Beginnings Of The United States Congress – Guest Essayist: Tony Williams

LISTEN ON SOUNDCLOUD:

The Constitutional First Congress

As Representative James Madison reflected on the task of the First Congress, he stated, “We are in a wilderness without a single footstep to guide us.” Perhaps Madison was wrong for the representatives and senators had a few guides at their disposal. They had their experience in the state legislatures and the national Congress under the Articles of Confederation. In addition, they had their wisdom and prudence to pursue the public good in deliberative government. Most fundamentally, they had the new Constitution as the fundamental guide for all their actions.

The foremost task of the First Congress was to breathe life into the new government based upon constitutional powers and standards. In early April 1789, Congress finally assembled a quorum and immediately debated the necessary task of finding a means of collecting revenue for the federal government under the powers of Article I, section 8 and focused on tariffs, or a tax on imports. The debate immediately revealed a sectional split over protective tariffs, which were eventually passed over the objections of many southerners, and helped lay the foundation for a partisan divide.

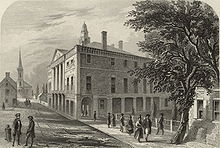

On April 30, President George Washington took his constitutional Oath of Office at Federal Hall and then delivered his First Inaugural Address to the Congress assembled in the Senate chamber. The Congress resolved several issues related to the presidency that summer.

First, a lengthy debate occurred in which Vice-President John Adams offered several suggested ways for addressing the president by titles that smacked of monarchism and earned him the sobriquet of “His Rotundity.” Congress wisely settled on the republican simplicity of “President of the United States.”

Second, President Washington actually went to the Senate for advice and consent on a proposed treaty with the Creek Indians because the Constitution seemed to mandate this course of action. After enduring frustrating haggling, Washington stormed out of the Senate and did not return, submitting future treaties for Senate ratification after they were made.

Third, Congress created several executive departments constituting a cabinet made up of the war department under Henry Knox, the treasury department under Alexander Hamilton (despite the great fear of corruption in this office), and the state department under a surprised Thomas Jefferson, who did not learn of his appointment until arriving back from France in late November and did not assume his duties until March 1790. The president won the authority over removal of the department officials. Virginian Edmund Randolph became the nation’s first Attorney General. To give some idea of the size of the federal government, Washington’s Mount Vernon had about the same number of people including workers and slaves.

The Congress had the constitutional authority under Article III to set up the federal court system including the Supreme Court. The resulting Judiciary Act of 1789 passed later that summer, and John Jay became the nation’s first chief justice of the Supreme Court.

On June 8, Madison rose on the floor of the House to deliver a speech proposing amendments for a Bill of Rights to fulfill the Federalist promise made during the ratification debate. While many representatives thought it was a “tub to the whale,” or a distraction from more important business, Madison persevered and eventually won passage of twelve amendments that were sent to the states for ratification. As a result, North Carolina and Rhode Island joined the Union.

While sectional fissures had opened up during the session that adjourned for the fall, Washington was pleased by the results: “It was indeed next to a miracle that there should have been so much unanimity, in points of such importance….So far as we have gone with the new government, we have had greater reason than the most sanguine could expect to be satisfied with its success.”

That fall, Secretary of Treasury Hamilton wrote a Report on Public Credit that he presented to the next session of the First Congress in early January. The controversial plan proposed for the national government to assume the massive war debts of the states to reorganize and pay the debt to place national finances on a firmer footing. The plan struck many in the South as an attempt to consolidate national power and stalled. Eventually, the plan passed that summer as part of a deal (the Compromise of 1790) for a national capital on the shores of the Potomac supposedly made at a famous dinner hosted by Jefferson for Madison and Hamilton.

Southerners were further outraged when a Quaker petition to end the slave trade (and thus slavery) was sent to the Congress. The ensuing debate over slavery took on a strong sectional cast right at the beginning of the nation and would plague national politics for the next seventy years.

The last session of the First Congress opened on December 1790 to no less controversy. At the behest of Congress, Secretary Hamilton submitted another financial plan, this one proposing a National Bank. This proposal again stirred up fears of centralization and stoked sectional tensions. When Madison and Jefferson raised objections, President Washington solicited opinions from his cabinet on the constitutionality of the bank because of his strict adherence to the Constitution. Hamilton’s arguments won the day and persuaded Washington to sign the bill passed by both houses of Congress. Whatever the divide and different views of each side, all the congressional and executive debates over the bank were anchored in the meaning and authority of the Constitution.

The First Congress had its share of divisive, mostly sectional politics that would form the basis of the nation’s first political parties only a few years after. However, the First Congress produced a series of remarkable legislative achievements that contributed to the political and economic stability of the new nation. Even when the members of Congress disagreed, the standard for their viewpoints and deliberations was the U.S. Constitution.

Tony Williams is Senior Teaching Fellow at the Bill of Rights Institute; a Constituting America Fellow; author of Washington and Hamilton: The Alliance that Forged America, and Hamilton: An American Biography.

Click Here for the previous essay.

Click Here for the next essay.

Click Here to view the schedule of topics in our 90 Day Study on Congress.

The first Congress worked together.. Congress today would benefit from reading today’s essay..

Thank you Barb! Great point! Please keep sharing on your social media!

Our problem today is that the Congress allows administrative law to replace Constitutional law. The original Congress used Constitutional, common law.

With no guide other than the Constitution, legislators then had to look to the Constitution to determine what limited powers all branches of the federal government had, and they seemed to strive to keep those powers limited. Today, as noted in the first two days’ essays, our citizens expect national legislators, agencies, and homeland security officials to solve all our local problems and our national legislators are too happy to oblige.

Thank you for the essay and the replies.

Madison was originally in the camp that believed that Constitution did not need a BoRights. But the Virginia State ratifying convention had such a vigorous debate, lead by Patrick Henry and other Founders, about the lack thereof that he was convinced that a BoRs was needed. So much so that he frustrated other Representatives who wanted to get on with forming a new government because he would not consent to taking it up later.