The concept of equal under the law is pretty straightforward. It means that regardless of race or color, political views, sex, religion, or other characteristics, justice is blind and everyone is treated the same and equally under the law. From the most powerful to the penniless, all are to be treated equally under the law, from due process rights to the rights under the Fourth and Fifth Amendments. A mental image of the concept can be had by taking a look at statues of Lady Justice, who has balanced scales before her and a blindfold over her eyes, so that impartiality is the standard by which all under the law are judged.

The Fourteenth Amendment

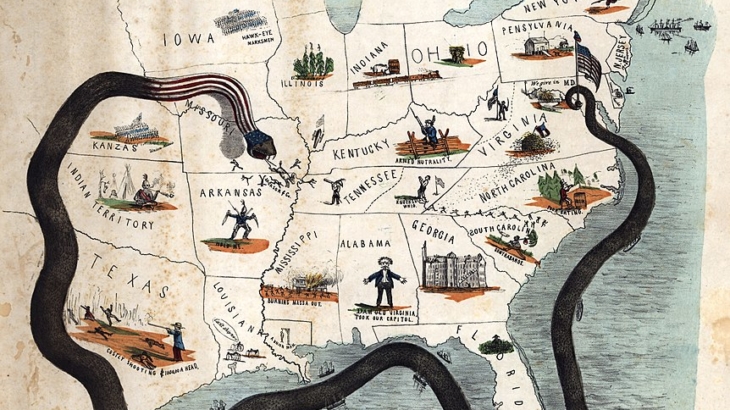

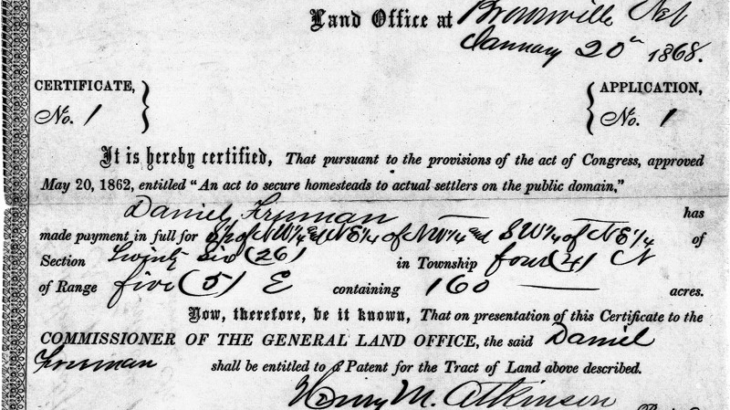

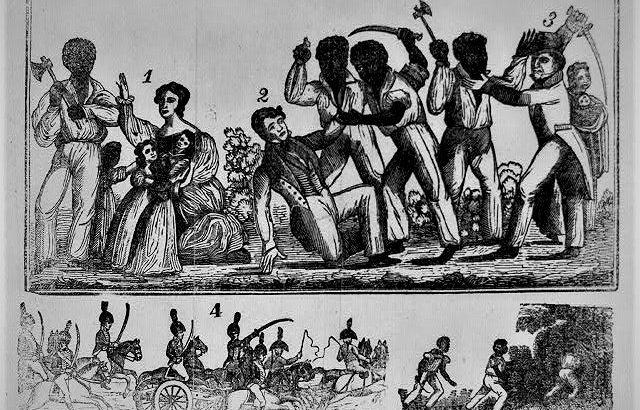

Some have referred to the passage of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments as the “Second Founding.” The Fourteenth Amendment language provides for equal protection, Section 1 ending, “nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” Blacks were the intended beneficiaries of the language, but in its early days after ratification, the Equal Protection Clause was not always used to benefit the intended beneficiaries.

The Language of Equal Justice Under Law

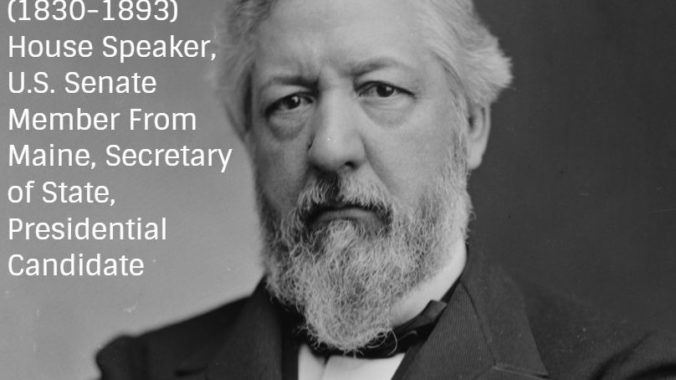

In 1891, in a case, Caldwell v. Texas, 137 U.S. 692 (1891), Chief Justice Melville Fuller wrote in a Fourteenth Amendment case (emphasis added), “By the Fourteenth Amendment, the powers of the states in dealing with crime within their borders are not limited, but no state can deprive particular persons or classes of persons of equal and impartial justice under the law.” In a second case, Leeper v. Texas, 139 U.S. 462 (1891), the Fuller Court repeated the same language. (The Fuller Court in 1896 in the context of segregation also gave us the language “separate but equal” in Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896).)

In 1958, in Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958), a post-Brown case involving the State of Arkansas and resistance to integration of public schools, the Court in an unsigned opinion wrote:

“The Constitution created a government dedicated to equal justice under law. The Fourteenth Amendment embodied and emphasized that ideal.”

The United States Constitution itself makes no mention, except for the Equal Protection Clause, of any equality concept.

The Pledge of Allegiance

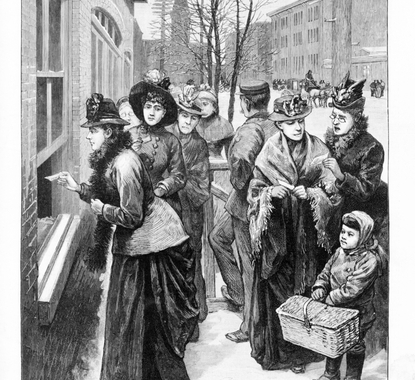

The concept of equality is embedded in many of our national documents, including the Pledge of Allegiance, which was written in 1892 (around the time of the Texas cases referenced above. The original Pledge read, “I pledge allegiance to my Flag and the Republic for which it stands, one nation, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.” The words “under God” were added in 1954, during the Red Scare, by President Dwight Eisenhower.

The Supreme Court Building

Prior to the 1930s, the Supreme Court met in the Senate building, with no separate home. Former President William Howard Taft, who became Chief Justice of the United States, worked to establish a place for the Court. Architects suggested the front of the building, the West Pediment, have the phrase, “Equal Justice Under Law,” over the entrance, to remind all that when they stepped before the highest court of the nation, they each were treated with equality. From the beginning, some have debated the phrase and whether the nine justices inside the building have lived up to the aspirational goal.

Roots Go Way Back

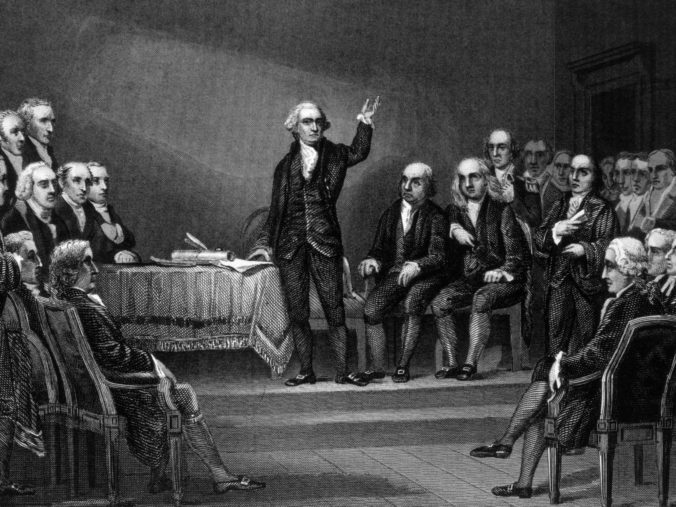

Democratic principles have long included notions of equality under the law. For example, in ancient Greece, Pericles wrote of equal justice under law.

From the United States of America perspective, our initial document establishing this Union, the Declaration of Independence, which we recently celebrated, begins in substance with the concept of equality:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

Conclusion

The debate about the law and whether all are treated “equal under the law” remains one of great interest and discussion. Our nation should be one that treats all equally under the law, and may this continue to be a goal we aspire to achieve.

Dan Cotter is Attorney and Counselor at Howard & Howard Attorneys PLLC. He is the author of The Chief Justices, (published April 2019, Twelve Tables Press). He is also a past president of The Chicago Bar Association. The article contains his opinions and is not to be attributed to anyone else.

Dan Cotter is Attorney and Counselor at Howard & Howard Attorneys PLLC. He is the author of The Chief Justices, (published April 2019, Twelve Tables Press). He is also a past president of The Chicago Bar Association. The article contains his opinions and is not to be attributed to anyone else.

Click here for First Principles of the American Founding 90-Day Study Schedule.

Click here to receive our Daily 90-Day Study Essay emailed directly to your inbox.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Venetian_Arsenal#/media/File:Campo_de_l'Arsenal.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Venetian_Arsenal#/media/File:Campo_de_l'Arsenal.jpg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_Republic#/media/File:Q._Servilius_Caepio_(M._Junius)_Brutus,_denarius,_54_BC,_RRC_433-1_reverse.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_Republic#/media/File:Q._Servilius_Caepio_(M._Junius)_Brutus,_denarius,_54_BC,_RRC_433-1_reverse.jpg